Could Europe lose Greece to Russia?

- Published

Greece may need new loans to avoid bankruptcy when its bailout extension expires at the end of June

Deepening ties between Greece's new government and Russia have set off alarm bells across Europe, as the leaders in Athens wrangle with international creditors over reforms needed to avoid bankruptcy.

While Greece may be eyeing Moscow as a bargaining chip, some fear it is inexorably moving away from the West, towards a more benevolent ally, a potential investor and a creditor.

Europe is not pleased. Should it also be worried?

Worst kept secret

A drove of Greek cabinet members will be heading to Moscow.

Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras will be hosted by Russian President Vladimir Putin in May, accompanied by coalition partner Panos Kammenos, defence minister and leader of the populist right-wing Independent Greeks party.

The timing has not escaped analysts.

Greece's bailout extension expires at the end of June and the worst kept secret in Brussels is that Athens will need new loans to stay afloat.

Open arms: Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias (L) had a warm welcome in Moscow in February

Officially, Greece is not searching for alternative sources of funding.

But a loan from Russia, or perhaps China, could seem a more favourable alternative - or at least supplement - to any new eurozone bailout with all its unpopular measures and reforms attached.

Greece could look forward to cheaper gas for struggling households, increased Russian investment and tourism to provide a much needed economic boost.

Moscow, in return, would be rewarded with a friendly ally with veto power inside the EU at a time of heightened tensions over the Ukraine crisis.

'Russian card'

The new government's intention to forge closer ties with Moscow became evident as soon as the leftist Syriza party won the 25 January election.

Within 24 hours, the first official to visit the newly-elected prime minister was the Russian ambassador, whereas it took German Chancellor Angela Merkel two days to congratulate him with a rather frosty telegram.

On becoming foreign minister, Nikos Kotzias questioned the rationale and effectiveness of EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine and, from day one, the defence minister advocated stronger relations with Moscow.

Like most members of the Syriza cadre, Mr Tsipras and Mr Kotzias descend politically from the pro-Russian Greek Communist Party.

Mr Kammenos, in common with other hard-right European politicians, also has longstanding ties to Russia.

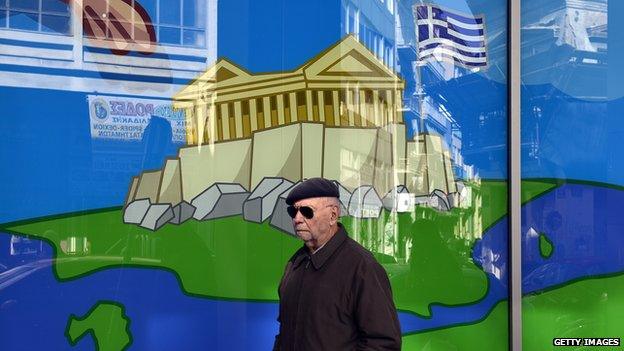

The Greek prime minister, whose party's roots stem from the Communist party, visits Moscow in May

"My feeling is that the Greek government is playing the 'Russian card' in order to improve its bargaining position in the current negotiations," says Manos Karagiannis, a Greece-born specialist on Russian foreign policy at King's College, London.

"But it will be very difficult for Athens to distance itself from the EU and Nato."

It may be premature to say the new government is breaking with the dictum of conservative statesman Constantinos Karamanlis, who declared in 1976 that "Greece belongs to the West".

But this main pillar of Greek foreign policy has been shaken by a deep disgruntlement caused by a financial crisis raging for a sixth year, which has cost Greece a quarter of its GDP, one million jobs and, for many Greeks, the dignity of a proud nation.

And there are some who do not view the new approach as a fleeting convergence of interests.

Especially since a pro-Russian policy plays well with the Greek public.

'Turn to Moscow'

Samuel Huntington's controversial thesis on "the clash of civilisations," which places Greece squarely in the Russian-led Orthodox axis, is rejected by many scholars, but widely accepted by Greeks.

A global survey, external by the Pew Research Center from September 2013 found that 63% of Greeks held favourable views of Russia.

Only 23% of Greeks had a positive view of the EU last autumn, in the latest Eurobarometer survey, external.

Greece's historical ties to Russia are not just religious and go back to the birth of the modern state

"It is clear that Germany wants to impoverish our people," says Kostas Iliadis, a supermarket worker in Thessaloniki. "Our response should be to turn to Moscow, even if this means that they kick us out of the EU."

This positive image of Russia has deep roots in history:

When Greece was still part of the Ottoman Empire, Greeks often looked to fellow Orthodox Russians for help

Greece's War of Independence was initiated in 1821 by a secret group formed in Odessa known as Society of Friends (Filiki Eteria)

Ioannis Kapodistrias, a Greek foreign minister of the Russian Empire, was elected first governor of the fledgling independent Greece in 1827

The "Russian party" was a dominant political force in the new state

More recently, the 2004-09 conservative government of Costas Karamanlis, nephew of the veteran pro-Western statesman, pursued a "diplomacy of the pipelines", envisaging Greece as a gateway for Russian oil and gas to Europe.

It was a policy that enraged Greece's Western allies.

Mr Karamanlis was rejected by voters a year after signing a gas deal with President Putin

After he lost elections in 2009, it emerged that Russia's FSB security agency had warned its Greek counterpart, EYP, of a 2008 plot to assassinate Mr Karamanlis to halt his pro-Moscow energy alliance.

'No crime or sin'

All this makes Europe, and especially Germany, uneasy.

"Who is more dangerous for us? The Greek or the Russian?" pondered, external mass-circulation German tabloid Bild.

Greek foreign ministry spokesman Constantinos Koutras says there is no need for alarm.

"Pursuing a multi-dimensional foreign policy is not forbidden, and it is neither a crime nor a sin," he told the BBC.

Cyprus President Nicos Anastasiades signed a military cooperation deal with Mr Putin last month

Critics say it would be unwise for Greece to place too many hopes on Russia anyway, arguing that Russia has a long track record of frustrating Greek aspirations.

After all, Moscow did nothing to help Cyprus, also an Orthodox country, when its tiny economy was on the point of collapse in 2013.

President Putin did offer Cyprus more investment and better repayment terms for a €2.5bn (£1.7bn; $2.6bn) loan last month, but only after President Nicos Anastasiades agreed to give Russian military ships access to Cypriot ports.

For Prof Karagiannis, what matters is that Greece is fully integrated into the West, but he warns against underestimating the risks of a Greek exit from the euro.

"A Grexit could certainly fuel anti-EU sentiments among the Greek population. And an isolated and weak Greece could jeopardise the stability of the entire region," he says.

A weakened country, cast out of the eurozone and possibly the EU, would then be far more open to closer ties with Russia.