Why has the Nobel Peace Prize chairman been demoted?

- Published

Mr Jagland presents President Obama with the award, which surprised many around the world

For the first time in its more than 100-year history, the committee that awards the Nobel Peace Prize has demoted its chairman.

But what made Thorbjoern Jagland step down?

His six years at the helm have certainly seen some controversies.

Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, less than a year into his presidency.

The European Union was recognised three years later, when the eurozone crisis threatened to rip it apart.

But it was the award given in 2010 to Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo that has prompted speculation about Mr Jagland's removal as chairman.

China was outraged at the decision. It froze top-level diplomatic relations with Norway, imposed visa restrictions and banned salmon imports, a valuable industry for the Scandinavian nation.

So is his demotion a peace offering to China?

Mr Jagland has been replaced by Kaci Kullmann Five, who called him a "good leader"

"It can be interpreted that way," said Asle Sveen, who has written several books on the Nobel Peace Prize. "China viewed him as the main person responsible."

The Nobel Peace Prize office declined to provide a statement, saying that it does not comment on decisions by the committee.

But the new chair, Kaci Kullmann Five, has denied any concession to China. She said she "wholeheartedly" supported the award to Liu Xiaobo.

Shifts in Norwegian politics may be a factor.

The committee is appointed to reflect the make-up of the Norwegian parliament: in the 2013 general elections, the right-wing Conservatives ousted left-wing Labor.

Nobel Peace Prize - famous former winners

Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk (1993, jointly), for their work ending apartheid in South Africa

Mikhail Gorbachev (1990), last leader of the Soviet Union

Lech Walesa (1983), Polish leader of the solidarity movement

Mother Teresa (1979), founder of the Order of the Missionaries of Charity, dedicated to helping the poor

Martin Luther King Jr (1964), US civil rights activist

Mr Sveen is concerned the demotion could mean a more politicised committee, which is supposed to act independently of the Norwegian government.

"The committee could argue that it is quite natural, but it's not natural in the context that it has never happened before.

"Previous leaders have not had political backing yet haven't been removed."

Norwegian journalist Bjorn Ivar Voll agreed that the changes at the Nobel Peace Prize could be down to domestic politics.

With Mr Jagland remaining on the committee, he questioned the gesture's effectiveness: "It's a half measure - getting rid of the man responsible but retaining the rest of the board."

The committee's decision to give the prize to Liu Xiaobo enraged China

And if Norway had hoped the measure would shift China's position, those hopes have already been dashed.

A Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman, Hua Chunying, would not be drawn on whether the two countries had discussed the issue, but said their relations had "not changed".

Rod Wye, a China expert at the Chatham House think tank in London, said he doubted Mr Jagland's removal would make any difference.

"China is sending a message - don't mess about with what we feel is our vital interest because you will hurt yourselves more than us."

So what then, could Norway do to reconcile with China? "Goodness knows," he replied.

Norway has made conciliatory gestures before, such as when the government refused to meet the Dalai Lama during a visit last year, whom Beijing considers a pariah.

But it is also well positioned to weather China's ire, with exports there making up less than 2% of the Norwegian economy. Trade in most industries has continued between the two nations despite the diplomatic freeze.

Dr Peter van den Dungen, an expert in the award at the University of Bradford's Department of Peace Studies, called the row a "storm in a teacup".

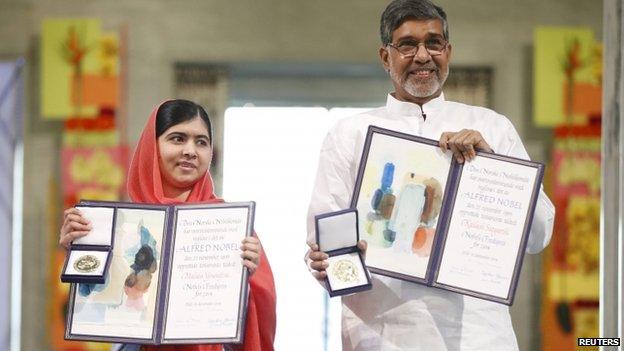

Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi were the most recent winners of the prize

He said it risked overshadowing more important questions about the Nobel Peace Prize itself, pointing to a campaign to reform the award, external.

"The prize is effectively being given for 'good work' - in a sense anything like this can be linked to peace.

"It has lost sight of the original aim of the prize, as intended by Alfred Nobel - to promote disarmament and the peace movement."

Meanwhile, the awards process continues. This year the committee considered a near-record 276 nominations, including Pope Francis and NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden.

And it is worth pointing out that controversial winners are not a modern phenomenon.

In 1906, the award went to then US-president Theodore Roosevelt, leading to accusations that newly independent Norway was pandering to a powerful figure, just as it would with President Obama more than a century later.

- Published10 October 2014

- Published10 December 2010