Greece's debt plans: What will happen if there's no deal?

- Published

Greece's finance minister says his country is a bankrupt state

Greece's new left-wing leaders are trying to persuade eurozone officials and governments to renegotiate the terms of their country's €240bn (£182bn) bailout.

They have already had a setback from the European Central Bank, which says it will stop accepting Greek government bonds in return for lending money to Greek banks.

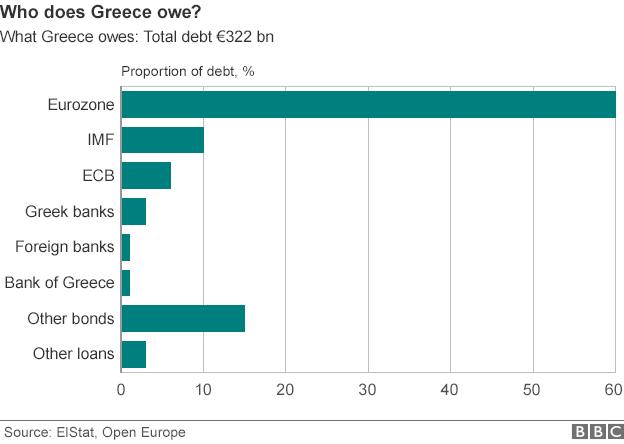

So what do we know so far about Greece's plans to cut its debt, which stands at more than €320bn, around 174% of Greece's economic output?

What happens when the EU's current loan programme ends?

Greece does not want to extend the programme or receive new payments under the existing programme, which ends on 28 February.

But it does want to receive the profits the European Central Bank (ECB) has made on buying Greek government bonds, government debt traded in the markets. This is money which has been promised to Greece but not yet handed over and is worth €1.9bn.

Hand in hand? Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (L) needs the backing of the European Commission

Greece will not run out of money straight away. The government says it can pay the bills until June when a payment to the ECB of €3.5bn is due on some of those bonds the ECB holds. Tax revenues are now enough to cover government spending apart from debt payments - it's called "primary surplus".

But the end of February could still be problematic. The ECB could cut back on the loans it and the national central bank in Athens make to Greek banks, if the government does not get an extension to the bailout programme. In view of the uncertainty, the ECB has already decided, external to stop accepting Greek government bonds as collateral for lending to banks.

Key dates for Greek government's diary

What if the ECB pulls the plug on Greek banks?

ECB money - called reserves - is one of the foundations of a banking system, so they always need it. But the banks need to borrow more now because deposits are being withdrawn. Private sector deposits at Greek banks fell by €4bn in December according to official figures and banking sources say they fell €11bn in January.

So far the ECB has taken steps that make it a bit harder and more expensive to borrow central bank money.

But if the ECB pulls the plug completely, that could lead to the banks failing. That in turn would mean a severe financial crisis in Greece. The government would then have to consider reintroducing the drachma or draconian restrictions on the movement of funds out of Greece. Most analysts think it won't come to that, but it is conceivable.

Can Greece find money elsewhere?

If the money from the ECB stops, Greek banks can get funds from the national central bank in the form of emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). But the ECB can veto that and has threatened to do so in the past, ahead of bailout agreements for Ireland and Cyprus.

It has not been spelled out in detail but reports suggest the Greek government would like payments on some of the debt to be linked to Greek economic growth - the more it grows, the more interest is paid. And then bonds held by the ECB would be replaced by "perpetual bonds". Regular interest would be paid indefinitely but they would never be repaid.

Greece's Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis is said to be looking for a four-month "bridging programme"

Greece's new leaders also want to use Treasury bills - short-term government bonds that do not pay interest until maturity - as a source of funds. The government wants the current €15bn cap on T-bills to be raised by €8bn. But the ECB is reluctant to allow this, according to the Financial Times., external

Reports in the Greek media, external also suggest the government might after all be willing to tap funds agreed as part of the controversial European bailout programme that have not yet been paid.

Meanwhile, there are reports that Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis wants a so-called called "bridging" programme - a four month period in which the ECB would continue to support the Greek banks while a fuller reform programme is developed.

What chance is there for an agreement between Greece and its lenders?

There are options that could ease the repayment burden - reducing interest rates and extending the repayment period or perhaps the debt swap envisaged by the government.

It is possible to argue, though not very convincingly, that it isn't really debt forgiveness, which makes it easier for Germany and others to accept. It has been done before for Greece.

The Greek government's financing proposals are part of wider plan presented to the eurozone finance ministers. Other elements include less stringent budget targets and a new set of economic reforms to be discussed with the Organisation for Economics Cooperation and Development.

Other eurozone finance ministers are very wary of such departures from the plans agreed with previous Greek governments.

Where does all this leave us?

There is a large number of different moving parts - political, financial and economic - and a great deal of uncertainty about what will emerge. None of the key players wants Greece to leave the euro, but it might just happen. One German expert said the probability of "Grexit" has climbed from virtually zero to 20%. In other words, still unlikely but certainly possible.

A lawyer at the ECB has suggested there is no legal basis, external for Greece being forced out of the euro. And if it were to leave the euro, under the law as it is, it would also have to leave the EU.

In practice, however, a country whose banks were cut off by the ECB would have little choice but to go back to its own currency or introduce capital controls.

Germans on the radical left back Greece, but most Germans fear paying the bill if Greece fails to pay its debts