Charlie Hebdo: Attacks carry extra resonance in France

- Published

Many see the attacks as a direct assault on the French Republic

Willem Holtrop sits in the Cafe de la Liberte, nursing a small glass of white wine.

He is one of the luckiest men in the world. He escaped the massacre at Charlie Hebdo because he doesn't like meetings.

Before we switch on the recorder he warns me: "I don't talk much. I drink and draw."

Willem, external, a Dutchman who has lived in Paris since 1968, manages, at 74, to be both cheeky and lugubrious.

With long white hair and matching droopy moustache, he has been a cartoonist with Charlie Hebdo, external before it was even called by that name.

He describes what he has drawn for this week's special edition.

"High clerics from all religions, imams, the Pope and they are all - 'Je suis Charlie', with a little sticker on their breast, and the title is 'Our new friends'.

"But it is much worse than that - all the extreme-right people are very happy with this. They are all hypocrites."

This is, of course, pure Charlie. There is more than a whiff of the Parisian street revolutionary about its humour - a desire to chuck a paving stone at the establishment - in outrage, and, yes, in sheer devilment.

But doesn't he want everybody to stand with Charlie, I ask.

"No, of course not. Not all those bastards. They are nothing to do with us. They never liked Charlie, they are our victims."

He has a point. Under the simple, emotive assertion of solidarity "Je suis Charlie" lies the awkward question: "Who is Charlie?"

Secular society

You don't have to listen too hard to discover that beneath the well-intentioned harmony there is discord, a cacophony of meaning.

Being Charlie might mean freedom of speech or cultural war, enlightenment values or patriotism.

But it is certain that the defiant solidarity on display in the streets of Paris has a very French accent. In Britain these massacres might have been seen as an assault on British values, in the US on freedom itself. Here it is the French Republic that is said to be under attack.

And that is true because it is a republic almost defined by secularism.

The burka is banned in France

In France the burka is banned and blasphemy laws, external were abolished during the Revolution - the clash of the reactionary priest and the rational schoolmaster the stuff of many a novel.

Prof Andrew Hussey, of the University of London, based in Paris, explains the concept of "laicite".

"It is a kind of aggressive secularism. It was originally introduced to police the power of the Catholic Church at the end of the 19th Century. It's not about Islam, but about religious authority versus political authority.

"It does attack people's identity - it does undermine them - it does make them feel alienated and angry.

"But what we've found this week is that Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite, external is not just an empty slogan.

"French people, and French Muslims I've been speaking to, have all been talking about La Republique. It is an abstract concept that plays out in everyday life here. It is your identity as a French person, whatever your creed or colour. And that's what was attacked."

Lack of multiculturalism

I think this is an essential point. While France may be home to many cultures, it does not celebrate multiculturalism.

Andrew Hussey told me that France can't negotiate with Islamists, violent or not.

"The Republic sees itself as an umbrella, above all of that.

"It cannot negotiate with the politics of identity. In the Anglo-American world we have a politics of identity - you could be gay, you could be black, all of these kind of things which have a political value, but in France we are all equal, whether you like it or not, and that is where the tension comes from."

The tension, the discontent, is most obvious in the banlieues.

The word, which in medieval times simply meant a place a few hours' walk outside the city where a lord held sway, is often translated as suburb - but both are equally misleading.

The connotation is more like "sink estate", with the suggestion of high levels of immigration, unemployment and crime.

I went to Gennevilliers, external where the murderous Kouachi brothers lived and worshipped most recently. It doesn't seem that bad a place.

There are a few derelict remnants of an older France; the rather picturesque, shuttered and shut "Cafe du bon coin" nestled among pastel-shaded, boxy flats, in the centre of town, and high-rise blocks on the outskirts.

A smart, new-looking library is decorated with a slogan declaring that the inhabitants are against barbarism and for freedom of expression.

No-one disagrees with that at the mosque, where they are both slightly wary and definitely weary of the media attention.

Mosque President Mohammed Benali says he didn't really know the brothers but the elder was always polite, never violent, and the only trouble they had with the younger was when he argued with the imam who was encouraging people to vote.

He says they do try to counter radicalism, but have to do more.

Made into targets

Outside I speak to three men, one in traditional dress and a big parka jacket, another in a sweatshirt and trousers, the other in a mixture of the two.

One journalist who has written a sophisticated account, external of the area found he was greeted with sullen shrugs from the youth, but these men, I would guess in their twenties and thirties, although initially wary, are keen to put their point of view.

Thousands have expressed solidarity with the victims of the Charlie Hebdo massacre

They say the massacre makes them targets too, and has poisoned the atmosphere.

"In 24 hours it changed. I'm a bus driver. People used to come on to the bus and smile, especially old Parisians. People would say what a nice beard.

"Now the same beard - they look at me strangely. Now, for them, even saying hello is difficult."

Another adds: "We're always being attacked from everywhere - just look around.

"I'm scared for my children, and my wife. They may be attacked by skinheads, for example. But am I scared of life? Things always happen."

A third says: "Even children are terrorised. After my six-year-old son's school did the minute's silence, he asked me, 'Dad, are the terrorists going to come and kill us?'

"And they asked the only Arab kid, 'Why are you doing it?' And he was beaten up."

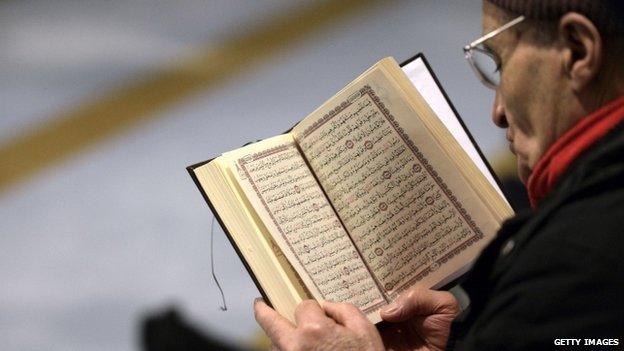

At a different mosque, this one on an industrial estate north-east of Paris, in a bland, undecorated office block, I ask one of the leaders of France's Muslims why some young men turn to violence in the name of Islam.

The Union of Islamic Organisations in France is an umbrella group. For 17 years Lhaj Thami Brez, external was its president and he is now its special envoy.

"Maybe it's something to do with the injustices happening across the world - in Palestine, Iraq, Syria and Libya - not to say that any of this justifies it.

"There is a connection with the suffering of young people here in France, and France too must play its part.

"It's more than police mistreatment, for example - it's multidimensional: social, cultural and economic.

"And we need to promulgate a better understanding of Islam - the practice, the simplicity, the recognition of the other, and capacity to live with those who are different."

Far-right opportunity

Many think this crisis will see a rise in the hard-right National Front (FN), and claim they are exploiting the crisis.

I asked Ludovic de Danne, one of the most senior advisers to FN leader Marine Le Pen, how he would answer this.

The attacks have galvanised a sense of French patriotism

"People in France are rising against societal collapse and barbarism. This massacre is probably the result of several things that have been happening in our country, and other places, for decades.

"We see there has been an educational failure because of a liberal system that couldn't integrate immigrants' children.

"And of course because of the uncontrolled rise of mass immigration and the rise of communitarianism [identity politics] where the French authorities were quickly seen as an enemy, and where socialists and communists used, and were used by, immigrants.

"Now we can see radical Islam, partly funded by foreign powers, taking over.

"As a former colonial power the elites didn't understand that patriotism was needed to keep this country united.

"And last but not least because Muslim countries have been humiliated because of the destruction of secular nationalist regimes from Syria to Libya and that has unleashed an evil force called Islamism."

In the Paris Museum of the Arab World there's an intriguing installation - interlocking cogs turn steadily - machine parts made of Arabic inscription and decoration. Mounir Fatmi's, external "Les Temps modernes, une histoire de la machine, external".

Past and present

Talking to Prof Hussey I get a similar sense of a very complex intermeshing of France's past and present that is much more awkward than the post-traumatic determined pride of the moment.

I ask him what is to me the key, and probably impossible to answer, question - why are young men radicalised?

He talks of the strut and swagger, the way the killers behaved as if they were in an action film.

Some French Muslims fear negative consequences

"They are speaking to a public, to an audience, a very small minority of dangerous kids in the banlieues who see themselves as superheroes.

"One of the problems the authorities here have is that they see themselves as fighting a cosmic war, fighting for God, a sort of metaphysical, theological politics.

"How does post-enlightenment Paris negotiate with that?

"Radicalisation is a process, like all revolutions, like the French Revolution. There are conditions that create the process, what the French call 'le passage a l'acte', how you get to the act, and often it is to do with atmosphere.

"I wouldn't make the argument that social exclusion, and bad urbanism, lead to Islamic violence because that is reductive and simply not true.

"But what you do have is over the years a matrix of complicated circumstances, which include social exclusion, the legacy of colonialism, the unfinished business in North Africa and 'double binds', a love-hate relationship between the Muslim population and French values, all of which create the circumstances where people who are full of hate and anger can find themselves manipulated and used for political ends by extremists."

Special significance

It is obviously true that these dreadful attacks could have happened in the UK or the US, but the fact they happened in France imparts a special meaning - in part because the Republic insists on its primacy over religion.

But it is not only that. France's colonial history is no more blood-soaked than Britain's - but the particular history of France in North Africa encapsulates a problem.

There were many opportunities to extricate the country from the unwise colonial adventure - but there were always balancing reasons not to do so until very late in the day.

With each iteration the situation gets less easy to solve, the gap grows wider, the West's perceived need to intervene gets more pressing and the violence, on both sides, becomes more horrific as the shocking psychodrama plays out.