Is Nato looking the right way?

- Published

The latest ceasefire in eastern Ukraine still looks fragile

It is a truism that the world looks very different depending on where you stand. This thought struck me powerfully just a few days ago when I was in Paris.

With the Ukraine crisis developing and the ceasefire struggling, much of the British and US media foreign coverage focused on the growing strains with Moscow. In contrast French, and for that matter Italian, newspapers were looking in a very different direction.

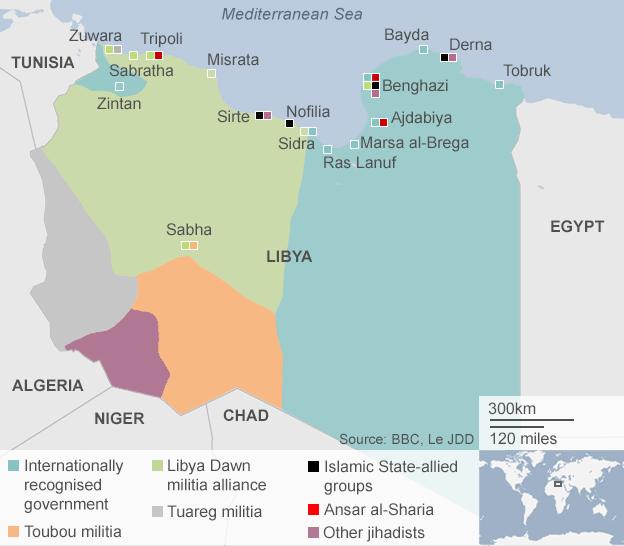

Their concern was to the south; the worsening chaos in Libya and the threat from a massive ungoverned space just a few hundred kilometres off Europe's Mediterranean coast. Worse still is the possibility that parts of Libya could be incorporated into Islamic State's burgeoning caliphate.

Never has the "arc of instability" extending through the Middle East from the Mediterranean seaboard through the Sinai Peninsula and up into Lebanon, Syria and on into Iraq looked more unstable.

Established state structures are collapsing; the heady hopes of the Arab Spring have turned into a nightmare; the only organised political force that has at all benefited from the chaos is the most extreme face of political Islam.

So with Nato largely looking eastwards towards the perceived threat from a resurgent Russia, is the more imminent danger actually creeping up from the south - a tide of instability bringing with it a massive wave of refugees; an unbridled source of arms; and the potential for the infiltration of jihadist extremists on to Europe's shores?

Numbers of refugees crossing the Mediterranean so far this year are well up

Unlike a direct threat to Nato territory from Russia - which the alliance seems to be gearing itself up to deter - what can it actually do about the problems across the Mediterranean?

'Not a job for the alliance'

A week or so ago, Italian Defence Minister Roberta Pinotti spoke of her country's willingness to lead a coalition of states to counter the advance of an Islamic caliphate - Italy, after all, is the former colonial power in Libya and retains significant economic ties with the country.

Other Italian leaders - not least Prime Minister Matteo Renzi - have been more cautious. He noted the other day that "this was not the moment for a military intervention".

The outgoing chief of the defence staff, Adm Luigi Binelli Mantelli - Italy's top serving officer - backed up that view this week, noting that the best tools available for the moment to deal with the Libya crisis were "diplomacy and the UN Security Council".

Libya, though, is of course very much on Nato minds. Developments there are being watched carefully. To the extent that there might be a military dimension to any response it could involve air, sea and even potentially land elements.

Nato reaction forces, for example, could equally be deployed southwards as much as eastwards. But for now the view among senior Nato figures is that this is not a job for them. Libya presents a complex amalgam of humanitarian and security threats for which military means provide no simple answers.

Just consider the humanitarian aspect. Some 300 people died last week off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa and nearly 3,000 had to be rescued last weekend.

Not all the refugee flow is coming from Libya, of course. According to UN refugee agency figures, nearly 220,000 people crossed the Mediterranean last year and the numbers for last month are already 60% up on January last year.

A growing stream risks becoming a torrent and there have been signs that Islamic State leaders are well aware that this refugee flow could be used as a potent weapon to cause disruption in southern Europe.

The situation on the ground in Libya itself is complex, and this makes it hard to really get a grip on the scale of the IS phenomenon in the country.

Just as in Iraq, various armed groups have rallied to the IS banner or sought local advantage by affiliating with it.

The Libyan city of Benghazi is now largely in the hands of Islamist fighters

What is clear is that IS is prospering from the factionalism and chaos created by the division of "government" - to the extent that there is functioning government - between two separate armed coalitions, only one of which is recognised by the international community.

For now it is Nato's southern members who are most alarmed by developments in Libya. But that concern could spread if events there continue on their current trajectory.

Libya matters because it is seen as being so much closer to Europe's shores than the parallel dramas in Iraq and Syria.

How different it was just a few years ago when Nato's air campaign in 2012 heralded the demise of the Gaddafi regime. That was hailed by Britain and France as almost a model intervention. But in retrospect it may have helped to pave the way for the chaos that ensued.

It is always easy to condemn policy decisions in hindsight. But the performance of some of Nato's key players in the run-up to the Libya intervention has drawn criticism. In some ways it is a similar situation to that illustrated by the latest House of Lords report, external, which is scathing in its criticism of the lack of strategic thinking across the European Union in the run-up to the Ukraine crisis.

The events unfolding around Europe's borders are of historic significance and the instability looks set to last for a long time. The response of the West, Nato, the EU - however you want to label it - has been limited, focused on the short term and profoundly political rather than genuinely strategic.

The other day I was sitting with a senior US Nato diplomat talking about the question of arming government forces in Ukraine. He accepted that there were some divisions between advocates of such a policy on Capitol Hill and some of America's key allies - with the Germans in the vanguard of the opposition.

But his key point was that any decision to go ahead with weapons supplies must look at not just their immediate impact but at the second and third-order consequences of such a step.

Naive and frothy

Was this done seriously in London and Paris before the decision to intervene in Libya? Officials and ministers will no doubt say "of course it was". But then wasn't the chaos that has ensued entirely predictable?

These are big questions. They point to the experience, capabilities and expertise of our foreign policymakers - a theme highlighted by the Lords report. Most of the UK experts I speak to on the Russian military, for example, used to work in one way or another for the Ministry of Defence but were dispensed with as a saving after the Cold War.

Where were the experts on the Middle East to advise against the naive and frothy assessments of the Arab Spring that saw it simply as an upsurge of the Twitter generation destined to bring democracy and to overthrow tyrants?

There are fundamental questions too about the way in which policymakers relate to their political masters.

Have they perhaps imbibed the same short-termism and focus on presentation of the wider political class?

In short, where is the "strategic" vision to guide policy through these tumultuous times?