Ukraine crisis spells Arctic freeze in Russia-Norway ties

- Published

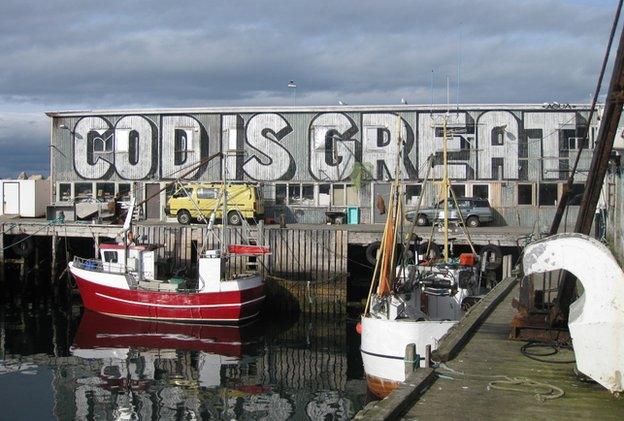

Vardoe's hardy people have a 500-year tradition of cross-border trade, based largely on fishing

Norway has responded to Russia's actions in eastern Ukraine by adopting the same array of sanctions as the European Union. But many Norwegians living on the north-eastern border with Russia are less than happy.

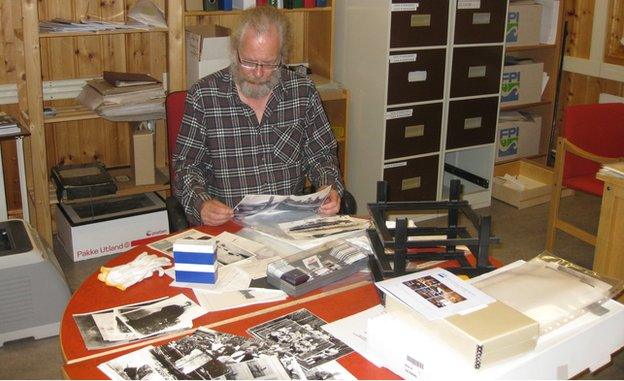

"We have worked hard for the last 20 to 25 years to establish people to people connections with Russia and now Oslo is destroying this," says Knut Stenhaug, a researcher at Vardoe museum.

An Arctic town, Vardoe sits on a small island in the Barents Sea, just off the coast of the Varanger peninsula. Its hardy population endures a nine-month winter and tough conditions for the rest of the year.

Once a thriving fishing community, the town's past glory was built on the cross-border trade with Russia, which dates back 500 years.

A lot has changed since Knut Stenhaug's great grandfather came here during its boom years of the 19th Century.

In the 1980s, local industry fell victim to large companies, and most fisheries closed.

Few benefited from the decline beside street artists. But what remained was a camaraderie with neighbouring Russians, along with a shared culture and, many believe, far more.

"Northern Russians are polite and quiet, not pushy, just like us," says Mr Stenhaug, referring to the inhabitants of north-west of Russia, along the coast in Murmansk, farther east in Archangel and beyond.

Vardoe museum researcher Knut Stenhaug pores over Russian trade archives

Vardoe's closed fisheries are decorated with eye-catching street art

"We think of ourselves as sharing a common genetic connection to the Barents region," says local artist Asbjorn Nilsen, who wonders whether the regions could maintain relations and steer clear of politics.

"Political ambition is the biggest problem. Here in the northern regions we don't have these political barriers."

In 1993, not long after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Norway set up the cross-border Barents Secretariat to bring the neighbours together.

In the centre of Kirkenes, 15km away from the Russian border, the secretariat's head, Rune Rafaelsen, says: "Every project here is focused on Russia.

"There is not a single institution in northern Norway that hasn't got a Russian partner. University, colleges, hospitals, local businesses - everybody has a Russian connection".

Russian influence in Kirkenes is hard to miss

Russia's influence in Kirkenes is hard to miss.

With 400,000 Russians coming across the border annually, it is no surprise that road signs, street names, businesses and even the local library have signs in Russian.

There are rusty Russian ships in the harbour maintenance dock, shops are filled with tourists from the Murmansk region and bars are buzzing with drunken youngsters with Slavic accents.

Mr Rafaelsen's organisation focuses mainly on small cultural and research projects. But although the number of applications recently has increased, he is anxious about the future.

"We will probably see a new climate in Russia, I am a little pessimistic for the next 30 to 40 years," he says.

Since the beginning of the crisis in eastern Ukraine, Norway has found itself caught between its Russian neighbour on one hand and the EU on the other.

A member of Nato but not the EU, the government in Oslo followed Brussels' lead in imposing sanctions, and Russia retaliated by banning imports of Norwegian fish.

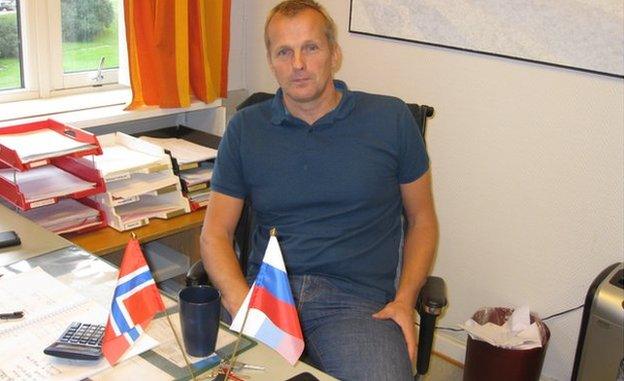

Brede Saether's Russian employees have been left stranded by their own government's sanctions

That import ban has hit Brede Saether hard.

His 20-year-old cross-border company, Kirkenes Trading, has a £12m (15m euros; $20m) annual turnover but is now on the brink of closure.

Although he has another active business in Kirkenes, his 20 Russian employees over the border in Murmansk are now left in limbo.

"I am exhausted and it is not only about the sanctions. The Russians could just change their laws at any moment. I am thinking of getting out of the country entirely," he says, in an office full of Soviet-era memorabilia.

Until now, Russia has been Norway's biggest seafood export market.

But with the ban in August, export values plummeted by almost £43m - 80% down on the previous year.

Fishing companies with the greatest exposure to Russia are already suffering from the sanctions

Industry insiders are optimistic that the majority of companies will be able to bounce back quickly.

For Svein Ruud, chief executive of Norway's King Crab AS and Troika Seafood, it could just be a matter of months to make up the 15-20% of lost annual exports.

"Chilean salmon will now go to Russia and we will have a bigger share of the US market, where Chilean salmon used to go," he says. "We will be fine in the end, but it is disappointing to ruin relationships which took 20 to 30 years to build".

But for Brede Saether, whose entire business is focused on Russia, things are very different.

"I thought Russia was moving in the right direction. But I am disappointed in Russians: they see everything through (President Vladimir) Putin's eyes. I definitely see an increase in nationalism in the last one-and-a half years."

Going through his shelves full of Russian books, souvenirs and photos, Brede has fond memories of his time across the border but now believes too much has changed.

"It is really sad, but I will not return to Russia even if they turn back the sanctions. I've had enough."

- Published28 August 2014

- Published22 August 2014

- Published3 September 2014

- Published13 November 2014