Does Nato have the political will to face up to Russia?

- Published

These protesters at the summit are seeking Nato's help

Nato has rarely escaped the existential question in the years since 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Now events in Ukraine, and accompanying statements from the Kremlin about acting to protect the interests of Russians in neighbouring countries, appear to offer a lifeline to the Western alliance - a "back to the future" mission organising collective defence against the threat of future coercion from the east.

It doesn't have to be complicated and it doesn't have to involve the alliance in new wars.

Simplicity

Indeed it can be argued that the whole strength of Nato during decades of Cold War lay in the simplicity of its mission and success of deterrence in avoiding actual conflict.

The organisation's founding charter, signed in Washington DC in 1949, is remarkable for its brevity.

Its key provision, Article 5, states that "an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all".

Other protesters want an end to Nato expansion

In a joint Times newspaper article on Thursday, David Cameron and Barack Obama wrote that now is the time to make "clear to Russia that we will always uphold our Article 5 commitments to collective self-defence".

Those running the Nato summit in Newport believe that they can use this moment, and the disquiet caused by recent events in the Ukraine, to press members to reverse the dismantling of their defences that has been going on for the past two decades.

They also want to get forces together that might go to the help of the three Baltic states that joined Nato at the end of the Cold War, and are now a prime focus for concern in the light of President Vladimir Putin's avowed irredentist policies.

Nuclear threat

There are a few reasons though why it might not be possible for the western allies to do this.

In the first place, there are some basic questions of political will.

Remarks by President Putin that others shouldn't "mess with" Russia over Ukraine and should remember that Russia was a significant nuclear power have escalated the rhetoric surrounding the crisis to a point where most western politicians would fear to tread.

The crisis in Ukraine will be dominating the agenda

A recent article by Russian strategist Andrey Piontkovsky caused shock in many European capitals, positing that Mr Putin's aims were "the maximum extension of the Russian world, the destruction of Nato, and the discrediting and humiliation of the US".

It added that Nato countries such as the US and Germany would not stand by the Baltic republics, and that, if necessary, the Kremlin would carry out a limited nuclear strike in Europe in order to break apart the two sides of the Atlantic alliance.

While Mr Piontkovsky was not writing in any official role - far from it - his pronouncements were considered a sufficiently accurate assessment of some of the more extreme thinking in the Kremlin that other people were writing in similar terms.

Warsaw practice

Anne Applebaum, a historian and columnist who is married to the Polish foreign minister, noted in the Washington Post that ideas of "de-coupling" Europe and America by a nuclear strike might be terrifying but they were hardly fantasy.

"In military exercises in 2009 and 2013, the Russian army openly practised a nuclear attack on Warsaw," she wrote.

Nobody in Nato thinks that the alliance should be going to Ukraine's defence with military force - it isn't a member of the bloc after all.

But the readiness of Russia to escalate, in practical terms by sending its forces into that country, or in rhetorical ones by mentioning nuclear weapons, have shocked many countries to the point where there is no consensus within Nato even about sending arms to Ukraine.

Obama and Cameron stressed their commitment to Article 5

Rather than seeing the new crisis in eastern Europe as a rallying call for new commitments to collective defence, many Nato members remain trapped in the mentality of the past decade's "contingency operations" involving "coalitions of the willing" in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The basis upon which these have been mounted - send forces if that's politically and militarily convenient for you - is fundamentally different to Nato's Cold War philosophy.

The reluctance of alliance members to return to that type of collective defence mentality can be seen in the reaction forces announced this week.

Defence cuts

Both the rapid action plan, and the joint expeditionary force are billed as ways in which Nato might mobilise troops to go to the aid of members such as the Baltic states if they felt they were coming under pressure from Russia.

But these forces, as currently constituted, involve contingents from a small number of willing nations.

The summit is taking place at Celtic Manor Resort

They do not bind together all Nato's big players - the US, UK, Germany, and Italy for example - in the way that the alliance's now defunct Cold War fire brigade, the Allied Command Europe Mobile Force did.

Of course the ability of members to take part in such ventures is constrained in part by the defence cuts that they have enacted over the past decade.

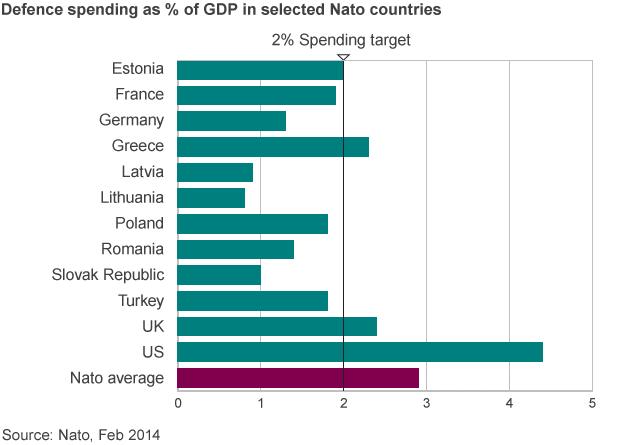

Not only have 24 of Nato's 28 members cut military spending below the 2% of GDP target that they have all (in theory) committed to uphold, but the cutting has gone on despite the Middle East and Ukraine crises of the past couple of years.

Figures published last week by Jane's showed that European countries had diverted $93bn (£57bn) from defence spending during 2012 to 2014 alone.

Actions not words

As hosts of this summit, Downing Street has been working to shepherd Nato members towards spending more on defence again.

But although the UK is one of those four countries (along with the US, Greece and Estonia) that still meet the 2% spending target, there are many unanswered questions about whether this country is prepared to increase its budget or will, on the contrary, make further cuts to its forces in next year's defence review.

As ever, the proof of the success or failure of this summit will be seen in the actions of participants rather than in the words of its communiqué.

But when even these are being constrained by the nervousness of member states to commit on paper to higher spending, helping Ukraine, or joint action on the Middle East, it's only fair to surmise that Nato is still a long way from re-discovering its Cold War sense of purpose.

- Published4 September 2014

- Published4 September 2014

- Published3 September 2014

- Published3 September 2014