Polish museum celebrates 1,000 years of Jewish life

- Published

The ceiling of a 17th Century wooden synagogue from Gwozdziec was painstakingly reconstructed

A new museum in Warsaw tells the rich and complex story of 1,000 years of Jewish life in Poland.

Jews first settled in Poland in the early Middle Ages. From about the 17th Century until the beginning of the 20th Century, the country was the global centre of Jewish life.

In 1917, Jews accounted for 44% of Warsaw's population. The Jewish district was a noisy, bustling collection of streets covered in shop signs advertising small workshops that produced everything from ties to artificial flowers.

That vibrant community with its synagogues, theatres and political representation was wiped out during the Holocaust.

Warsaw ghetto

Now, for the more than one million Jewish and other foreign visitors, who every year travel to the remains of the death camps that the Nazis built in occupied Poland, the story of the Holocaust overshadows the centuries of life that went before it.

"The last thing Poland needed was a Holocaust museum because the whole country is a Holocaust museum," says Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, programme director of the museum's core exhibition.

"We have a moral obligation to remember not only how Jews died but also how they lived, lest the world knows more about how they died than how they lived."

The Museum of the History of Polish Jews stands on the site of the former Jewish ghetto, beside the monument to young men and women who died resisting the Nazis' attempt to destroy the area in April 1943.

The museum stands on the site of the former Jewish ghetto

Promised land

Its walls are made of glass and have the Hebrew word for Poland silk-screened on to them. Above the main entrance a crack opens to the ceiling, creating a canyon through the middle of the building, like Moses parting the waves of the Red Sea.

Moses was on the mind of Marian Turski, an Auschwitz survivor who sits on the museum's council, when I asked him for his thoughts on the completed building.

"Moses' contributions to the Jewish nation cannot be calculated because they are so great, and he was not allowed by God to enter the Promised Land. So imagine myself, who merits nothing, and I got it. I was allowed to enter this promised land, to fulfil my dreams," he said.

The exhibition uses city models, maps and video to tell 1,000 years of Jewish history

The exhibition will be officially opened by the presidents of Poland and Israel on Tuesday

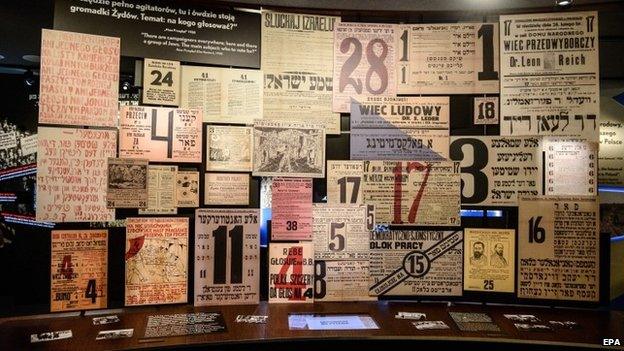

Among the exhibits are election campaign posters in Yiddish and Polish

Through a combination of medieval city models, maps, film, photographs, audio, and touch-screens, the exhibition, which will be officially opened by the Polish and Israeli presidents on Tuesday, tells the story of the first Jewish settlers from 960 to the present day.

Thorny issue

It shows how Jews fled expulsions and wars in Western Europe to come to Poland, bringing a monetary and credit economy with them. Polish rulers gave them the right to settle, form communities, follow their religion and engage in certain occupations.

One of the jewels of the exhibition is a reconstruction of the ceiling of a 17th Century wooden synagogue from Gwozdziec, with its gorgeously painted images of animals and signs from the zodiac.

The exhibition has sparked a discussion about its priorities. Some members of Warsaw's Jewish community say the synagogue is "amazing" while not really giving much information about Judaism.

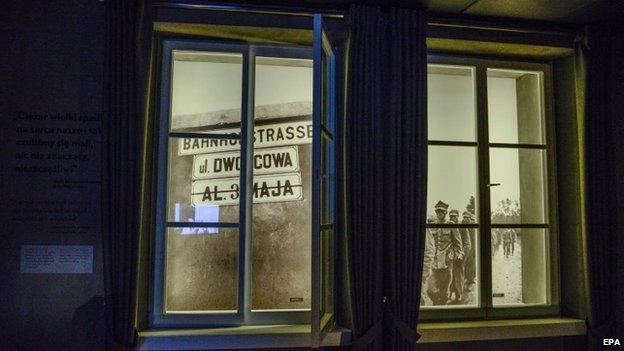

One gallery depicting an Industrial Revolution-era railway station is twice as large as the exhibit on Hasidism, which was founded in the first half of the 18th Century in Poland and had a major impact on the Jewish world.

The thorny issue of Polish-Jewish relations under the Nazi occupation is presented in a balanced way, ranging from Poles who supported the Nazi extermination of the Jews to those Poles who risked their lives trying to help them.

The exhibition also highlights the Poles who risked their lives to help Jews under Nazi occupation

A passageway of rusted metal with a faint burnt smell depicts the death camps. The post-war galleries show how many of the returning survivors chose to emigrate rather than face suspicion, pogroms and communist-led anti-Semitic campaigns.

The exhibition ends with today's small Jewish community.

"Here in Poland I think this museum can make an enormous difference in the renewal of Jewish life. The renewal is small, the community is small, but that doesn't make it any less important," says Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett.

"Why the Jewish community is so small, is not only as a result of genocide, emigration, assimilation, and communism, but because of the fear and the shame that led parents to conceal or keep secret the Jewish roots of their children and grandchildren," she says.

Jewish roots

One such example is Anna Chipczynska, the head of Warsaw's Jewish community. She was only told by her parents she was Jewish as an inquisitive teenager who loved reading Isaac Bashevis Singer's stories of Jewish Poland.

"You usually hear like I heard, 'Well, you know what, I have to tell you something: we have a Jewish background'," she said. "But it wasn't said as something good, because for my parents' generation it was a threat to be Jewish," she added.

Poland's communist rulers made all things Jewish a taboo subject. Since communism fell in 1989, there has been a revival of interest in Jewish history amongst both non-Jewish Poles and those who have recently discovered their Jewish roots.

Ms Chipczynska says there are 5,000-7,000 registered Jews in Poland now, and perhaps 25,000 people with Jewish roots.

"Being Jewish in Poland is a thing that you are developing. You are basically building your own identity; you have to answer your own questions about what it means to be Jewish," she says.

The exhibition ends with today's small Jewish community in Poland

Poland's Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich believes the new museum may help shape this identity.

"It's going to be a place where Poles discovering their Jewish roots will feel proud to be Jewish and take their first steps to the discovery of what Judaism is about," he says.

As president of the board of the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland, businessman Piotr Wislicki helped secure funding for the project following the global financial crisis.

He recalled seeing three generations of a Jewish-American family leaving the museum two weeks ago.

"I saw the children and grandchildren smiling and the grandparents crying. I said, 'What happened? Was it the Holocaust gallery?' They said, 'No, we're happy that at the end of our lives we were able to show our children and grandchildren our splendid story, how life really looked like in Poland'," he said.

- Published19 April 2013

- Published19 April 2013

- Published20 April 2012