Paris attacks: Prisons provide fertile ground for Islamists

- Published

For anyone trying to recruit people to the cause of radical Islam, a French jail would be an ideal place to start.

As many as 60% of France's 70,000 prisoners have Muslim origins, and their backgrounds and criminal records make many ripe for radicalisation.

"They have been broken by educational failure, family breakdown, and unemployment. They are very fragile people," says Missoum Chaoui, a Paris Muslim leader who has worked as prison chaplain for 17 years.

Among the French criminals believed to have turned to extremism while behind bars is Amedy Coulibaly, a man of Malian descent who shot dead a policewoman and four Jews in two of last month's three deadly attacks in the Paris area.

Missoum Chaoui has been a prison chaplain in the Paris area for 17 years

Coulibaly forged the links that would turn him into a jihadist while in jail for robbery in 2005.

At Fleury-Merogis prison, he later told police interrogators, he met one of France's most dangerous inmates, Djamel Beghal.

An al-Qaeda-linked militant, Beghal was then serving a 10-year sentence in Europe's largest prison for a plot to bomb the US embassy in Paris. Although Beghal was being kept in isolation, Coulibaly says he was able to befriend him.

Coulibaly was also introduced to another follower of Beghal, Cherif Kouachi. The three then met after their release.

Eventually Coulibaly, Cherif Kouachi and his brother Said co-ordinated the attacks that killed 17 people in January. The Kouachi brothers shot dead 12 people at Charlie Hebdo magazine, shouting "Allahu Akhbar".

Online recruitment

The justice ministry has warned against using Coulibaly's story to portray French jails as breeding grounds for militants. "No-one can really tell whether he was radicalised in prison or outside," ministry spokesman Pierre Rance says.

Mr Rance also points out that, of 167 people detained in France on terror charges and regarded as radical Islamists, only 15% had been incarcerated before.

Clearly, extremists gain more recruits through personal contact or online than in prisons.

Nevertheless, Justice Minister Christiane Taubira admitted after the attacks in January that radicalisation in detention was a "major issue".

It is also far from new. Over the past 20 years, a number of major attacks have been blamed on one-time petty criminals who found religion in French prisons.

Militants and French jails

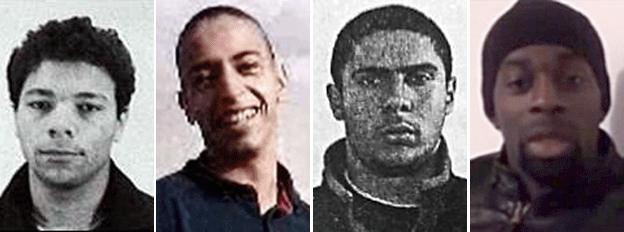

(L-R) Khaled Kelkal, Mohamed Merah, Mehdi Nemmouche and Amedy Coulibaly

Khaled Kelkal: Member of Algeria's GIA group; main suspect in 1995 attacks on France in which eight died; shot dead near Lyon. Petty thief who turned to Islam in jail in early 1990s

Mohamed Merah: Killed three soldiers, three Jewish children and a rabbi in 2012 shooting spree in Toulouse in southern France; said he turned to militant Islam while in jail for robbery; in 2010-2011 travelled to Afghanistan and Pakistan to train for jihad

Mehdi Nemmouche: French-Algerian accused of killing four people at Jewish Museum in Brussels in May 2014; reportedly radicalised while in jail for robbery; after release in 2012, spent year with Islamic State in Syria

Amedy Coulibaly: Murdered policewoman and four Jewish men in kosher supermarket in January 2015. In and out of jail for robbery and drug trafficking from age 17; met imprisoned militants Djamel Beghal and Cherif Kouachi in 2005

Early signs of radicalisation in prison may be difficult to spot, because they are those of a regular religious awakening - such as swapping Western clothes for an Islamic robe, refusing to watch TV, praying frequently, or demanding halal food.

Clearer clues may include refusal to undress for the collective shower, urging cellmates to take down pictures of women, or refusing to speak to guards.

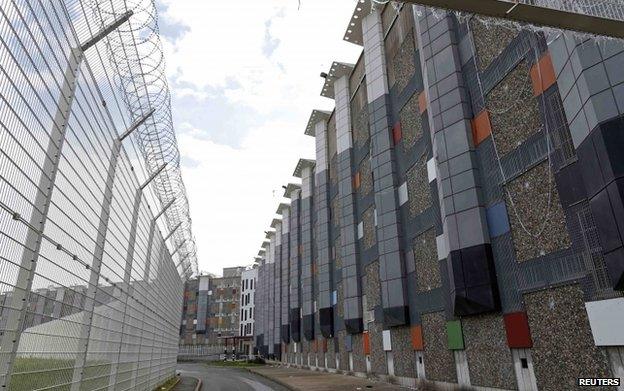

Amedy Coulibaly forged links with jihadists at Fleury-Merogis, Europe's largest prison

Karim Mokhtari, who spent six years in jail for armed robbery and now works with young offenders in prison, says he can tell who is becoming radicalised by their acute sense of victimhood.

"They say, 'the French never gave us a chance. They hate us. They are locking us up. These people are unbelievers. I do not have to apologise for what I have done because they shut me out'," he says.

In some cases, Mr Mokhtari says, this turns into talk of "fighting the infidels".

That message of grievance and "us against them" finds a ready audience in a prison.

"People are easy to indoctrinate because that is what they like to hear," says David Daems, a guard and spokesman for the main union of prison staff, FO-Penitentiaire.

It is not just Muslims who are susceptible, Mr Daems adds.

He once saw a detainee with no foreign ancestry turn into a fundamentalist before his very eyes: "First he converted, grew a beard and wore a robe; then his language became aggressive and he refused to speak to female staff. In the end he performed circumcision on himself."

Special wings

One aspect of prison life that provides prisoners with ample opportunity for proselytising others is the daily exercise break, when inmates are allowed to mill around freely in the courtyard.

Radical preachers sometimes use that time to call for collective prayer in defiance of prison rules, under which religious activity must be led by official chaplains in places set aside for worship.

An experiment at Fresnes prison to keep radical militants apart is now being replicated

But there is little authorities can do when a self-styled imam issues a wildcat call for prayer.

"The guards are unarmed and will never set foot in the courtyard during exercise time," says Mr Daems. "When you have 700-800 inmates walking around, it would be way too dangerous."

Prisoners who defy the collective prayer ban can face punishment.

Last month the justice ministry announced a plan to tackle radicalisation in jail, involving recruitment of more staff and significantly increasing the number of Muslim chaplains over three years.

But the headline measure is the construction of five special wings to house radicals convicted of terror offences.

This builds on an experiment conducted since September at Fresnes prison, south of Paris, where about 20 radicals singled out for their recruiting zeal are kept apart from others for all but a few supervised activities.

The trial, according to justice ministry spokesman Pierre Rance, yielded interesting results.

"Other inmates, notably Muslim, have returned to normal behaviour, notably with respect to showers and pictures in their cells. The atmosphere in the prison has changed completely."

Faint-hearted jihadists

But not everyone is convinced by the Fresnes experiment. The FO-penitentiaire union, which has accused successive governments of ignoring the problem for two decades, says the plan does not go far enough.

French guards do not venture in the courtyard during the daily exercise break

Union spokesman David Daems notes that it involves only those detained on terror charges whereas he believes a radical serving time for other offences can be just as dangerous.

"The problem of radicalisation is not being tackled in its entirety, both terrorist and non-terrorist," he says.

And there are varying degrees of radicalism, too. Activist Karim Mokhtari notes that many French youths have travelled to Syria or Iraq seeking heroic martyrdom, only to find that a jihadist's life is not all it is cracked up to be.

Would-be warriors have written home with complaints such as: "My iPod has stopped working. I want to go back!"

But once they come home, they are deemed to have committed a serious crime under France's anti-terror laws governing anyone returning home from a war zone.

And then, Mr Mokhtari says, if the faint-hearted are locked up with hardened fighters there is "even more radicalisation within the group".

"When you bring [militants] together you reinforce them. When you scatter them, you enable them to find new recruits," says criminologist Alain Bauer.

The challenge for a prison system trying to tackle radicalisation is that there is no easy answer.

Wednesday 7 January - Cherif and Said Kouachi shoot dead 11 people at Charlie Hebdo offices and kill police officer nearby

Thursday 8 January - Lone gunman Amedy Coulibaly shoots dead policewoman Clarissa Jean-Philippe and injures man in Montrouge, southern Paris.

Friday 9 January - Kouachi brothers killed in standoff at industrial building 35km (22 miles) from Paris. Coulibaly murders four Jewish hostages at kosher supermarket in eastern Paris - Yoav Hattab, Yohan Cohen, Philippe Braham and Francois-Michel Saada - before being shot dead by police.

- Published30 January 2015