Alps plane crash: What happened?

- Published

The co-pilot of a Germanwings flight that crashed into the French Alps may have practised a rapid descent only hours before he sent the plane plunging into the mountainside "intentionally", according to French investigators.

Evidence from the Flight Data Recorder (FDR) showed Andreas Lubitz had repeatedly changed the setting of the altitude controls during the plane's flight from Duesseldorf to Barcelona earlier, but as the plane was on autopilot its planned descent was not affected.

Later the same day Lubitz was alone in the cockpit during the flight from Barcelona back to Duesseldorf when he initiated the plane's dive. He refused to allow the captain back through the cockpit door or respond to air traffic control. Speculation over the reasons for his actions has centred around the co-pilot's mental wellbeing.

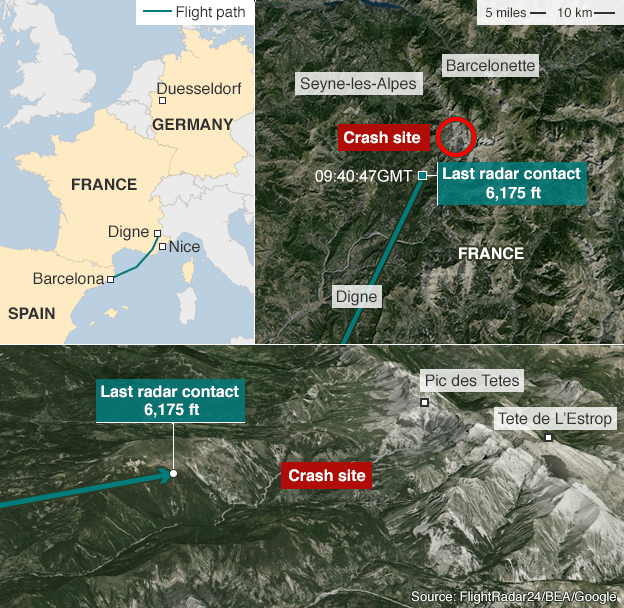

The German A320 Airbus flight 4U 9525 from Barcelona to Duesseldorf came down in a remote mountain valley in France on Tuesday 24 March, killing all 150 people on board.

Debris in Alps crash zone

Debris from the crash can be seen spread across the mountainside in the remote region of the French Alps

What happened?

Richard Westcott on what we know from the cockpit voice recorder

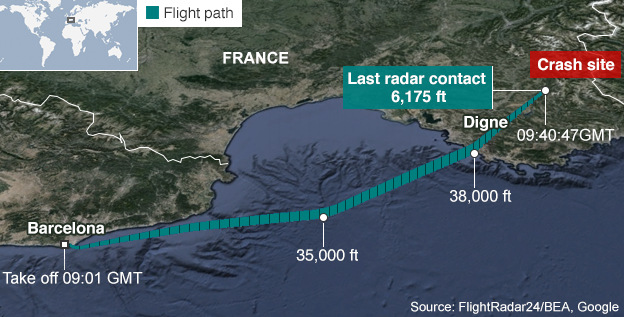

The plane took off from Barcelona at 09:01 GMT on 24 March. Reports from Flightradar24, external, which tracks air traffic around the world, said the Airbus climbed to 38,000ft within the next half hour.

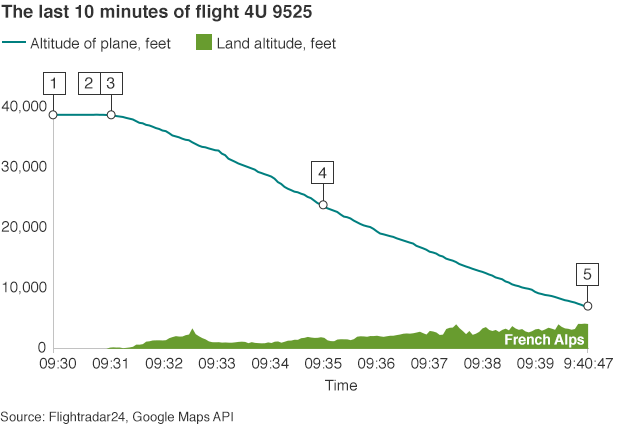

At 09:30 the plane made its final contact with air traffic control - a routine message for permission to continue on its route.

One minute later it began to descend. The descent lasted nearly 10 minutes before last radar contact with the Airbus at 09.40:47.

The Airbus crashed in a remote, snow-covered mountainous region, external - some parts reaching about 1,500m (4,900ft) high - that is inaccessible by road.

On 26 March, French investigators said information from the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) - found at the crash zone revealed that co-pilot Andreas Lubitz had taken over the controls of the plane and sent it into a dive intentionally., external

The captain, named by German media as Patrick Sonderheimer, had left to go to the toilet, leaving Mr Lubitz in sole control. At this point, the co-pilot activated the plane's descent.

It was Mr Lubitz's "intention to destroy this plane," Marseille prosecutor Brice Robin said.

The cockpit voice recorder, discovered at the crash site, has given investigators details of the last 30 minutes of the flight. , external

For the first 20 minutes, the two pilots talked normally, prosecutors said, then the captain is heard asking the co-pilot to take over. The sound of a chair being pushed back can be heard followed by a door being closed.

Then, during the final minutes of the flight's descent, pounding can be heard on the door and muffled voices as the captain tried desperately to get back into the cockpit. Alarms also sounded, warning the pilots to "pull up".

The Marseille air traffic control centre and the French Air Defence system both attempted to contact the flight crew several times.

While the co-pilot did not say a word after the commanding pilot left, his breathing could be detected, indicating he was still alive at the time of the impact, Mr Robin said.

At 09:41:06 the CVR ceased recording when the plane hit the ground.

1. 09:30 - Plane makes final contact with air traffic control. Captain believed to have left the cockpit at this stage.

2. 9:30:55 - Autopilot is manually changed from 38,000ft to 100ft, according to data analysis by Flightradar24, external.

3. 9:31 - Aircraft begins its descent, with only the co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz, in the cockpit.

4. 09:35 - Air traffic controllers try to contact the pilots, but receive no response.

5. 09:40:47 - The last radar position of the plane is registered at 6,175ft, just 2,000ft above the mountains of the French Alps.

There has been speculation that the co-pilot's actions were a result of mental health problems. Investigators found anti-depressants at his house along with evidence of treatment by various doctors, including a torn-up sick note for the day he flew the plane.

There have also been a number of newspaper reports he had faced problems with his eyesight, external - possibly a detached retina - which could have affected his ability to carry on working as a pilot.

The interim report by French accident investigation agency BEA confirmed Lubitz had been treated for depression in April 2009 and subsequently his pilot's licence was issued on condition he undertook certain regular medical checks.

'Black boxes'

The plane's CVR - one of its two "black boxes" - was retrieved from the crash zone, although in battered condition.

The second box, recording technical data, was recovered a few days later. It was also severely damaged - but did reveal information about the previous flight from Duesseldorf to Barcelona.

An aircraft's flight recorders are often the key to establishing what caused a plane to crash. Each plane carries two recorders: the CVR and the flight data recorder (FDR). Although they are popularly known as black box recorders, they are, in fact, orange to aid in recovery.

The CVR, as the name suggests, records the voices of the pilots and other sounds from the cockpit.

It retains two hours of recording - on longer flights, the latest data is recorded over the oldest. On some older models, magnetic tape is still used for the recording, but newer models use memory chips.

The FDR records technical flight data, including at least five basic sets of information: pressure altitude, airspeed, heading, acceleration and microphone keying (the time radio transmissions were made by the crew).

The FDR retains the last 25 hours of aircraft operations and, like the CVR, data is recorded on an endless loop.

Both recorders are designed to withstand a massive impact and a fire reaching temperatures up to 1,100C for 60 minutes.

The interim report by BEA, external, released on 6 May 2015, published a chart using data from the FDR, showing how Lubitz altered the altitude setting to the minimum 100ft several times, when the captain left the cabin. But each time he changed it back to the correct level after just a few seconds.

Because the plane was on autopilot on a planned descent to Barcelona, its actual course was not altered.

"I can't speculate on what was happening inside his head - all I can say is that he changed this button to the minimum setting of 100ft and he did it several times," BEA director Remy Jouty told Reuters news agency.

Debris field

Debris from the aircraft was spread across an area of about four hectares (10 acres), about 1,550m up the mountainside in a sloping rocky ravine. The largest pieces of wreckage were 3-4m long.

Parts of the plane's wings and fuselage were found towards the bottom of the ravine, where tree trunks had been uprooted and the ground was churned up.

The aircraft

The plane is one of the oldest A320s in operation. It entered service for the German airline in 1991.

It had passed a routine maintenance check only the day before the flight.

Co-pilot Andreas Lubitz, 27, joined Germanwings in September 2013, directly after training, and had flown 630 hours.

Lufthansa said the captain had more than 6,000 hours of flying experience and had been with Germanwings since May 2014, having flown previously for Lufthansa and Condor.

Lufthansa said its cockpit protocols are in line with rules established by the German aviation safety authority. These stipulate that when there are two crew, one can leave the cockpit but only for the absolute minimum time.

EASA - the European Aviation Safety Agency - has since issued new guidelines requiring two authorised staff to remain in the cockpit at all times.

Who was on on board?

There were 144 passengers on board the plane, four cabin crew and two more crew in the cockpit.

Germanwings officials said victims included 72 German nationals, among them 16 school students. The Spanish authorities say there were 51 Spaniards.

Other victims were from Australia, Argentina, Britain, Iran, Venezuela, the US, the Netherlands, Colombia, Mexico, Japan, Denmark and Israel.

This map from Flightradar24 shows the plane's route

- Published26 March 2015

- Published26 March 2015

- Published24 March 2015

- Published27 March 2015

- Published26 March 2015

- Published21 March 2022