Auschwitz message still resonates today

- Published

Snow adds to the sombre story told by Auschwitz

Snow has settled on the trees dotted across the camp at Auschwitz I.

A thick icing of white blankets the blocks where over 1,000 prisoners were crammed into each.

But nothing can disguise the horror of what happened here from 1940 to 1945.

Even the groups of schoolchildren trooping out of the dark and airless cells of punishment Block 11 are silent as they emerge - the only sound their footsteps crunching through the snow.

On Tuesday, though, Auschwitz II-Birkenau will ring out with the voices of those who survived this Nazi extermination camp, as 200 or so survivors gather to mark the 70th anniversary, external of its liberation by soldiers from the Red Army.

Theirs are the voices that the Nazis sought to stifle forever.

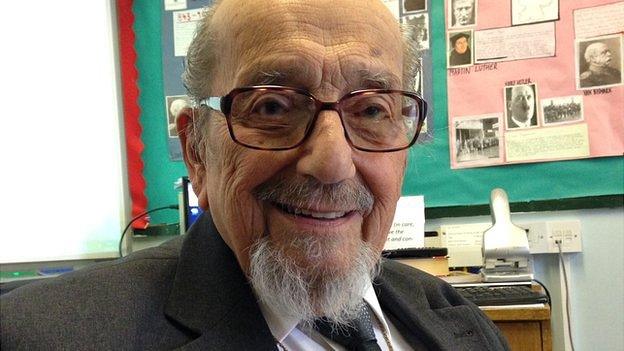

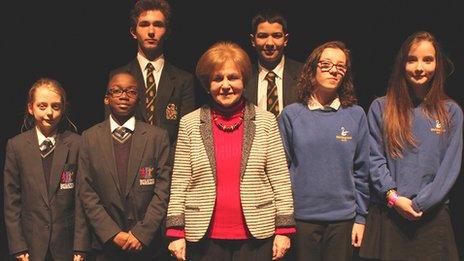

Although now in their 80s and even 90s, some feel compelled to return, to speak out on behalf of those who are no longer here - and to tell their story to a new generation, before it's too late.

Renee Salt, 85, from north London, is among them.

"For 50 years I didn't go back to Auschwitz.

"The first time I went was ten years ago. It was terribly difficult, but after that I was pleased that I went - I buried the ghosts.

"And since then, I've been going backwards and forwards.

"I'll do it for as long as I can. Why? There are still a lot of Holocaust deniers, the world over, and if we don't speak out, the world won't know what happened.

"I was one of the lucky ones, who survived when so many did not.

"And that's why we do it."

Awful reality

It is hard to deny the awful reality of the barracks at Auschwitz I, or the railway line that brought over a million people to their deaths at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, the extermination camp, 90% of them Jewish.

Prisoners' discarded shoes are on display

The camp first housed political prisoners from Poland, and captured soldiers from Russia.

Then, Jewish families from across Europe were transported here in cattle trucks as the Nazis tried to carry out the Final Solution - the annihilation of Europe's Jews.

A chart at the museum shows how all the Nazis' enemies imprisoned in the camp were given special badges to mark them out: yellow stars for the Jews, a pink triangle for gay prisoners, a purple triangle for Jehovah's witnesses, and many more marking out each minority in a hierarchy of human hell.

Even 70 years on, Auschwitz itself stands as mute but concrete testimony to man's inhumanity to man: a place where the very ground still feels contaminated by death on an industrial scale.

The museum was established in 1947 with the help and advice of some of its former prisoners, who fought to secure its future as a permanent memorial to those who did not survive, and a warning to future generations.

Struggle to stay open

However, the museum has struggled for many years to fund its work, and to secure the fabric of many of the buildings, which were never created to last.

The most powerful displays - of human hair shaved from prisoners' heads, or the crumpled leather of children's shoes - are also the most fragile and perishable.

The camp has been largely preserved

The museum's funding long came mainly from the Polish government, but as its workforce fought to cope with decay and the immense task of conservation, including the museum's vital archives, still used by relatives of the victims many years on, others have now stepped in to help.

Recently, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation, external has said it has almost reached its goal of raising an endowment of some $156m, thanks to donations from 34 countries including Germany, the US, Poland, Turkey and the Holy See, as well as private donors including Steven Spielberg's Righteous Persons Foundation.

A stable source of income should allow the museum, for the first time in its history, to plan for the long-term conservation of its almost 200 hectares of grounds and the 155 buildings and 300 ruins, plus its archives and collections.

The aim is to ensure that even 30 years from now, Auschwitz will be visible, accessible and comprehensible for the 1.5 million people who visit every year.

Renewed concerns

Auschwitz remains a potent symbol, even 70 years on, with the anniversary coming at a time of renewed worry for Jews in many countries in Europe where anti-Semitic attacks have been on the rise.

The main gate at the camp

After the killings of cartoonists, journalists and Jews in Paris by Islamist fundamentalists, and later revenge attacks on mosques and Muslims in France and elsewhere, the message of Auschwitz of "never again" strikes many gathering here today as as relevant and as necessary as ever.

And as societies across Europe grapple with immigration, and seek to define themselves and their values anew, asking their religious minorities to prove their loyalty to their country, the words embossed on the monument at Birkenau, "let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity" have a chilling resonance once again.

- Published27 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published19 January 2015

- Published25 January 2015