Greek elections: What now for the euro?

- Published

The Syriza leader will face an immediate dilemma as Greece needs to negotiate a final bailout instalment

Anti-austerity party Syriza has won Greece's general election, pledging to renegotiate the enormous bailout with the country's international creditors.

It will now go into coalition with another anti-bailout party, the right-wing Independent Greeks, while the conservative New Democracy party of outgoing Prime Minister Antonis Samaras will form the next opposition.

Why did Syriza win?

Outside Greece, it might seem odd that voters have rejected the policies of the conservative New Democracy-led coalition, just as the country emerges from six years of deep recession.

But Greeks have been hit hard by cuts in jobs, public services and pensions and the apparent light at the end of the tunnel is far from obvious in the real economy.

Unemployment is still very high at 25.5%, external, especially among 25-35 year olds where it hits just under 50%, and recent emergency taxes, mainly on property, have further squeezed the middle class.

Syriza campaigned under the slogan, "Hope is on its way" and in his victory speech, leader Alexis Tsipras said: "Hope has made history."

Why choose a right-wing party as coalition partner?

It seems odd at first glance that the radical left Syriza would find common cause with a centre-right splinter party from one of Greece's main establishment parties, New Democracy.

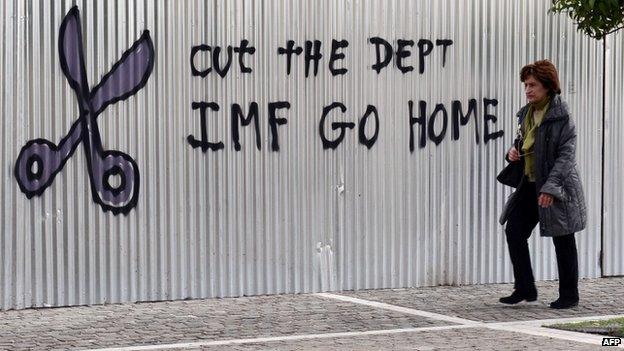

But both are vehemently anti-bailout and both have capitalised on the sense of anger and alienation felt by many Greeks towards the body of international creditors known as the troika - made up of the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Since 2010, Greece has borrowed nearly €240bn (£185bn; $278bn) , externalunder a debt restructuring (bailout) plan. But a final bailout tranche of €7.2bn still has to be negotiated and that could be one of the first big challenges for the new government.

Syriza wants to renegotiate Greece's debt, prompting fears that the country would have to leave the euro

That could create a big dilemma for Syriza, which has campaigned on a platform of writing off of a sizeable part of Greece's enormous debt, currently 175% of its gross domestic product. How will it persuade the eurozone to lend more when it wants to write off most of the debt?

Syriza's platform is simple, external: tackling Greece's cost-of-living crisis and restarting the economy. One of its key policies is raising minimum monthly salaries from €580 to €751.

But it also wants a "European debt conference" to create a sustainable repayment of the remaining debt after the larger part has been written off.

So what is the chance of a 'Grexit'?

The risk for Mr Tsipras is a collision course with Greece's creditors. They have been adamant that there will be no debt write-off although there might be some leeway over restructuring it.

Even though he insists that Greece should stay in the euro, and he has vowed to co-operate with fellow European leaders on finding a "fair and mutually beneficial solution", his victory speech was unequivocal.

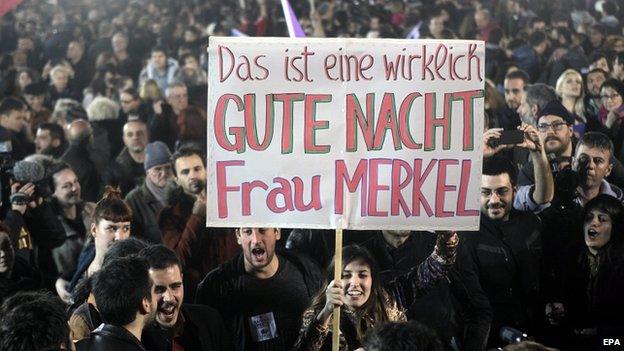

A poster held by Syriza supporters reads, "This is a really good night, Mrs Merkel"

The mandate of Greek voters had "put the troika in the past" and the "vicious circle of austerity" was over, he said.

So where does that leave Greece's international creditors?

It all looks like quite an impasse and Greece's future in the euro is not guaranteed, even though German Chancellor Angela Merkel has said she wants the country to remain "part of our story".

Perhaps the only hope of a deal might be in looking for ways of restructuring Greek debt.

Finnish Prime Minister Alexander Stubb is against writing any of it off but has offered extending the loan periods. And that opinion was backed up by Belgium's finance minister.

The biggest question mark is likely to be Germany's attitude. Mrs Merkel's spokesman said simply that Greece's commitments had to be kept.

Is there a risk of market meltdown?

The markets took the result largely in their stride, as it was widely predicted. The Athens stock exchange fared worst, slipping 4% before recovering. But these are early days.

ECB President Mario Draghi has announced a €1.1 trillion package, injecting cash into the eurozone

Partly, this was because the ECB has removed the threat of contagion that existed at the last Greek election in 2012, when the fear was that a Greek default could spread to Spain and Italy.

And it went further in recent days by announcing a programme of bond-buying worth €60bn (£44,5bn; $67bn) per month which may shield other eurozone economies.

Market analysts believe some sort of deal may be forthcoming, with Syriza proposing a six-month pause on the bailout programme.

But the question remains: how will a Syriza-led government handle its pending debt obligations of €4bn over the next two months, and more than €6bn of government bonds expiring by the end of the summer?

The total for Greece to repay this year is about €20bn, according to the Greek finance ministry (see the top chart on page four of this document, external).

The expiry of the current bailout programme in a month's time could cause liquidity problems for Greek banks, says Raoul Ruparel of the Open Europe think-tank. Currently they can use Greek government bonds as collateral to get cash from the ECB.

Will Syriza's victory have a knock-on effect elsewhere in Europe?

Pablo Iglesias of Podemos has become a close ally of Mr Tsipras

UK Prime Minister David Cameron believes it will "increase economic uncertainty across Europe" but the change in Greece could have even greater ramifications in EU countries where anti-establishment parties are on the rise.

Spain's Podemos party is already leading in opinion polls with a similar anti-austerity platform and Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is eyeing Syriza's success warily ahead of elections later this year.

In the UK itself, Nigel Farage's UKIP could benefit as could the anti-euro party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Another party celebrating Syriza's victory was Germany's far-left Die Linke which since late last year has led a coalition in the eastern state of Thuringia.

- Published26 January 2015

- Published16 December 2014

- Published16 January 2015

- Published15 January 2015

- Published28 June 2023