Czech Republic Slovakia: Velvet Revolution at 25

- Published

Is the spirit of the Czech Republic's Velvet Revolution still alive in Prague?

Czechs and Slovaks are looking back at the heady events of 1989 when communism fell before their Velvet Revolution, the BBC's Simona Kralova writes.

A quarter of a century ago, on a fairly typical November day, thousands of university students gathered in the Czechoslovak capital, Prague, for a peaceful demonstration to commemorate International Students' Day.

Little did they know that their seemingly innocuous protest would trigger the momentous events which would in effect end the rule of communism in the country a mere 10 days later.

That peaceful student protest on 17 November, which ended with brutal violence in central Prague when riot police blocked off escape routes and severely beat students taking part in the demonstration, led to what would later become known as the Velvet Revolution, an avalanche of popular protests, held almost daily in Czech and Slovak cities.

Students surround a tram covered with posters of Vaclav Havel for presidency during a protest rally in Prague on 17 November 1989

Protests gather pace as students mark International Students' Day

Riot police bar the bridge leading to Prague Castle, the seat of the Czechoslovak presidency, on 19 November 1989

It culminated in the appointment of the country's first non-communist government in more than four decades and the election of Vaclav Havel, a playwright turned dissident, to the post of president.

Alexander Dubcek, the reform communist hero of Prague Spring, was elected the federal Czechoslovak Speaker. The communist government, discredited and powerless against the demands of protesters, had to admit defeat and step down.

Everyone lived

This non-violent transition of power earned its moniker primarily for its peaceful nature - not a single life was lost during the process.

It is fair to say that the Velvet Revolution would not have been possible were it not for the dramatic developments unfolding in the other communist bloc countries. In particular, the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November in neighbouring East Germany gave many Czechoslovaks hope of possible change in their own country.

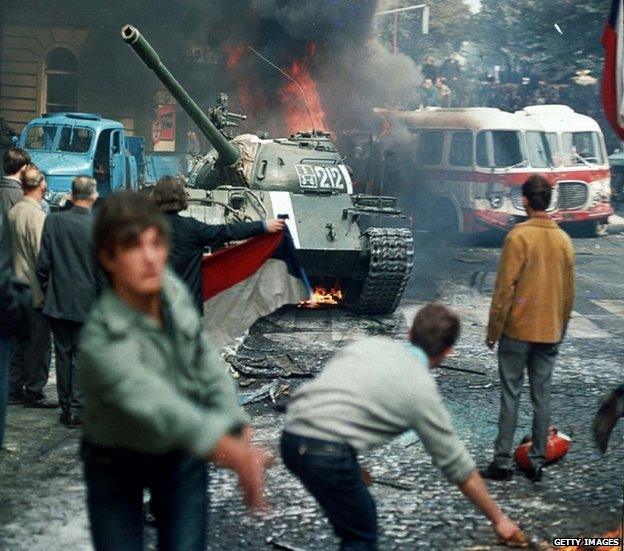

But despite the wave of reform that was already sweeping through Europe, many feared a repeat of the dramatic events of 1968 when, on the night of 20-21 August, Warsaw Pact troops led by the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia to halt political liberalisation, also known as the "Prague Spring".

Many had feared a repeat of the 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia

It is not possible to mention the Velvet Revolution without mentioning the Velvet Divorce - the amicable dissolution of Czechoslovakia, which took effect on 1 January 1993 and saw the self-determined split of the federal state into the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Although many citizens of the two countries are still convinced that this was not a wise step to take, it was arguably one of the most notable political achievements in post-communist Europe. The break-up was accomplished peacefully, following the example of the bloodless transfer of power three years previously.

There is no doubt that the consequences of those dramatic events of 1989 put Czechoslovakia on the path to democracy. Restrictions on the media, speech and travel were lifted. The new, democratic government liberalised the country's law with respect to both politics and the economy, creating an open and free society.

Nostalgia

But as both countries prepare to mark a quarter of a century of freedom, a survey conducted recently by the Public Opinion Research Centre suggests a full sixth of Czechs still long for a return to communism.

They appear equally split on whether their country's current political leadership is moving the country forward.

Other research, carried out by the Medea agency, suggests that although 84% of Czechs are aware that 17 November is celebrated as a national holiday to remember the Velvet Revolution, only 30% of people below the age of 30 are aware of this. The poll also suggests that only three out of five people think their quality of life is better now than it was before 1989.

Similarly, in Slovakia there is disillusionment with the current government and its policies. The leading party, Smer, was forced to cancel a concert planned to coincide with the anniversary after performers expected to take part pulled out because they did not want to be associated with the party.

Despite that, most citizens of the former federation remember the euphoria of 1989 with nostalgia and fondness, and the younger generation mostly appears to be fully aware of the significance of the revolution.

There were jubilant celebrations after Vaclav Havel was elected president in December 1989

Fedor Gal, a Slovak politician and sociologist who has lived in Prague since 1991 and was one of the leading protagonists of the 1989 revolution, summed up similar sentiments in a recent interview: "We keep complaining and whinging, despite the fact that our life is good!"

And Czech ex-President Vaclav Klaus echoed this view in an interview with the Czech weekly Echo24: "Without looking at the past 25 years through rose-tinted glasses, I think that our transformation was a success. The basic goal associated with the fall of communism was freedom. November 1989 gave us this freedom."

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.