Cloughjordan eco-village makes slow progress due to economic downturn

- Published

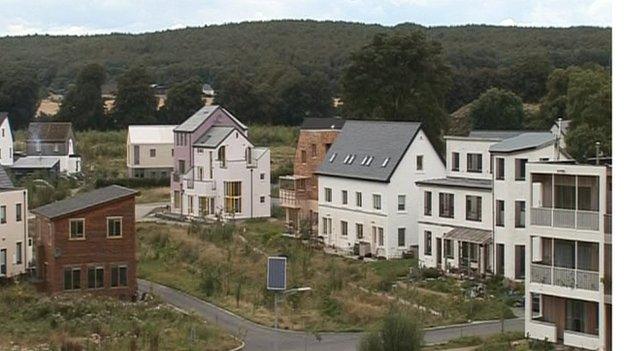

Cloughjordan eco-village displays a diversity of house styles

Five years ago I visited Ireland's first eco-village at Cloughjordan in County Tipperary and I recently returned to see how the experiment has developed.

The town was once known as Little Belfast because of the two Protestant churches on its main street.

The entrance to the eco-village with its solar panels and wood-fired community hot-water system is on the same road.

When I first visited here, individual, multi-coloured, timber-framed, well-insulated houses were going up, just as the Irish economy was crashing down.

Gearoid Ó Foighil, a resident and chairman of the local community development committee, admits the timing could have been better.

"The collapse of the so-called Celtic Tiger has dried up a lot of funds for people available to build," he says.

"There's a constant stream of interest and there are a few builds in the pipeline but the building rate, while ongoing, has slowed down quite a lot."

Site prices

The 68-acre eco-village has 130 sites; 86 have now been sold with 50 households now living there.

Five years ago the average site price was €80,000; now it is half that.

Guitarist Peter Manley, who is originally from Downpatrick, County Down, is one of the residents along with his Russian wife, Tatiana, and two daughters.

He used to work for an investment bank in London before moving to France and then to Cloughjordan.

"Here the car is a visitor, it doesn't dominate the landscape, so the children are free to roam and have the type of childhood I had," he says.

He admits there are also some disadvantages to living in the eco-village.

"We have quite a lot of meetings to attend because we're managing the estate ourselves. Things that you would normally out-source to a utility company or the council are done by ourselves. So, there is a lot of community involvement but at times that can be a bit much, I think."

The residents grow vegetables in community polytunnels

Another resident, Una Johnston, believes there are far more plusses than minuses.

As a member of the community farm she says she gets access to quality fresh vegetables, fruit and meat.

She has also noticed another benefit.

"Heating costs are much lower too," she adds, with many residents saying they do not turn the heat on between March and the end of October.

There is a lot of international interest in the village.

While I was there, a bus of Taiwanese tourists with an interest in planning arrived unannounced to see for themselves.

Ethos is education

Had they been aware of it they could even have stayed in the eco-village's own hostel, run by Pa Finucane.

"Our ethos here is education. We want to promote the idea of sustainability. We have developed a model of sustainability here that we hope people will come to and take away what we have demonstrated here," he says.

Roughly a third of the 68-acre site is residential property, a third community woods and a third for growing food or farming.

There are also businesses where the message of sustainability is very important.

Anthony Kelly runs a fabrication laboratory, a fab-lab, where he says businesses can manufacture just about anything.

"They don't have to travel long distances to make something; they can come here," he says, to do research and prototype their product and then "perhaps manufacture it abroad or wherever. Or, if it's a suitable product we can do some of the manufacturing for them here."

Local grains

Joe Fitzmaurice is an award-winning baker.

His grain is grown 500 metres from his bakery, and his oven is fuelled by wood from within a kilometre.

"That would show to me that we can have local grains and a local fuel supply for a local economy," he says.

Five years on, children now play where once there was just open space.

But the residents know - mainly because of the property crash - their vision of the eco-village has yet to be fully realised, despite the undoubted progress they have made so far.