Russian cinema's 'masterpiece' Leviathan bucks backlash

- Published

Clip from Leviathan

Russia's much-acclaimed submission for Best Foreign Language Film at the 2015 Oscars is Leviathan - a bleak vision of provincial corruption in the land of President Vladimir Putin. It is also an example of an increasingly rare phenomenon in the Russian film industry today of artistic excellence trumping state ideology.

Director Andrey Zvyagintsev's new film tells the story of Kolya, a car mechanic battling to save his property from the machinations of the brutish and unscrupulous local mayor.

Played out against the harsh landscape of the far north, it is a vodka-soaked study of crooked dealing and moral decay sharply at variance with the image of Russia touted by President Putin and the Kremlin-controlled media.

Minefield

Andrey Zvyagintsev (seen waving with the cast at Cannes) still sees his future in Russia

The film was premiered in May at the Cannes festival, where it won the award for Best Screenplay. Since then, it has been gathering accolades and plaudits across the world. The Guardian's, external film critic Peter Bradshaw called it a "new Russian masterpiece".

Amid the acclaim, there has also been some incredulity that a film like Leviathan can still get made in Putin's Russia. The Observer , externaland BBC film critic, Mark Kermode, suspected it had "slipped under the authorities' totalitarian radar".

But Leviathan has had official backing all along the line. Over a third of its funding came from state coffers and in September it was nominated by the country's Oscars Committee to represent Russia at next February's Academy Awards.

Despite the official endorsements, Zvyagintsev make no secret of the difficulties of working in Russia's increasingly reactionary and restrictive political environment.

"It is like being in a minefield. This is the feeling you live with here. It's very hard to build any kind of prospects - in life, in your profession, in your career - if you are not plugged in to the values of the system," he told the Guardian, external's Moscow correspondent, Shaun Walker.

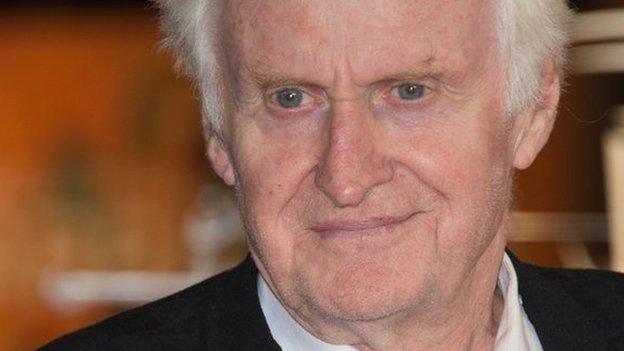

Vitaly Mansky, an award-winning film director, has complained about Russian media propaganda

One film-maker who is currently at odds with the system is Vitaly Mansky, who is also president of Artdocfest, Russia's largest international documentary film festival.

But this year, Artdocfest's funding was cut. In fact, Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky said that none of Mansky's projects would get any money as long as he was in post.

"With his anti-state rhetoric, he should finance the festival at his own expense," the ministry told journalists on 19 November.

The culture ministry had earlier turned down an application for Mansky's project Motherland - a look at the history of modern Ukraine told through the medium of the director's own family.

Mansky himself was born in Ukraine and in March he was one of the leading signatories to an open letter entitled "We are with you" - a message of solidarity from Kino Soyuz (Cinema Union) to Ukrainian film-makers who expressed dismay at the propaganda campaign against their country being waged in the Russian media.

Kino Soyuz was set up in 2010, and is a smaller rival to the official Union of Cinematographers of the Russian Federation presided over by Oscar winner Nikita Mikhalkov, a staunch supporter of President Putin and his policy on Ukraine.

Image

Some commentators have suggested that the culture minister's blacklisting of Mansky may be related to the "We are with you" letter. But Zvyagintsev was also among its signatories.

Film critic Anton Dolin thinks that, in the case of Leviathan, the desire for international prestige outweighed political or moral qualms.

"Though the film is extremely critical of the modern Russian state, this did not impede its promotion, because it works in favour of Russia's image as a leading country in the realm of cinema and culture," he told the Open Russia website.

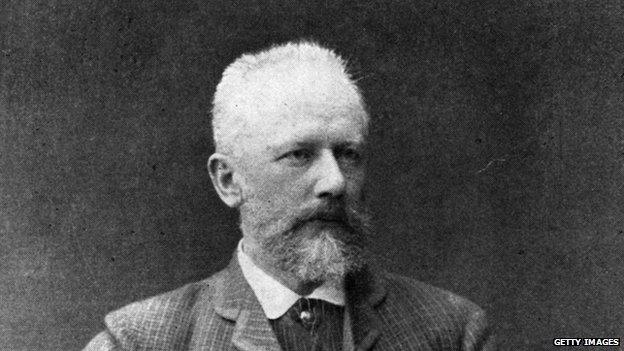

A film about the composer Tchaikovsky has been put on hold

But the list of cinematic projects facing problems in Russia is growing.

Director Kirill Serebrennikov's plans for a film about the composer Tchaikovsky has been put on hold indefinitely because of a lack of funding. It received a grant from the culture ministry but was turned down by another part of the state arts nexus, the Cinema Fund - apparently because of its portrayal of the composer's homosexuality.

Other films have been falling foul of a new body set up to enforce standards of historical "accuracy", and also the burgeoning array of extremism, incitement, blasphemy and obscenity laws coming out in Russia.

A drama about the deportation of the Chechen and Ingush peoples in 1944 - Ordered to Forget - was banned by the culture ministry earlier this year on the grounds that it might "inflame ethnic divisions".

More films could soon be sharing its fate.

Andrey Zvyagintsev says building a career in Russia is hard without "plugging into" the system's values

A draft government decree published online on 21 November lists as reasons for banning the distribution of films not only extremist content or language breaching new obscenity laws, but also material "denigrating the national culture or creating a threat to national unity and the national security of the Russian Federation".

Leviathan went on general release in the UK on 7 November. It is due in cinemas in Russia in February, though it will not be quite the same version as in the West. The earthy language will have to be edited out.

Despite these and other difficulties, Zvyagintsev still sees his future in his homeland rather than abroad.

"If there will be obstacles to what I do in Russia, for example the release of Leviathan or my next project; if everything turns what I want to do into Soviet-style gibberish, then, of course, I will be faced with that choice [to leave]. But that hasn't happened yet," he told US film critic Anne Thompson, external earlier this year.

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

- Published22 May 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published19 August 2014