Auschwitz anniversary: The survivor who brought the Holocaust to life

- Published

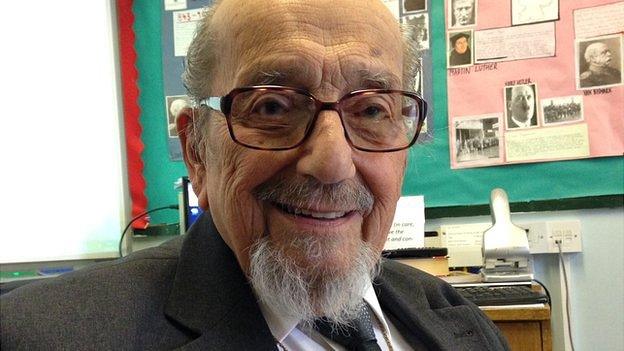

Thomas Geve's picture entitled "We are 'Organising'", showing prisoners using poles to try to gather food from hard-to-reach places in Auschwitz

In the Spring of 1945 a teenager called Thomas Geve had a remarkable story to tell.

He had survived for two years in the death camps at the heart of the Nazi Holocaust - Auschwitz first, then the westward forced march as the Germans retreated from the Russian advance, and finally Buchenwald.

His mother died in Auschwitz but his father, who had been separated from the family in the chaotic months as Europe slid into war in 1939, had survived in England.

So Thomas - newly liberated - took a box of coloured pencil stumps and began to draw.

He created 82 simple pictures that told the story of what life and death in the camps had been like.

Thomas Geve survived two years in Auschwitz. Here he depicts how prisoners were disinfected in the camp.

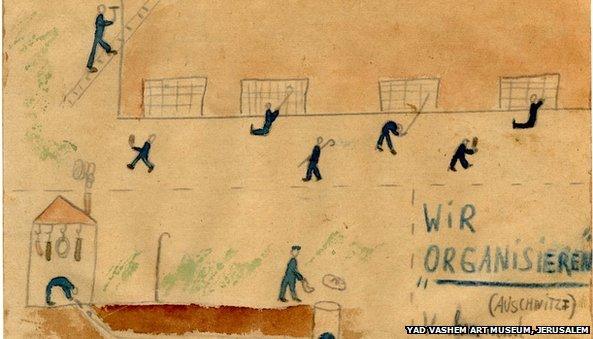

In this picture, prisoners in Auschwitz are shown undergoing inspection by camp guards.

After Auschwitz, Thomas was interned in Buchenwald until its liberation by US soldiers, as depicted here

The style is simple and childish - like a kind of dystopian LS Lowry - but the pictures were created while the hellish life of the camps was still fresh in his mind.

With his mother killed, Thomas wanted to tell his father about life in the camps; we will never know what it must have been like for his father to know that his teenage son had lived through the nightmare of the Holocaust when he himself had not.

Thomas knew and understood a world of gas chambers and crematoria, of brutal SS officers and Jewish "kapos" recruited to serve under them, a world of roll calls that stretched on for hours in the freezing mud, of prisoners beaten or starved or gassed to death, of people abandoning all hope before finally losing the will to live.

Some of his illustrations are extraordinary.

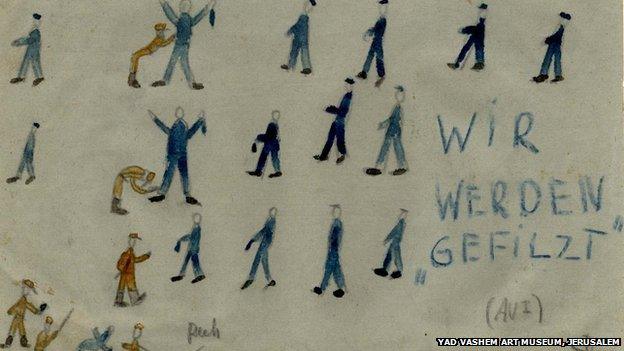

There is an "Auschwitzer ABC" which looks like the kind of teaching aid you use to teach young children the alphabet but which is instead a point-by-point guide to how the camp worked.

ABC of Auschwitz

Thomas Geve's Auschwitzer ABC

Clearly impressed, Thomas' father went to see a well-known publisher in London, presumably convinced that the unique collection of coloured illustrations of life in Auschwitz was both a priceless historical document and a story that needed to be told to others as it was to him.

He was in for a shock.

.jpg)

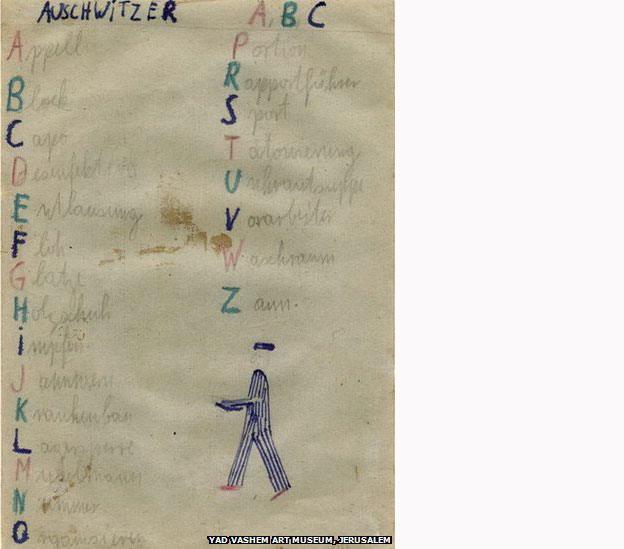

Thomas Geve, whose drawings illuminated some of the darkest chapters of Jewish suffering under the Nazis

"Your sonny-boy there is no Picasso," the publisher told him. "Do you have any idea how much it would cost to print a book in seven different colours of ink? It can't be done."

Thomas himself sensed even then that the decision was not just about the economics of publishing.

The world was weary of the war and the years of grinding misery, austerity and chaos which followed and which we sometimes now forget.

And as he puts it himself: "People weren't ready to be told how the world worked by a 13-year-old boy."

Camps memoir

So as we mark the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and prepare to listen to the stories of the survivors, it is worth remembering that there was a time - not so long ago - when no-one was listening.

Thomas resolved to write his story down. He admits the first draft was a little crude - after all, he had never written anything before and had missed years of schooling.

A picture entitled Hurrah the FREEDOM, drawn in Buchenwald Displaced Persons camp in 1945

But eventually - with a little help - he produced a memoir of camp life which in English is called Youth in Chains.

It was then, after spending a few years in England, that he decided he needed a pen-name.

He liked the works of PG Wodehouse and decided to adopted a Germanised version of the name of Bertie Wooster's imperturbable butler.

However unlikely it may seem, the author of this startling bleak vision of life in Auschwitz bears the name of Jeeves.

Witness to history

Thomas migrated to Israel and made a new life, in common with many other Jews who had survived the Holocaust. He became an engineer and has an engineer's love of the concrete and the factual.

It makes him a remarkable first-hand witness to history.

Listen: Restored pre-WW2 cello plays a version of the Jewish Kol Nidre melody

He was a teenage boy and his growing interest in girls is charted against the darkening atmosphere as the Germans sense the Russians getting closer.

And there is the story of how prisoners from different countries managed to learn enough of a common language to talk - apart from anything else Thomas was a German Jew surrounded by lots of Poles, Ukrainians and Russians who had, as he points out, two reasons to hate him.

But it took long years to get that book published - even though it is a striking document and a compelling read.

Thomas makes light of all that now - he jokes that eight publishers went bankrupt after publishing the memoir - but you sense he is glad to be listened to at last.

'Bad dreams'

He tells his story in German schools and patiently answers the kind of questions that young children like to ask.

They want to know what sort of toys he had as a child before the Nazis swept away his happy middle-class life in Stettin, now Szczecin in Poland (he particularly liked a model railway set).

And of course they want to know if he has nightmares about the camps. He does not, he told me - but he sometimes has bad dreams about being stuck in a city somewhere in Europe and not knowing how to get to the railway station, or what currency to use.

On this 70th anniversary of the liberation there will be plenty of opportunities to reflect on the Holocaust. Notable events will include a concert in Germany featuring recovered instruments, including at least one violin known to have been played in the camp orchestra at Auschwitz.

But this may be the last significant anniversary where there will be many survivors around - including some who will travel back to Poland - to tell their own stories.

The world missed many opportunities to listen to people like Thomas Geve in the past - it should not miss this one.

- Published26 January 2015

- Published19 January 2015

- Published25 January 2015