Russian Soviet-era remembrance group Memorial risks closure

- Published

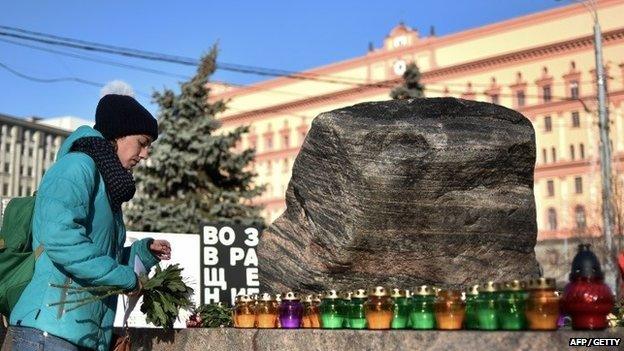

The "Bringing Back Names" ceremony outside the old KGB headquarters lasts for 12 hours

Every year at the end of October a crowd gathers in central Moscow next to a large stone, brought from a Soviet prison camp.

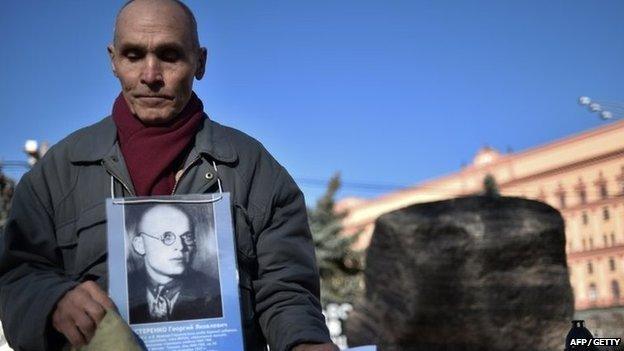

As music plays quietly, people step up to a microphone, one by one, and read out a list of names.

After each name comes a date and one, stark word: "Shot."

The ceremony is organised by Memorial, Russia's oldest civil rights group established in the late 1980s by dissidents including Andrei Sakharov.

It works to restore the memory of the hundreds of thousands of victims of Soviet political repression.

But Russia's justice ministry has called for Memorial to be "liquidated", throwing the group's future into doubt and raising protest at home and abroad.

The stone comes from the Solovky Islands, where one of the first Gulag prison camps was built in 1923

The naming ceremony comes on the eve of a day of remembrance for victims of Soviet-era repression

"The aim is to put pressure on independent, civil society," argues Memorial's Alexander Cherkasov, who says the ministry's complaints concern details of how Memorial and its numerous national branches are registered.

Memorial's leaders contacted the ministry to discuss the new requirements at a conference called for late November, but they won't have a chance. They have been summoned to a Supreme Court hearing on 13 November which will rule on the organisation's closure.

"They want to shut us down," Mr Cherkasov believes. "There's no understanding that groups like this are an important part of a healthy society."

This summer, Memorial's human rights wing was forcibly registered as a "foreign agent" under a new law singling out groups that receive grants from overseas.

Over the years, its activists have been a regular thorn in the government's side, documenting human rights violations in Chechnya, political detentions, and more recently criticising Russian involvement in the crisis in Ukraine.

A sign on the square recalls that in 1937-38 more than 30,000 people were executed in Moscow alone

But highlighting the darkest episodes of Russia's past may also be unpopular, when politicians are busy stoking national pride and recalling more glorious eras.

"It may be a political gesture, to shrink the possibilities for organisations like Memorial," said EU Ambassador to Russia Vygaudas Usackas.

He called for Russia to demonstrate that such concerns over free speech were ill-founded, by giving the group time to comply with new regulations.

Russia's foreign ministry rejects all suggestion that the case is political: the justice ministry has uncovered "violations" at Memorial that need addressing, a statement reads.

Memorial's future will be decided at a Supreme Court in November

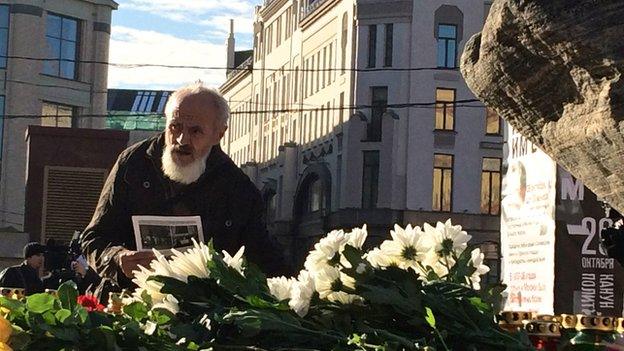

But those gathered around the Solovetsky stone were sceptical.

"I think it's an attempt to stop what we're doing now," Elena Bagrimenko says, after laying a candle and flowers beside the memorial stone.

Her own great grandfather was a priest, killed in the purges - Stalin's deadly, paranoia-fuelled drive against supposed "enemies of the state".

"Of course we are worried," she adds as others intone more names in the background. An economist, a hospital accountant, a peasant - all shot.

Stalin's Terror

"If Memorial is stopped our history will be silenced and the victims forgotten, just as we were beginning to remember them," she argues.

"If we don't remember these things, they can repeat and I'm afraid they will," adds Mikhail Markovich, who believes that political repressions in Russia are increasing again.

But he takes hope from the large crowd queuing to recall the victims of Stalin's Terror.

A sign on the square recalls that in 1937-38 more than 30,000 people were executed in Moscow alone. Without the work of Memorial, their names and their stories may never have been known.

- Published22 March 2013

- Published21 July 2012

- Published22 May 2012

- Published17 March 2024

- Published25 March 2024