Ebola: WHO under fire over response to epidemic

- Published

The Ebola outbreak has killed nearly 5,000 people, the majority of them in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone

The World Health Organization (WHO), set up by the United Nations in 1948, is the world's biggest and most important public health body.

There is no question that it has had some major successes: it has ensured that millions of children worldwide are free from the danger of polio, the crippling virus is now endemic in just three countries.

It runs huge programmes aimed at combating HIV/Aids, malaria and tuberculosis, and its Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is ensuring that countries are banning smoking in public places and clamping down on tobacco advertising.

But when it comes to a sudden new health threat, or a danger in an unexpected region, many say the WHO does not really deliver.

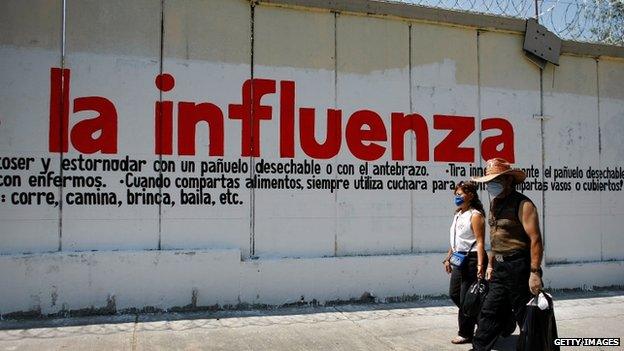

The 2009 swine flu pandemic is, it is claimed, a case in point.

Unstoppable

When the first cases of a new flu virus were reported in Mexico City, the WHO had already been preparing for a global influenza pandemic with many experts suggesting it could be as devastating as the post-World War One Spanish flu.

There were reasons for the fears. Medical historians knew that a serious flu pandemic could be expected once in a generation.

Furthermore the H1N1 "bird flu" virus did have a high mortality rate, although it had not shown much ability to spread from human to human.

The swine flu outbreak in Mexico in 2009 caused widespread alarm

So by 2009 the WHO had a huge "pandemic preparedness" plan, and when swine flu appeared, it swung into action.

A global pandemic was declared and pharmaceutical companies fast-tracked billions of doses of a new vaccine.

Many countries diverted their public health budgets in order to buy a dose for every single member of the population.

The problem was, swine flu was not the major global health threat the WHO had been preparing for.

"What we experienced in Mexico City was a very mild flu which did not kill more than usual," said German epidemiologist Wolfgang Wodarg in 2010.

"(It) even killed less people than usual, it was suddenly used... as a pandemic and I asked myself why does WHO do such a nonsense?"

But the voices raising doubts went largely unheard. The WHO's pandemic preparedness had been long in the planning and, once up and running, seemed unstoppable.

Unexpected

And the very planning that went into preparing for an influenza pandemic seems have to worked against the WHO during West Africa's Ebola outbreak.

Although a flu pandemic was expected, Ebola was most definitely not expected in Liberia, Guinea or Sierra Leone. The virus had never been seen in West Africa before.

So when the first cases were reported in March there was no big WHO machine ready to roll. As it turns out, West Africa's Ebola outbreak actually began in Guinea last December and seems to have gone almost unnoticed for three months.

"Nobody knew that this disease called Ebola would be possible in such parts of Africa," said Dr Isabelle Nuttall, the WHO's Director of Global Capacities, Alert and Response.

Dr Isabelle Nuttall has defended the WHO's response to the Ebola outbreak

"The speed of reaction was initially determined by the fact that the disease was not known to occur in this part of Africa."

Failure to listen?

But even if the WHO did not expect Ebola in West Africa, it did receive information, and warnings, from medical experts on the ground.

Medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) said on 31 March that Guinea was facing "an epidemic of a magnitude never before seen in terms of the distribution of cases in the country".

The organisation warned that the geographic spread of the cases indicated the epidemic would be very difficult to contain.

But just one day later, on 1 April, the WHO's senior communications officer, Gregory Hartl, suggested that MSF was scaremongering.

"We need to be very careful about how we characterise something which is up until now an outbreak with sporadic cases," he said.

"What we are dealing with is an outbreak of limited geographic area and only a few chains of transmission."

For the following three months, the WHO continued with that interpretation. Meanwhile media attempting to report the obviously spreading epidemic faced major hurdles.

Ebola is of huge concern across West Africa, including here in Ivory Coast

The WHO's regional headquarters in Africa issued irregular online statements as to new cases and death tolls, which were often not confirmed by WHO headquarters in Geneva for several days.

Calls to communications officers went unanswered, their voicemail boxes were full.

Only in June did the WHO call a meeting of its Global Outbreak Alert committee, and only then, it seems, did WHO Director General Margaret Chan take a long hard look at the situation, telling Bloomberg's news agency last week that she was "very unhappy" at what she had discovered.

Despite her dissatisfaction, it still took the WHO until August to declare Ebola to be a health emergency.

Budget cuts

Today, although Nigeria has just been declared Ebola free, the epidemic is still raging in Guinea, where it began, and in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The WHO admits there is no sign it is even close to being brought under control and almost 10 months after it first began this outbreak has claimed at least 4,500 lives - more than three times the death toll from all previous outbreaks put together.

An embarrassing internal WHO document, leaked to the Associated Press last week, indicates senior WHO officials know mistakes have been made, suggesting "nearly everyone involved in the outbreak response failed to see some fairly plain writing on the wall".

The WHO has refused to comment on the document, but some suggest the financial cutbacks that the WHO, like all United Nations agencies, is facing, may be part of the problem.

However, others argue that money shortages should not cause a failure to listen to clear warnings and should not have caused months of delay in recognising the extent of the Ebola epidemic.

The WHO says it will investigate its handling of the crisis but not until the outbreak is over.

What is clear is that the organisation's structure, designed decades ago to support carefully planned, long-term public health campaigns, will need a major re-examination and there will be calls for more flexibility and transparency when facing the next sudden health crisis.