Ukraine crisis: Poroshenko bruised by army retreat

- Published

Damage in Vihlehirsk, near Debaltseve, testifies to the intensity of the fighting

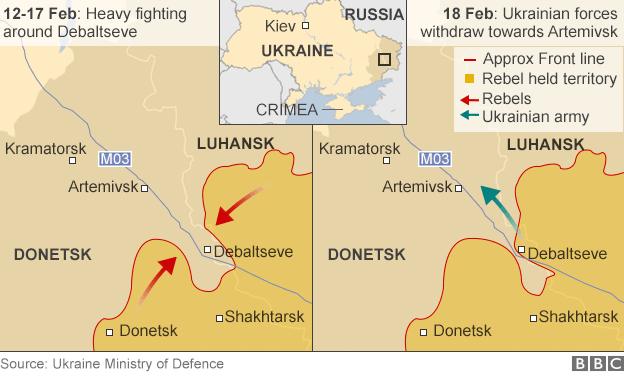

The question is not whether the fall of the strategically important road and rail hub of Debaltseve was a blow to Ukraine's political and military leaders. It was.

The question is how big the impact will be.

President Petro Poroshenko is portraying the retreat of thousands of Ukrainian government forces as an "orderly" tactical withdrawal. However, initial reports indicate it may have been just the opposite.

It is still possible that the retreat avoided a larger, more catastrophic defeat - something along the lines of the Ilovaysk debacle last summer, when Ukrainian forces were encircled by insurgents and possibly regular Russian forces, and were ambushed as they attempted to escape, with untold numbers killed.

Much of the political fallout will depend on how big the Debaltseve losses were. So far, the government is saying at least 13 soldiers were killed, 157 wounded, 90 captured and 82 missing.

But the actual figures might be much higher. Also potentially damaging could be the reportedly slapdash, chaotic manner in which the evacuation was carried out, with soldiers escaping on foot after their vehicles were destroyed, and large amounts of armour and ammunition left behind.

Tensions in the ranks

Already there are rumblings of public discontent.

"I have seen this with my own eyes, on the battlefield and in the army headquarters, how military action is planned and executed," Semyon Semenchenko, commander of the volunteer Donbass battalion, told the BBC.

"I can assure you that we lost Debaltseve not because of the Russian military advantage, but because our generals refuse to take responsibility," he said.

Mr Semenchenko has proposed a "parallel" co-ordinating structure for the volunteer battalions fighting in the east. So far 13 battalion leaders have signed up, including Dmytro Yarosh of the nationalist Right Sector.

Mr Semenchenko insists this is not to replace, but to help, the army's general command in "information exchange, planning, logistical assistance and facilitating mobilisation."

Still, his announcement raised concerns. Eight battalion commanders have refused to join the body, calling on Mr Semenchenko to "end his daily populist and PR statements"., external

The detritus of battle litters the landscape around Debaltseve

Setback for Poroshenko

President Poroshenko seems to have a firm grip on power, and many Ukrainians believe he is doing his best in a horrible political and economic situation. Nonetheless, his popularity is slipping.

A recent poll showed, external his approval rating had decreased from 57% to 45%, with 46% saying he was doing a bad job. The "don't knows" were 9%.

Debaltseve has not helped matters at all. And it is possible that the defeat - should the truth be worse than what is being presented at the moment - could significantly damage the Ukrainian president.

Which raises the question: Why did Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel and France's President Francois Hollande push so strongly for a peace deal, if it was already clear during the negotiations that Debaltseve would fall and weaken their ally, Mr Poroshenko?

It is conceivable that Russia's President Vladimir Putin and the insurgent leaders promised to observe the ceasefire the minute it went into effect at midnight on Sunday morning.

If that were the case, then another question arises: Why are European leaders insisting that the Minsk ceasefire deal is not dead, given that the Russians and rebels dissimulated and violated it so blatantly from the outset?

The answer to this may be very simple - Ms Merkel and Mr Hollande have no other option.

President Poroshenko (right) met battle-weary troops in Artemivsk

Limits of EU clout

The massive rebel offensive has revealed the limitations of European leverage. Whatever diplomatic efforts they undertake, these are completely dependent on the goodwill of Mr Putin and the Russian-backed militants.

Some argue that now the militants have achieved their strategic goal of taking Debaltseve, the peace plan can begin in earnest - though so far none of its provisions have been implemented.

But if the insurgents do not want to observe the agreement, there is nothing to stop them. Debaltseve was declared an "exception" - the peace deal did not clarify its status. Tomorrow, Mariupol on the south coast could be called the same, and Western governments would be helpless to prove otherwise.

At the moment, Kiev, Brussels and Washington haven't the necessary carrots to entice the Russians and rebels to come to the table, nor big enough sticks to force them to comply.

Complicating any European plans for a peaceful settlement is the fact that Mr Poroshenko may feel he now needs, post-Debaltseve, to initiate some sort of military campaign to bolster his and Ukraine's position.

"Obviously, it's bad to lose," Mr Putin offered in reaction to the Ukrainians' defeat. "But life is life, and it still goes on."

One wonders if the Russian leader would have been so philosophical if it had been the insurgents who had suffered a rout. And needless to say, many Ukrainians, including Mr Poroshenko himself, may not feel as upbeat, after losing so many of their countrymen.