Querying Nato's rapid reaction force

- Published

Russia's tactics in eastern Ukraine sparked soul-searching in Nato

Nato's political leaders have given the go-ahead for a fundamental re-casting of Nato's rapid reaction forces to bolster deterrence and reassure worried member states.

The alliance's new Readiness Action Plan contains a variety of measures to overhaul the reaction forces. The aim is to make sure that they can be well-equipped, highly trained and rapidly mobile.

The goal is to make good on Nato Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen's assertion at the Wales summit that "Nato protects all its allies at all times".

The message to any aggressor, he noted, was clear: "Should you even think of attacking one ally, you will be facing the whole alliance."

Of course, the essence of deterrence is not just capability but credibility. Nato's military chief in Europe, Gen Sir Adrian Bradshaw, said the overhaul of the response forces would mean taking a fundamental look at "the mechanisms by which this force is generated, trained and projected".

The current Nato Response Force is designed as a multinational organisation made up of land, air, maritime and Special Operations Forces. It is made up of three parts: A Nato command or headquarters element; a joint force of around 13,000 contributed by allies; and a pool of additional units to reinforce where necessary.

Nato explained in 80 seconds

The intention is to make one small part of this force even more rapidly deployable. It is being described as "a very high readiness spearhead" - some 4,000 strong - that could move eastwards say to Poland or north to the Baltic Republics within 48 hours.

Britain looks set to contribute a battle group to the land element of the force - say about 1,000-men - together with a brigade headquarters.

But nearly all the details must now be worked out. What should be the exact shape of the force and its capabilities? What about the vital enabling elements - logistics, communications and so on - that are required to get it into the field?

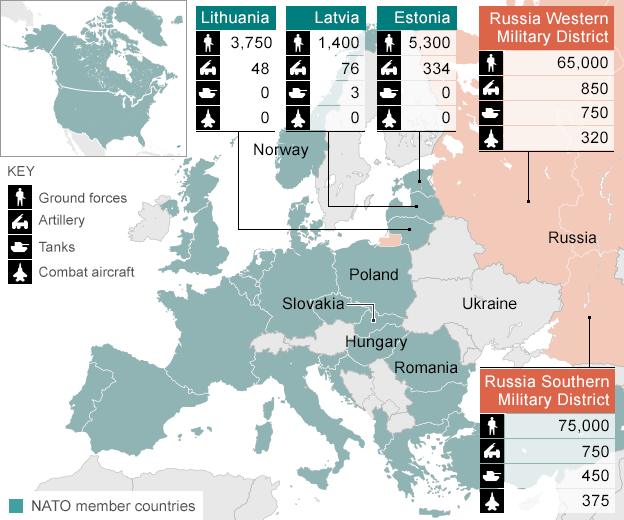

Source: IISS data and estimates

Then there is the vital question of what is called host-nation support. The spearhead's likely areas of deployment will also have to be studied. Does the infrastructure there enable rapid reinforcement? What bases might need to be enhanced or expanded? What equipment and supplies may need to be positioned ready for the reinforcing units when they arrive?

This new eastward thrust may require a new overall headquarters so that arriving units can be slotted into an existing strategic environment. Studies are under way to see if the new Multinational Corps North East headquarters needs to take on a specific role focusing on threats to Nato territory.

Watch: Timeline summary of the Ukraine conflict

Nato also has to look at other enhancements and improvements as to how it does business. Intelligence needs to be improved. There needs to be a better understanding about what is going on in countries on Nato's borders. In military terms, as Gen Bradshaw put it, there has to be a clearer sense of the "indicators and warnings that might trigger a defensive deployment".

There is going to be a greatly enhanced exercise programme with regular manoeuvres to train and demonstrate the new spearhead force's capacities.

This, says Gen Bradshaw, should enhance deterrence. You demonstrate capability "so that you don't have to get involved in a conflict."

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko held talks with Nato leader Anders Fogh Rasmussen at the summit

The UK and US are among only four Nato nations that meet the new spending commitments

Some analysts have described Russia's seizure of the Crimea and its alleged incursions into eastern Ukraine as a new kind of warfare - "hybrid" or "ambiguous" warfare. This is the use of conventional military build-ups and activities like subversion, agitation, political demonstration, along with a newer element - cyber attacks.

The whole purpose is to confuse the outside world.

Apart perhaps from the cyber element, much of this is not really all that new. Gen Bradshaw acknowledged that strategy has always been about combining all elements of government power. But it is clear that in a conflict that has been waged almost as much in the international media as it has on the ground, perceptions - and the managing (some would say manipulation) of perceptions - matter.

Better intelligence, concerted cyber defences and a greater rapidity of response are clearly three things intended to combat this "fog of hybrid war".

The Isaf mission in Afghanistan has been one of Nato's biggest undertakings

However, Nato's plans prompt many questions. For one thing they require more money.

Will the burden be equally shared? The Wales Summit communique speaks of those countries (24 out of 28 Nato members) who spend less than 2% of GDP on defence aiming "to move towards the 2% guideline within a decade".

In the past, brave budgetary words have rarely meant much in practice. Maybe the resurgent Russian threat, such as it is, will concentrate minds.

There are also big questions for some of Nato's key members as well, not least Britain. It plans to take a prominent role in the new spearhead force. It has also announced that it will establish a joint expeditionary force with a number of other allies.

Then there is also the joint Franco-British expeditionary force that is already being established.

But money is tight and new equipment is needed, not least because of the ravages of war in Iraq and then Afghanistan. Britain is one of the few Nato countries that does spend 2% of its GDP on defence, but respected UK think-tank Rusi has raised questions about whether Britain will be able to continue doing so.