Pope Francis tries to build bridges in sceptical Turkey

- Published

Pope Francis battled against indifference on his Turkey trip

"Long live the Pope, long live the Pope!"

The crowd was small, but passionate. The Catholic faithful here are few.

A mix of young and old, though, were waiting for the Pope to arrive at the Church of the Holy Spirit in Istanbul.

It is tucked behind a discreet doorway on a main road, and the pavement was sealed off behind a temporary security barrier.

Attendance at the special mass with Pope Francis was by invitation only.

When the Pope arrived at last, they gave him a rock star's welcome; youngsters desperately holding up their mobile phones to take selfies with the leader of the world's 1.2 billion Catholics.

The 77-year old Pontiff did not disappoint; he seemed energized by the cheers, smiling broadly as he was mobbed by his small Turkish flock.

Elsewhere in Turkey, though, there was little interest in his visit: no surprise in a nation of 77 million people that is now some 99% Muslim.

Its Christian minority was around 20% a century ago, but is down to well under 1%, or 80,000 people in total, while Turkey's Jews number just 17,000.

Key visit

This was nonetheless a key visit for the Pope, thanks to Turkey's importance as a majority Muslim nation that bridges two continents, looking both east and west.

It is also a NATO member deeply affected by the conflict on its borders, in Iraq and Syria.

Turkey now hosts over 1.6 million refugees fleeing the violence of the so-called Islamic State, the Sunni extremist group that has sought to rid the territory it takes of religious minorities, including Christians and Yazidis, as well as Shia Muslims.

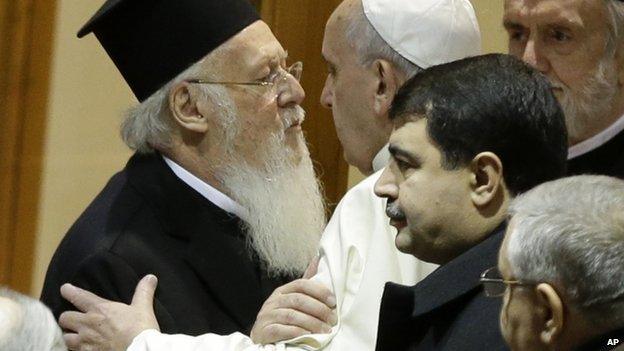

Relations between the two Christian church leaders were positive

In seeking to build bridges between Christianity and Islam, as well as with the Orthodox Church on his trip, this Pope proved more sure-footed than his predecessor, Pope Benedict, who walked into a diplomatic storm here over his attitude towards Islam during his visit to Turkey in 2006.

However, even though Pope Francis did not put a foot wrong diplomatically, this trip proved that building bridges with Islam, even in a secular state such as Turkey, is not easy.

As the Pope arrived at President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's sprawling new palace in Ankara, no mention was made of Mr Erdogan's speech just days before the visit.

The politician, from the Islamist-leaning Justice and Development (AK) party, had reportedly told an audience at an economic Islamic conference that: "Those who come from outside (the Islamic world) love oil, gold, diamonds and the cheap labour force of the Islamic world. They like the conflicts, fights and quarrels of the Middle East.

"Believe me, they don't like us. They look like friends, but they want us dead. They like seeing our children die."

West blamed

The Turkish president did make clear in person to the Pope on Friday that he blamed the West, external for the rise of Islamic State (IS).

President Erdogan said extremist groups such as IS were a consequence of the "serious and rapid rise of Islamophobia" in the West, warning that the sense of "rejection" among Europe's Muslims was one of the factors behind the radicalization of young men joining violent groups.

"Those who feel defeated, wronged, oppressed and abandoned ... can become open to being exploited by terror organizations," according to the Turkish leader.

For his part, the Pope spoke of poverty being one of the drivers of radicalization, but said he believed Christians and Muslims must work together to defeat the extremists' violence, to ensure Christianity was not driven from its birthplace in the Middle East.

Later, speaking to reporters on the plane as he returned home, the Pope said that he had told President Erdogan that it would be "wonderful" if all the Muslim leaders of the world - political, religious and academic - spoke up clearly and condemned the violence being carried out in the name of Islam.

Pope Francis said that would help the majority of Muslims, who were offended by the stereotype equating Islam with terrorism, because most would say that the Koran was a book of peace.

On this trip, the Pope himself spoke out with real passion against the killings and displacement of Christians, Yazidis and other religious minorities in the Middle East.

Christian reconciliation

Presdient Erdogan told the Pope he blames the West for the rise of Islamic fundamentalism

In that, he found a closer ally, external in Patriarch Bartholomew - the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church - whom some say is becoming a real friend, in a relationship that may ultimately help to heal the almost thousand year schism between these two main branches of Christianity that began here in what was Constantinople in 1054.

The Pope and the Patriarch issued a joint condemnation of the violence against Christians and others in the Middle East, and called for a constructive dialogue between Christianity and Islam based on mutual respect, saying people of all faiths could not remain indifferent to the suffering in Iraq and Syria.

"I think what he wants is an alliance of the faiths, of peace against terrorism and to give encouragement to Christians across the Middle East who are suffering, and in Turkey where there's a tiny beleaguered Christian population," says Austen Ivereigh, author of the biography, "The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope."

"Pope Francis is a master bridge-builder and he's great at building relationships across the divides of faith, of politics and of culture, and I think what he wanted to do on this visit - and as Pope - is to construct those alliances, and build a new kind of a civilization in which we respect each others' differences and are all able to take part equally in society, in peace."

Ivereigh notes that as Bishop of Buenos Aires, the then Jorge Bergoglio built genuine friendships with Jewish and Muslim leaders, as well as with other Christians.

"Those were deep relationships, which paid off particularly in moments of crisis," says Ivereigh.

"I think here he is again building relationships that are really loving, trusting relationships which, as the situation in the Middle East gets more tense, can be drawn on for the sake of peace.

"Action, not words - that's what the Pope is after."

Inter-faith relations

At one Catholic church in the centre of Istanbul, which bears a poster of the Pope and the Patriarch, the congregation is reluctant to speak to journalists.

The priest explains that some are converts from Islam, while others worry about discrimination.

So what are relations like between Turkey's majority Muslims and its religious minorities?

Turkey is an overwhelmingly Muslim country

"There is no problem in terms of practicing their religion, but there is historical baggage by which some religious activity is perceived to be suspicious," says Prof Dr Ilter Turan, emeritus professor of international relations at Bilgi University in Istanbul.

"Missionary activity was responsible for some of the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, which means the government looks with suspicion on proselytizing.

"I don't think it's so much that Christians in Turkey are under threat as feeling that they are marginal to society.

"It's only recently that the native Christian populations have begun once again to aspire to holding public office.

"At the late stages of the Ottoman Empire, that was normal and that only began to change after the First World War. So it seems that we are back to a period of restoration."

Refugee tensions

Of far greater concern to Turks, he says, is what is happening to the country as a result of the number of refugees coming in.

"Turkey is trying to cope, with a lot of effort and sacrifice, and unfortunately I think the international community is more generous in offering wisdom than offering support," he says.

The professor also believes that many in Turkey will support Mr Erdogan giving the Pope his views on Islamophobia in Europe.

"One must also examine how Muslims are treated in host societies in Europe, and in almost all (European) societies, the construction of a mosque becomes a major political issue, and is sometimes not allowed.

"And in many western societies, there is a rather strong anti-Islamic streak that is becoming more manifest as nationalistic parties receive more support there."

- Published28 November 2014

- Published30 November 2014

- Published27 November 2014

- Published28 October 2022