Greece presidency vote raises fears of political turmoil

- Published

Greece's unpopular government has continued to attract widespread protests against austerity

When Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras proclaimed in mid-November that "Greece is back", it was for all the right reasons.

It had just been revealed that the country had exited a devastating five-year recession and his government was on the way towards negotiating an exit to the austerity-heavy bailout - devised by the eurozone and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) but hated by many Greeks.

A month on, "Greece is back" carries a completely different meaning. Mr Samaras has chosen to move forward a decisive presidential election, prompting concern among investors that this could soon lead to a change in government.

It sparked a reaction on markets reminiscent of the anxiety displayed when Greece headed to elections in May and June 2012 amid concerns about its euro membership.

Greece's stock exchange was down more than 20% last week and the yield on Greece's 10-year benchmark bond reached a recent high of more than 9%.

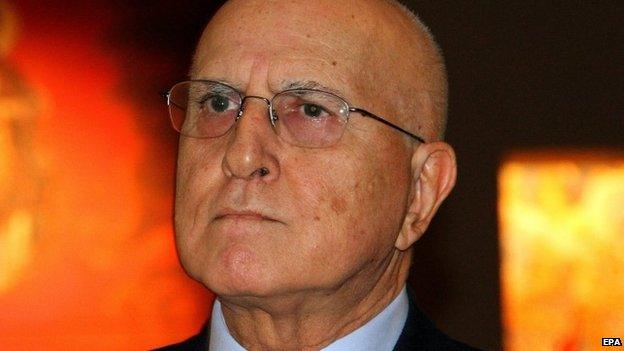

The Greek president has a largely ceremonial role, but if the government's candidate - ex-European commissioner Stavros Dimas - fails to attract the votes of at least 180 of 300 MPs by the time of the last of three ballots on December 29, national elections will be triggered.

Stavros Dimas, the government's candidate for president, is a veteran of EU politics

The first ballot in the presidential poll, when the winning candidate will need 200 votes, is on Wednesday. But with no individual likely to attract enough votes, polling will move forward to a second round on 23 December.

But because the second round threshold is also 200 votes, a third round is likely to then take place on 29 December with a final threshold of 180 votes - but that will still be difficult for the government to achieve.

"It's unlikely this Parliament will elect a president," says Nikolas Voulelis, the editor of the left-leaning Efimerida ton Syntakton daily. "If the government gets less than 165 to 170 in the first ballot, it will be very difficult for them to reach 180 by the final vote."

Opinion polls suggest that anti-austerity Syriza, led by 40-year-old Alexis Tsipras, would win any subsequent national election. The left-wing party wants the eurozone to cancel a substantial part of Greece's debt, which is expected to reach almost 178% of GDP this year.

Alexis Tsipras, leader of leftist party Syriza, has shaken up Greek politics

Greece's partners have so far shown a reluctance to discuss a so-called haircut of public debt, insisting it is sustainable. There are concerns a Syriza government would clash with other eurozone countries and European institutions to such an extent that it could even put Greece's place in the single currency at risk.

"The market negativity is a response to the political risk of an expected Syriza rise to government and the uncertainty regarding its true policy intentions, the continuity of economic adjustment, and the risk of a standoff with the troika," says George Pagoulatos, a professor at Athens University of Economics & Business (AUEB), who believes investors are currently overlooking the adjustment that has taken place in Greece over the past few years.

Scars

While Greece appears to have gone from the heaven of economic growth to the hell of political instability in just a few weeks, the reality is that the country is dogged by serious underlying problems.

The Greek economy is expected to grow by 0.6% this year but it has contracted by more than 20% since the crisis began.

The depression has left economic and social scars that will need time, and a convincing recovery, to heal. The most obvious problem is that despite edging down this year, the unemployment rate is still at 25.7%. In addition, almost three-quarters of Greeks without jobs are long-term unemployed, or those who have been out of work for more than a year. For those lucky enough to be working, wages have fallen by an average of almost 25% since 2010.

Supporters of the extreme right Golden Dawn party, which has attracted support during the crisis

This is taking a toll on Greek society. The percentage of Greeks at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2013 rose to 35.7% from 27.7% in 2010. Many Greeks have grown immune to talk of a recovery. A recent Pew Research Survey indicated only 19% of Greeks thought the economic situation would improve in the next 12 months, while 53% saw it getting worse.

Greece's traditionally dominant parties, centre-right New Democracy and centre-left Pasok, have suffered in this toxic climate. Blamed for causing the crisis and reviled by many for implementing the measures demanded by the EU and the IMF as part of Greece's combined bailouts worth €240bn (£190bn), the coalition partners have seen votes and MPs drift further to the left and right.

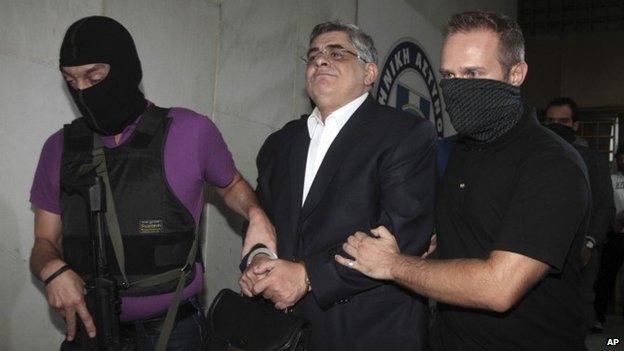

Nikos Michaloliakos, leader of the extreme far-right Golden Dawn party, was arrested in September 2013

Greek politics has become fragmented, with around 20 new parties being created since the June 2012 elections alone.

Neo-Nazi Golden Dawn is one of the parties that has benefited from this realignment, winning 18 seats in parliament two years ago. The extremist party's rise has been checked in recent months due to a judicial investigation into its activities following the murder of rapper Pavlos Fyssas in Athens 15 months ago. Seven of its MPs, including leader Nikos Michaloliakos, are in pre-trial custody and two of its deputies have quit the party.

Five years ago, Syriza - a loose association of hard-left factions - gained less than 5% in national elections. But as the crisis has worn on, it has become the leading domestic and European critic of the austerity policies applied in Greece, which have turned a public deficit of 15.4% of GDP in 2009 into a primary surplus of 0.8% last year.

The Athens stock exchange, where traders have endured tough economic conditions

In May, Syriza won the EU elections in Greece. With the possibility of a win in national elections looming, Mr Tsipras is trying to present himself as a reasonable choice who will cultivate relations with Greece's lenders, not push Greece out of the eurozone.

But Syriza still has fundamental differences with the so-called troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank and IMF, about how to resuscitate Greece's economy.

Investment fears

Alexis Tsipras has promised to raise Greece's minimum wage back to €751 per month, increase pensions and create a €5bn stimulus package to help create jobs. Syriza argues that Greece's main problem is a lack of demand, whereas the troika insists that the weakness is on the supply side, which can only be fixed by structural reforms.

"A demand stimulus would be a short term fix much of which would be directed to imports," says George Pagoulatos, who served as an adviser to Greece's interim Prime Minister Lucas Papademos in 2012. "Greece needs a more export-oriented growth model, through a combination of supply-side reforms and well-targeted investment."

Investors are wary of Syriza coming to power because there is virtually no time to resolve differences between these two divergent views.

The eurozone agreed this month to extend Greece's bailout until the end of February and then provide a precautionary credit line to help it tap bond markets if a final set of structural changes are agreed.

Antonis Samaras's New Democracy party has taken the blame for many of Greece's problems

Without a new agreement, Greece risks being left without a safety net to protect it from high yields on the international bond markets from March onwards, when it will have to cover a funding gap estimated to be more than €12bn.

However it is far from certain we will even get to that point. A failure to elect a president would lead to snap parliamentary elections, possibly on 25 January or 1 February, but opinion polls suggest that it is unlikely Syriza would win an outright majority.

This would leave Alexis Tsipras looking for coalition partners when no obvious alliances are available. His options would include the shrinking right-wing anti-bailout party Independent Greeks, the centrist and inexperienced To Potami (The River) and Pasok, the junior partner in the current government which Syriza has spent the last two years lambasting.

There is a real prospect that if snap elections take place early next year they may not lead to a government being formed, culminating in a second round of polls the following month. If unlikely political alliances do lead to the creation of a new administration, it will be under intense pressure from its first day in office. The odds on its long term survival are low.

Greece is definitely back. In fact, it never really went away.

- Published16 December 2014

- Published15 December 2014

- Published9 December 2014

- Published27 November 2012