The lessons from Russia's latest killing

- Published

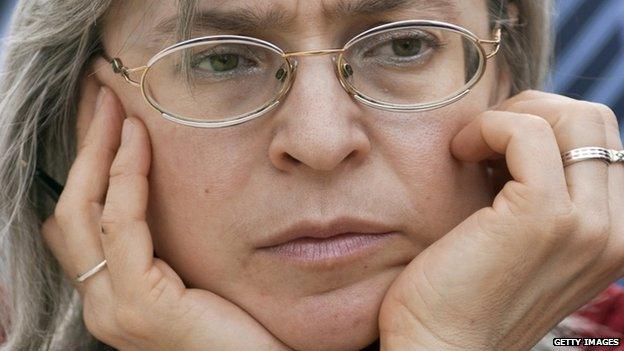

Anna Politkovskaya was murdered in the lift of her block of flats in 2006

Judging by previous political killings in Russia, the mystery of who ordered the shooting of Boris Nemtsov may never be solved. But some lessons from the past may be worth noting.

The murder of a high profile Kremlin critic is nothing new in Putin's Russia.

There was widespread grief when the award-winning journalist Anna Politkovskaya was shot dead, external outside her Moscow home in 2006.

Paul Khlebnikov, the US journalist who edited the Russian edition of Forbes magazine was gunned down, external near his Moscow office in 2004.

And mystery surrounded the suspected poisoning of the Russian MP and corruption investigator Yury Shchekochikin, external in 2003, (three years before the infamous poisoning of another Kremlin opponent, Alexander Litvinenko.)

On their own none of these, nor the many other apparently politically motivated killings over the last 15 years, changed the climate, though they did add to a growing sense of unease about possible dark undercurrents in Russian politics.

Yet assassination is not just a phenomenon of Putin's Russia.

In 1998, there was general dismay when the respected Russian MP and human rights campaigner, Galina Starovoitova, external, was gunned down in St Petersburg.

In 1995, many were shaken at the brazen murder of Vladislav Listyev, at the time the head of one of Russia's biggest television stations.

Galina Starovoitova was gunned down

In fact, the extent of the gangland-style shootings in the chaotic 1990s - targeting journalists, business figures and politicians - was often cited by President Putin as one means of measuring the success of his rule, because he liked to argue that he ended this sort of anarchy and brought peace and prosperity to Russia.

Public killing

What is different about Boris Nemtsov's murder is how public it was.

This was not carried out in a shadowy doorway or foyer. It was not a mystery poisoning. It was in the full glare of street lights, on a busy bridge right in front of the Kremlin, designed to attract attention and therefore to send a political message.

An act of terror in fact, to unsettle society and raise tensions. But in whose interests?

Russia's unexplained deaths:

1995: Television boss Vladislav Listyev shot

1998: Russian MP and human rights campaigner Galina Starovoitova shot

2003: Yury Shchekochikin suspected poisoning

2004: US journalist Paul Khlebnikov shot

2006: Journalist Anna Politkovskaya shot

2006: Dissident Alexander Litvinenko poisoned

On the face of it, this is not good for Mr Putin. Yes, he is rid of an outspoken critic.

But such a flagrant assassination on the doorstep of the Kremlin has grim echoes of the 1990s and undermines Mr Putin's claim that he has restored stability to Russia.

Nor is it really believable that it was the work of Mr Nemtsov's opposition allies, with the aim of smearing President Putin and building support for their protest movement.

Thousands may have turned up for Sunday's march and thousands more for the mourning ceremony on Tuesday.

But surely, longer term, the chilling message of this murder is that if you dare speak out against the Kremlin, you may not be safe from an assassin's bullet?

So could more shadowy forces have taken the law into their own hands, empowered by all the talk in Russia today of "enemies within" and "traitors"? Many analysts are concluding that this is the most likely option.

But there is another scenario doing the rounds. Those close to the Kremlin have cast blame on Russia's foreign enemies.

It is worth noting that this idea was first aired by Mr Putin himself during his 2012 election campaign.

"I know this method and these tactics," Mr Putin said.

"For a decade there have been attempts to use them, especially abroad. This is true, and I know about it.

"They are even looking for a so-called sacrificial lamb, somebody famous. They would off him - excuse me for the expression - and then blame the authorities. People over there are capable of anything."

At the time, it seemed a far-fetched possibility. Now it echoes what Russian television and Russian officials say repeatedly: that Russia is under threat from foreign powers seeking to undermine and destabilise it.

Pretext for repression

Credible fears, if you believe the Kremlin, dangerous scaremongering which could serve as a pretext for repression, if you don't.

So if Boris Nemtsov's murder was more public and political than most, what impact might it have?

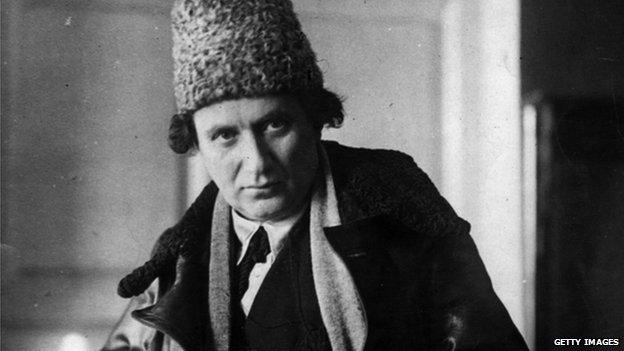

Grigory Zinoviev was executed in 1936 for conspiring to murder Sergei Kirov

Those who are fearful draw a parallel with the murder of Sergei Kirov,, external the head of the Leningrad Communist Party in 1934.

His death paved the way for the so called Great Terror, the purge of Stalin's opponents which led to thousands being killed and imprisoned.

That is one extreme.

Sergei Kirov murder:

Sergei Kirov was the popular head of the Leningrad Communist Party

He was thought to pose a threat to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

On 1 December 1934, Kirov was shot and killed by a gunman at his offices

Stalin was never officially tied to the crime. But he used the murder as a pretext to unleash the Great Terror, which eliminated thousands of political opponents

The other is that there will be no dramatic change, but a slow tilt in one direction or another.

So what should we look for?

Possibly President Putin could use it to reinforce his claim that Russia is under threat and therefore his control over the country needs strengthening.

He has form on this.

After the terrible Beslan tragedy, external when a school was attacked by Chechen and Ingush terrorists in 2004, his immediate instinct was not to call for a security review to find out why the plot had not been spotted or stopped.

Instead, he called on Russians to mobilise against an external enemy who he claimed was seeking to divide and weaken the country.

Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned

And he promptly tightened control over politics by raising the bar for opposition parties to get into parliament and abolishing direct elections of regional governors.

But possibly President Putin will recognise the danger of fuelling public anger against a so-called fifth column of traitors, command his propaganda machine to tone down its rhetoric and allow the opposition more space to express itself.

After all, Sunday's march was allowed to proceed largely without arrests or police harassment.

And Russian state-run TV coverage of Nemtsov's funeral was prominent and respectful, in deference to the victim of a terrible murder.

Let us see. Already there is a growing list of Kremlin critics who have decided that in the current climate, they are safer out of Russia, in self-imposed exile.

- Published13 February 2015

- Published6 November 2014

- Published25 June 2014

- Published6 June 2014