Sweden Democrats tap into immigration fears

- Published

Jimmie Akesson rejects Sweden's liberal consensus politics

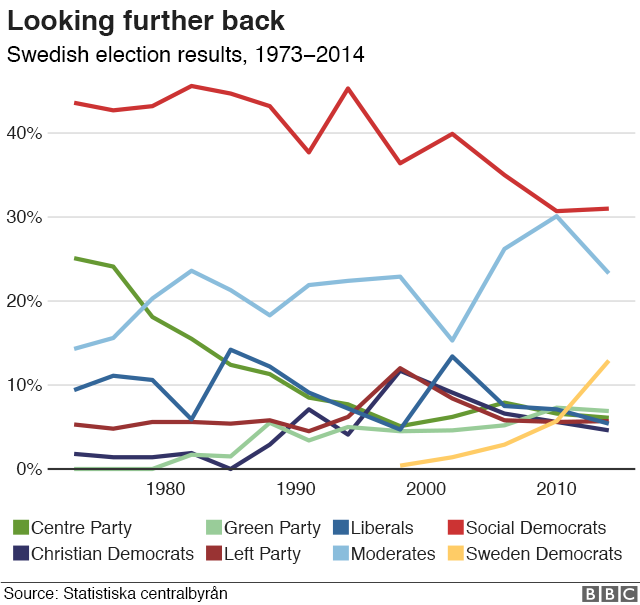

Their logo is a blue-and-yellow flower - the colours of the Swedish flag - and politically the nationalist Sweden Democrats (SD) are in full bloom.

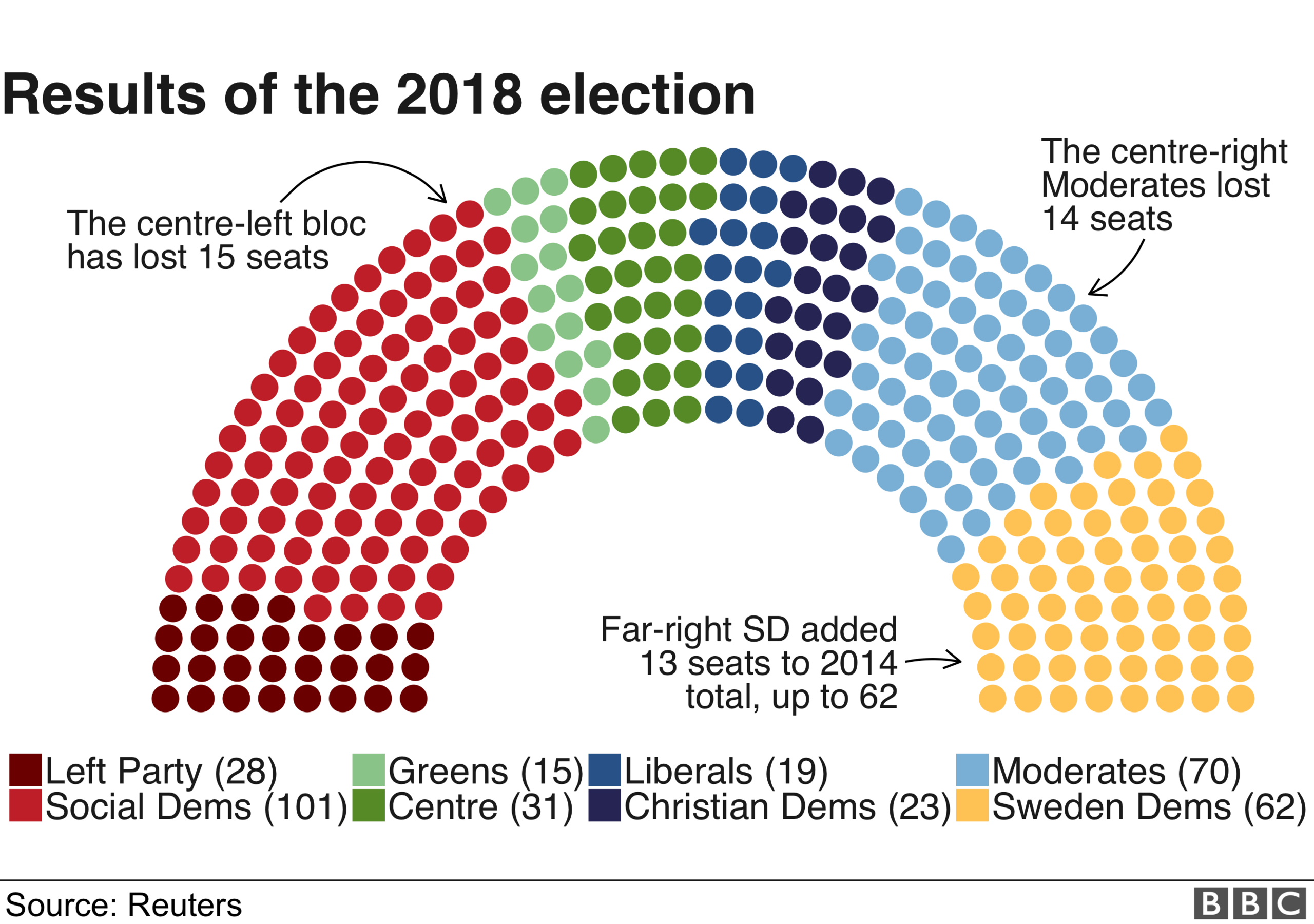

After entering the parliament with 5.7% of the vote in 2010 they went from strength to strength.

In the 9 September 2018 election they took 62 seats in the 349-seat parliament, increasing their vote to 18% from 13% four years earlier.

The SD has capitalised on widespread insecurity in Sweden about immigration.

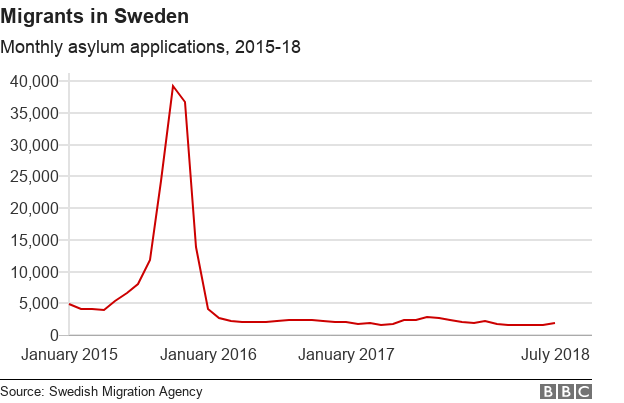

During Europe's 2015 migrant crisis Sweden took in a record 163,000 asylum seekers, many of them Muslims from war-torn Syria and Iraq. It was the highest such intake in the EU, per head of population.

Ten years ago migration was a minor issue in Swedish politics; now it is one of the top issues.

What does the SD say about migration?

The party opposes multiculturalism, the liberal mixing of cultures that Sweden's mainstream parties have espoused for years. Sweden has long been seen as a beacon of tolerance because of that liberal consensus.

The SD accuses the traditional centrist parties of "wrecking" social welfare by encouraging the arrival of foreigners - especially Muslims - who they argue do not share Swedish values.

"Most of the immigrants haven't had a chance to become part of Swedish society and of course many of them have been Muslims and many segregate in suburbs around the big cities and build parallel societies," SD leader Jimmie Akesson told the BBC.

The SD manifesto says "we want to stop receiving asylum seekers in Sweden and instead go for real aid for refugees". "We want to enable more immigrants to return to their native countries."

Shootings have risen in Sweden - something the SD links to the rise in immigration, although official figures show no correlation. Much attention has focused on Malmo's troubled, mainly immigrant Rosengard district.

Gun crime in Malmo has been a hot topic

What are the SD's origins?

It was founded in 1988, with the goal of defending Swedish values and cutting immigration.

It has neo-Nazi roots - the founder members belonged to white supremacist groups.

But to win votes in liberal Sweden the party had to shed those racist connections and become more mainstream.

Enter Jimmie Akesson, who became leader in 2005 and pursued zero tolerance towards racism in the party. Several members were expelled.

He led an SD youth branch when he was still at school. Now 39, he hails from Soelvesborg, a small southern town, and studied political science before entering local politics.

"There are still some neo-Nazis in the party," said Anders Sannerstedt, a political scientist at Lund University in southern Sweden.

"Akesson said people who in their teens had Nazi links should be forgiven and should be open about it. They still have a lot to do, but they've been more careful this time vetting candidates for election, nationally and locally," he told the BBC.

Who do they appeal to?

Mr Sannerstedt says Mr Akesson's drive to broaden the SD's appeal has worked and, like some other rising nationalist parties in Europe, it has a populist agenda setting it apart from the political "establishment".

The SD is very active on the internet, knowing that many of its supporters "don't trust traditional media that much, so they are looking at social media instead", Mr Sannerstedt says.

Politically it is closer to the nationalist Danish People's Party than to the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), he says. In the European Parliament the SD is in the same Eurosceptic group as the UK Independence Party (UKIP).

The SD is strong on issues that especially vex poorer sections of society: not just immigration, but also healthcare, law and order and pensions. Across Europe many voters accuse established parties of neglecting those issues.

The anti-euro SD also wants a "Swexit" referendum - to give Swedes the choice of leaving the EU. But the powerful centrist parties all oppose such a vote.

Can Mr Akesson get them into government?

"The SD won't join a government, it's out of the question," according to Mr Sannerstedt. "The other parties don't want to co-operate with them."

Coalitions with the SD may be possible, however, on some local councils.

The SD's rise has put the immigration issue centre-stage in Sweden and even in opposition it can heavily influence policy.

Patiently Mr Akesson has strengthened the party organisation, making it a big force to be reckoned with.