Paris attack highlights Europe's struggle with Islamism

- Published

The attack on the office of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo left 12 people dead

In the heart of Europe in 2015, the killing of cartoonists and journalists for allegedly insulting God still comes as a shock, despite the rising number of such attacks in recent years.

In rational, post-Enlightenment Europe, religion has long since been relegated to a safe space, with Judaism and Christianity the safe targets of satire in secular western societies.

Not so Islam. The battle within Islam itself between Sunni and Shia, so evident in the wars of the Middle East, and the fight between extremist interpretations of Islam such as those of Islamic State and Muslims who wish to practice their religion in peace, is now being played out on the streets of Europe with potentially devastating consequences for social cohesion.

These latest shootings may be the work of "lone wolves" but their consequences will ripple across Europe and provoke much soul-searching about the failure of integration over the past decades.

Immigrant communities are already being viewed with increasing suspicion in both France and Germany, with their significant Muslim populations, and even in the UK.

France saw a series of "lone wolf" attacks before Christmas

France has the largest Muslim population in Europe, some five million or 7.5% of the population, compared with Germany's four million or 5% of the population, and the UK's three million, also 5% of the population.

In all three, mainstream political parties are being forced to confront popular discontent over levels of immigration and the apparent desire of some younger, often disaffected children or grandchildren of immigrant families not to conform to western, liberal lifestyles - including traditions of religious tolerance and free speech.

In the UK, that unease has largely played out on the public stage in a more peaceable manner, in the debate over "British values" and the recent Trojan horse schools affair.

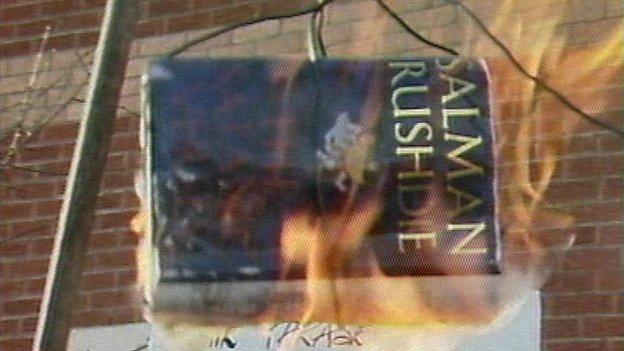

The fatwa against the writer Salman Rushdie over 20 years ago following the publication of The Satanic Verses, forcing him into hiding for several years, was perhaps the first time the issue impinged on British consciousness, though the attacks of 7/7 were a reminder that extremist violence could also hit the heart of the UK.

However, France has already seen much more violence on its streets carried out in the name of religion over the past decades, although it has tried to write off most of its recent "lone wolf" attacks as the acts of mentally-unhinged individuals.

UK protesters burned copies of Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses after a fatwa was issued against him

But some in its Jewish community have responded to increasing anti-Semitism and the killing of Jews in France and Belgium by Islamist extremists by emigrating to Israel and elsewhere.

Recent physical attacks on synagogues and Jews in the suburbs of Paris, where Jews and Muslims often live side by side in poorer areas such as Sarcelles, only exacerbated fears that the violence in the name of religion that grips parts of Africa and the Middle East, and which so many flee to Europe to escape, has followed them here.

Germany, too, has seen a rising surge of anti-Islam sentiment in its cities, with worries about young radicalised Muslims moving from a concern confined to far right and neo-Nazi parties into the mainstream, as seen in the recent popularity of the Pegida movement, which campaigns against the "Islamisation" of Europe.

Both political and religious leaders in Germany have spoken out against the movement, and counter-marches have been held, but Pegida's fears have brought thousands onto the streets.

Thousands of Germans have rallied in support of an "anti-Islamisation" group

The killings at Charlie Hebdo are a deeply unwelcome reminder to the west that for some, mainly young radicalised men, their fundamentalist interpretation of their religion matters enough to kill those who offend it.

As a result, across western Europe, liberally-minded societies are beginning to divide over how best to deal with radical Islamism and its impact on their countries, while governments agonise over the potential for a backlash against Muslims living in Europe.

Today, mainstream Muslim organisations in the UK and France have unequivocally condemned the killings, saying that terrorism is an affront to Islam.

But the potential backlash, including support for far right parties and groups, may well hurt ordinary Muslims more than anyone else, leaving the authorities and religious leaders in western Europe wondering how to confront violence in the name of religion without victimizing minorities or being accused of 'Islamophobia'.