Charlie Hebdo attack: Teachers tell of classroom struggle

- Published

Here teachers in France tell the BBC about their struggles to assert the country's traditional values of free expression and secularism in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

Some have asked to remain anonymous so have only given their first names.

Xavier G, history and geography teacher in central Paris

The minute's silence went relatively well because we only had two incidents. The pupils involved showed reticence so they had a chat with the civics teachers.

The school was at the heart of the events, close to the Charlie Hebdo offices. One of my students heard the shots being fired by the Kouachi brothers. Many of our pupils skateboard in Place de la Republique. It all meant a lot to them. They needed to make sense what had happened.

We discussed the issues: it was the first act of war in Paris for a long time. We talked about caricatures, blasphemy, freedom of speech. A few loudmouths said: "They [Charlie Hebdo] were asking for it." We discussed this in class and some of them ultimately revised their opinion. So what we had was mostly blustering.

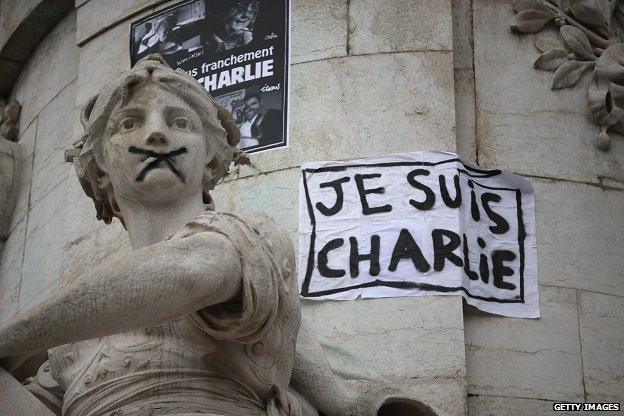

Banners adorn monuments in Place de la Republique after the unity march in Paris

Constance, literature teacher in Dijon, eastern France

It was very spontaneous. On the Thursday morning I saw some of my final-year students as I came in. They asked me for adhesive tape because they wanted to make banners. They took the initiative very quickly. They went to see the head teacher to get authorisation for their plan. They made a speech to younger students after the minute of silence on Friday, then demonstrated across the city, and of course took part in the main [unity] rally on Sunday.

Gabrielle Derameaux, literature teacher at the Lycee Buffon in central Paris

The initial reaction was one of unanimous revulsion among pupils. On the Thursday everyone agreed that you don't kill people because you are offended by drawings, regardless of your beliefs.

On the Friday, frictions started to creep in. Then there was the mass "Je suis Charlie" demonstration at the weekend. When the pupils returned to school on the Monday, the disruption began. Two pupils found conspiracy theories on the internet: The Kouachi brothers were innocent… Wasn't it strange that police had found the ID card left in the car? It was obviously a plot by intelligence services…

I asked what purpose there could be in killing people of various ethnicities and religions. They came back with the answer: "To sully Islam." I was surprised because those two boys of North African origin had never said that sort of thing. But they were defiant. I represented the official version, and they had access to a hidden truth.

Problems in the school system run deep. Courses on the Enlightenment, for instance, can be a problem. In a class last week I was analysing an article by Voltaire on religious fanaticism, which is on the national curriculum. As I was talking, the pupils were listening so intently that there was silence. Suddenly two of them made increasingly loud snoring noises that ended up covering my voice.

Secularism is not the only sensitive issue. It is also difficult to teach colonial wars. You will be challenged, some will whistle or hum to stop you talking. You will be accused of dishing out propaganda. I noticed an abrupt change in 2001, when I was teaching in an immigrant suburb. My students refused to observe a minute's silence for the victims of 9/11. The most radical among them started singing Hamas songs. I was a young teacher and did not know what to do.

Discipline is a big problem. When people talk in class and the teacher tells them to be quiet, a common retort is: "I'm not talking to you" - meaning you're interrupting my conversation. What plays against me is that I am a woman - some pupils will not respect me.

If I have two or three troublemakers per class here, I can only imagine what it must be like for my colleagues who have remained in deprived suburbs. Boosting civics courses and encouraging pupils to sing the Marseillaise (as the education minister suggested following 200 reported incidents during the minute's silence) does not go nearly far enough to tackle the underlying problems.

Iannis Roder, history teacher in Saint-Denis

When I heard pupils recycling conspiracy theories after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, it reminded me of 9/11. The very next day, on 12 September, a boy said in class that Jews were behind the attack. He knew this because there were no Jews in the twin towers at the time. I said: "You must be really smart! We still don't know the number of victims, but you already have the list, with their religion." Everybody laughed. The kid felt a bit silly and I defused the situation that way.

History teacher Iannis Roder teaches mostly Muslim pupils: "Just a minority of them were very sad about what occurred."

When I am confronted with that sort of thing I now use texts by Hitler, Stalin, Bin Laden and other classics of the conspiracy genre to show the similarities between their visions of the world: a hidden elite is pulling the strings - often the same people incidentally. And I show that such ideas have serious consequences: tens of millions of people killed in the case of Nazism and Stalinism.

It can be tricky teaching some subjects - such as the Holocaust, colonial wars, or the Middle East - but this is mostly a problem of teacher training. When a kid tells you a genocide has been committed by the French in Algeria or by the Israelis in Gaza, you have to refer to the official definition of a genocide and see whether its applies. You are going to be challenged: background knowledge and a good relationship with pupils are vital to meet that challenge.

Today teachers are competing with other sources of information - notably social networks and the internet. Teachers are no longer the ultimate source of knowledge. So you have to be extremely strong on learning in order to have authority. And if there is an emotional bond with the pupils, you can deliver any message.

Anne, literature teacher west of Paris

On the Thursday (a day after the Charlie Hebdo attack) I was shaken by what I had seen on TV. I spoke to the head teacher, who gave me permission to post a "Je suis Charlie" banner in my classroom. But he also said something that surprised me: he would not force teachers to enforce the minute's silence (declared by the education minister) on the Friday. He had anticipated problems - but I had not. I could not imagine that pupils would not observe a minute's silence.

Then I faced my class of 14 to 15-year-olds, with whom I have a wonderful relationship. I asked how they felt about the events of the previous day, without giving my own reaction. Their response hit me in the guts: "Miss, the journalists got what was coming to them"; "You should not mock the Prophet." Only the Muslim pupils spoke - about a third of the class. The others did not say a word. When they saw the tear on my face, they held back: they did not want to upset me.

Charlie Hebdo's publication of images of the Prophet Muhammad angered many Muslims around the world

In my younger class, they were even more virulent. "When you receive death threats you have to stop what you are doing," they said. On the Friday they all observed the minute's silence, but I did not feel it was out of respect for the victims - but out of respect for me. Some of my colleagues who do not have that sort of relationship with their pupils had problems; others did not observe it at all.

More recently, a boy mimicked the killings in a corridor, firing an imaginary Kalashnikov and shouting "Allahu Akbar" (God is great, in Arabic).

I thought the battle of secularism had been won, and that after several years in school they had absorbed all this. But I now realise that this is not the case. But I will not give up. I will continue to fight for my convictions. I am a daughter and granddaughter of teachers: secularism and the values of the Republic are in my genes. If there were more teachers like me - more teachers who believe in what they do and stop looking the other way, things would be better.