Erdogan's 'New Turkey' drifts towards isolation

- Published

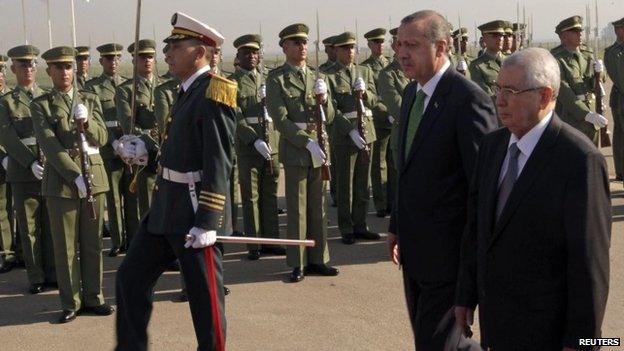

President Erdogan (centre) has found himself to be increasingly isolated on the world stage

There is an old saying in Turkish: "The Turk has no friend but the Turk." As this country drifts towards isolation under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the proverb is ringing uncomfortably true.

During his 11 years as prime minister, Turkey rose in prominence. It began negotiations for European Union membership. It hugely increased its diplomatic presence, particularly in Africa. Its biggest city, Istanbul, now hosts one of the world's largest airport hubs with an airline that flies to more countries than any other.

But in the past months, perhaps two years or so, something has soured. The world's statesmen still stop by - the US Vice President, Joe Biden, arriving this week - but Turkey today is distinctly lacking friends.

When the UN General Assembly voted last month for new non-permanent members of the Security Council, Turkey confidently assumed it would secure a seat. But, humiliatingly, it lost out to Spain and New Zealand: A slap in the face for Mr Erdogan, elected president in August.

Turkey has been transformed under Mr Erdogan's leadership from a financial basket-case to the world's 17th largest economy

Mr Erdogan has made clear that he has little time for people who have taken to the streets to protest against him

It began with the "Arab Spring". Turkey placed the wrong bets, backing the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and banking on a swift overthrow of President Assad. Now it has no ambassador in Cairo, Mr Erdogan denouncing his Egyptian counterpart Abdul Fattah al-Sisi as an "unelected tyrant".

And Turkey has been inexorably drawn into the nightmare in Syria, lambasted for allowing foreign jihadists to cross its borders. Ties with Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia have weakened.

And a former strategic partnership with Israel lies in tatters - the ambassador to Tel Aviv has been withdrawn, Mr Erdogan comparing the country's bombardment of Gaza to "genocide…reminiscent of the Holocaust".

But now even relations with old allies like the US have sunk. As Washington built a coalition to fight Islamic State, Turkey stayed on the sidelines, refusing to let the US use its airbases here for strikes unless it also targets President Assad and backs a no-fly zone in Syria.

A few hours after Mr Erdogan warned President Obama last month not to arm Kurdish fighters in Syria, the US airdropped weapons. There could hardly have been a clearer sign of discord.

'Unparalleled success'

"There is the realisation in government of what ground has been lost," says Sinan Ulgen of the Edam think tank, "but Ankara justifies it by alleging Turkey's isolation is because it's the only country courageous enough to adopt the moral high-ground and a value-based foreign policy.

Mr Erdogan has described Egyptian leader Abdul Fattah al-Sisi as an "unelected tyrant"

The president has been equally critical of the Israeli bombardment of Gaza earlier this year

"That argument is bought by Erdogan's constituents - and for him, that's what matters."

That is, ultimately, what drives Recep Tayyip Erdogan. His unparalleled success at the ballot box has given him the unshakeable conviction that his policies are the right ones.

The mass street protests in June 2013 sparked by a construction plan in Istanbul's Gezi Park didn't alter his path - while senior figures around him called for dialogue, he labelled the demonstrators "riff raff".

And he even bounced back from a devastating leak of private phone calls a year ago that implicated him and close allies in corruption allegations.

'Weakened influence'

He responded by denouncing an "attempted coup", firing thousands of judges and police and attempting to ban social media. He closed ranks, relying on arch-loyalists.

Turkey has refused to let the US use its airbases here for strikes against Islamic State militants in Syria unless it also targets President Assad and backs a no-fly zone

"The Gezi protests, followed by his reaction to the corruption claims, were when international opinion towards Erdogan turned," says Sinan Ulgen.

"Turkey's isolation is a problem for itself but also for the West. If the West wants to achieve its security aims in the region, potentially it has no better partner than Turkey.

"But with Turkey's influence weakened, the West is handicapped. Erdogan believes democratic legitimacy is about the ballot box. Others expect more from Turkish democracy - a free press, an independent judiciary and the rule of law."

In recent weeks, criticism at home has mounted - from the construction of a 1,000-room presidential palace costing over $615m (£392m) in protected forest - defying over 30 legal challenges - to verbal attacks on foreign journalists, to controversial statements about Muslims, rather than Columbus, founding America.

They have added to the sense of a government adrift.

'Economic powerhouse'

And yet, among his faithful, he retains his support. The 52% who elected him president care little about a Twitter ban or claims of corruption, which they believe swirl around most politicians.

For them, the transformation of a financial basket-case to the world's 17th largest economy in the past decade is what matters - new hospitals, roads and schools.

His supporters, mainly religious conservatives, feel liberated by their president's encouragement to wear headscarves in schools and universities, previously banned by 80 years of secularist rule. And they love his strongman image - the leader willing to stand up to the West.

Mr Erdogan has made Turkey "a political and economic powerhouse", according to his adviser, Ibrahim Kalin, which has "empowered the middle class".

He started "a new process to settle the Kurdish issue, has taken a number of historic steps to recognise the rights of religious minorities and has fought against military tutelage" - a reference to his widely-praised moves to blunt an army which overthrew four governments since 1960.

But the early successes of his leadership have been forgotten with his growing authoritarianism.

"In private, he's quite charming," a European official told me, "and can listen to advice. But in public, it's all about winning the fight. Compromise, checks and balances are signs of weakness. He'll naturally go in combative - and then realise a different approach may be needed."

The presidential palace has proved to be a controversial project for Mr Erdogan

The initial favour with the EU has faded with concerns about freedom of expression. As Turkey's progress towards membership has stalled and enlargement fatigue has set in, the EU's leverage here has weakened, heightening the sense of isolation.

"The good feeling towards him has dissipated - there is more cautiousness," admits the official. "But we want to keep the accession process going - and we want a more substantial relationship. There is an understanding of the importance of Turkey."

And that, internationally, is what gives Mr Erdogan the confidence he needs: That Turkey is still a crucial player. It is the West's stepping-stone to a volatile Middle East and is a rising economy that no side can ignore.

"Erdogan's own ambition is to become the greatest Turk ever," says the European official. "And even if our enthusiasm for him has been tempered, he's still the guy you have to do business with."

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is building what he calls a "New Turkey". Others call it a polarised, unhappy Turkey - and one where friends at home and abroad are fading fast.

- Published15 November 2014

- Published14 November 2014

- Published24 March

- Published28 October 2014

- Published20 October 2014

- Published12 September 2014