Germany struggles to adapt to immigrant influx

- Published

The Turkish are now an established community in Germany

"Everyone's moving to Germany."

So says Govan, a thin, bearded French jazz musician from Lyon whom I meet in a German language class for people recently arrived in Berlin.

"In one month," he says, "I met lot of people from everywhere."

The faces around the table are young, the accents mainly European. They tell a story about how the demography of this country is changing fast.

Germany is now the world's second most popular destination - after the US - for immigrants. And they are arriving in the hundreds of thousands.

Net migration to Germany has not been this high for 20 years, and even the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) describes it as a boom, external. In 2012, 400,000 so-called "permanent migrants" arrived here.

They are people who have the right to stay for more than a year. That represents an increase of 38% on the year before.

They are coming from Eastern Europe, but also from the countries of the southern Eurozone, lured by Germany's stronger economy and jobs market.

And they are being welcomed with open arms - by the government at least - because Germany has a significant skills gap, and a worryingly low birth rate.

"Immigrants are on average younger and the German population is on average older, so immigrants are welcome," says Dr Ingrid Tucci, from the German Institute for Economic Research.

"It's important to attract students and highly qualified people. So the government is making it easier for them, trying to invest and put a culture of welcome in place."

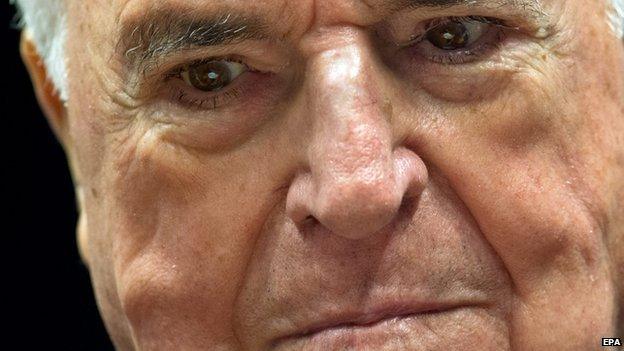

Former Chancellor Helmut Kohl didn't want Turkish immigrants to settle permanently

Here they call it "Willkommenskultur, external".

In practice it means free or cheap German language lessons for immigrants plus integration and citizenship classes.

As Berlin's senator for work, integration and women, it is Dilek Kolat's job to facilitate Willkommenskultur in the city.

"Every academic, every employer will tell you we need skilled migration. There's a change in perception in wider society.

"We don't look at migrants as a possible threat or a possible problem, but we look at them as potential.

"What can they bring to society? Business[es] are approaching the senate and asking how can we get the young refugees into apprenticeships which at the moment aren't taken up by German kids."

But Willkommenskultur is also about attitude.

And - politically at least - it's changed substantially since the days of Helmut Kohl.

Under his leadership Germany was 'not a country of immigration' despite the hundreds of thousands of Turkish migrant workers who'd been invited here in the sixties.

They had been recruited to help with Germany's post-war reconstruction.

And - as their families and friends arrived to join them - Germany's immigration figures spiked for the first time since the Second World War. In 1970 for example annual net immigration stood at more than half a million.

Private papers recently published by the German news website Spiegel Online reveal Chancellor Kohl told then UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1982 that he wanted to halve the number of Turks living in Germany. They did not, he said, "integrate well".

Today they are an established community. Stroll through the Berlin district of Neukoln and you pass hundreds of businesses run by their children and grandchildren.

In the window of one of the restaurants here, a large chunk of roasting meat turns slowly on a spit. Inside, a woman with a headscarf sips tea from a glass in front of a counter stacked with kebabs and and flatbreads ready for the lunchtime rush.

It is owned by Hassan - an earnest man in his 40s, who arrived in Germany with his parents when he was 13. But he worries about immigration today.

'It's great people come to Germany. They should be able to come. But people who don't work shouldn't be able to stay. Look at me - I work 20 hours a day.

"There are a lot of beggars. They have no money but ask for food. I give them kebabs, pizzas, but my heart breaks - I can't give food to everyone."

Neither, it seems, can some German towns and cities, who are largely responsible for the welfare of immigrants.

Leaders of the anti-euro AfD want tighter controls on immigration

Last year the mayors of 16 large German cities wrote to the government asking for help with unemployed migrants flooding into their regions from Eastern Europe. Places like Cologne, Dortmund and Hanover have struggled to cope.

And there is growing support in Germany for a new political party. Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) acknowledges the need for migrant workers but still wants tighter controls on immigration.

This, though, is a country still haunted by the atrocities of World War Two.

People here are mindful of how devastating the consequences of "Rassenhass" - racial hatred - can be.

And bear in mind most of today's migrants are moving within the EU.

Since Bulgaria and Romania acceded in 2007 there's been a significant increase of immigrants from both countries - 67,000 Romanians and 29,000 Bulgarians arrived in the first half of 2013.

In response to public concern about the numbers, Angela Merkel's government pledged to crack down on migrants who fraudulently claimed benefits but - in the words of one politician from her conservative CDU party - free movement for workers is "one of the main pillars of the European Union".

So, as Dr Tucci says: "There aren't a lot of tensions - Germany doesn't compare with countries like France where tensions are more virulent.

"It's important though to say the population has to be prepared for immigration. There are perhaps fears of newcomers. So political rhetoric is important."

Back in the language class, I meet Alissa and David - an architect and a musicians' agent - who have arrived from Milan.

"We discovered that Milan was too expensive for us and the quality of life was not so good," says David.

"We had some money and we decided to buy a flat here in Berlin because it was cheaper than Italy.

"We were looking for a real metropolis, and in Europe the big cities are too expensive. Berlin was the only solution. The only problem is the language."

But, adds Alissa: "I feel at home."

She is in good company. More than 7.6 million foreigners are registered as living in Germany. It is the highest number since records began in 1967.

In the words of President Joachim Gauck: "A look at our country shows how bizarre it is that some people cling to the idea that there could be such a thing as a homogenous, closed single-coloured Germany.

"It's not easy to grasp what it is to be German - and it keeps changing."

- Published2 September 2014

- Published7 May 2014