Germanwings: Why visit the site of a relative's death?

- Published

A bus transporting the families of the Germanwings Airbus A320 victims arriving in Seyne-les-Alpes

More than 100 relatives and friends of victims of the Germanwings 4U 9525 crash have arrived in the small village of Seyne-les-Alpes, near the site of the disaster.

The relatives will reportedly travel as a group to a point near the disaster in the mountainous terrain. Part of the crash site will remain closed off to everyone except the investigators and emergency workers tasked with clearing the area up.

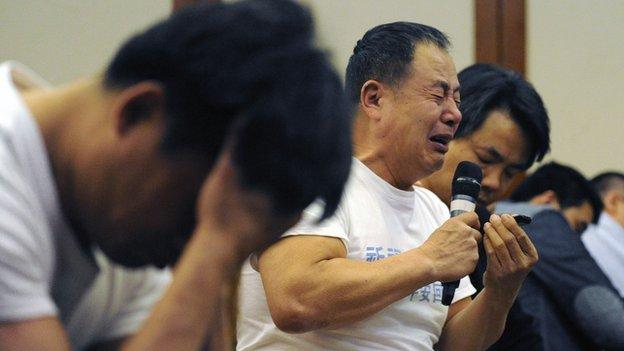

Besides the bewilderment, shock and grief, this group must have a long list of unanswered questions, especially following the announcement from officials that the plane was intentionally brought down by the co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz.

Who was he? Why did he do it? How was it allowed to happen?

Getting answers is probably more important than being close to the crash site, says Roderick Orner, a clinical psychologist who specialises in the immediate aftermath of trauma.

"Having good communication is not going to take their distress away, but it makes it less of a burden to carry. The mind is all cluttered with these kind of questions but also what happens in the aftermath is people get into these hyper-aroused states, they are agitated. And you saw that after the Malaysia MH370 incident.

"Those people were left in a suspended, agitated state, and then they just lost it. And in this situation people don't sleep and it just gets worse and worse."

Relatives of those missing aboard MH370 have been through an agony of waiting and not knowing

The best thing the relatives can do, Prof Orner says, is be in contact with other people. The relatives in the Alps are in a group, which should help, but this morning's news that their family members were seemingly killed on purpose will make recovery difficult. "Evidence from research tells us that trauma inflicted by other humans with intent is more difficult to come to terms with than, for example, natural disasters."

Sabine Rau, a psychologist working for the city of Dusseldorf to support victims of the crash, told the BBC on Wednesday that she was focused on getting "the maximum amount of information" to relatives to give them certainty.

"People know a plane has crashed, but they don't know what that means for them," Ms Rau said. "What does that mean for my family, for my child, my parents - that is the paramount question. What does it mean to me?"

She described the opportunity for relatives to visit the crash site as "a wonderful option in a terrible, horrible situation", but she said that not everyone will want to take the offer up.

Lufthansa, the owner of Germanwings, is paying for the relatives' trip and has said it will adapt to their needs. Those that have made the trip to Seyne-les-Alpes can either remain there or be flown back to Spain tonight.

Taking relatives of victims to the scene of a disaster can be an effective form of treatment for shock and grief.

Lars Weiseth, a professor at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies, has organised trips for families to the site of an avalanche, the Asian Tsunami and the scene of a plane crash (the Linate Airport disaster in Milan in 2001).

He was also the lead psychiatric advisor following the 2011 massacre in Utoeya, Norway, where Anders Behring Breivik killed 69 people and injured 33 others. He arranged for police officers to accompany family members of 55 of Breivik's victims to the sites of their relatives' deaths. Examining the effect of this trip on those relatives, he found a more marked drop in post-traumatic stress responses than in relatives who had chosen to stay at home.

The profound urge to undertake such trips is first and foremost about gaining an understanding of what went on before someone's death, Prof Weiseth says, but there are other motivations too.

Members of the public pay their respects near Utoya island following the attacks by Anders Behring Breivik

"The second factor is the nearness to the dead person," he says. "The site of death is almost like the grave and gives you a very strong sense of physical closeness to the deceased.

"A third factor is the almost duty-like sense you have. A sudden, violent death means there is no time to bid farewell.

"When I talk to people who have done this I really think it's almost a religious sense of duty. You have to overcome a resistance and a fear - it's really an effort - and I feel you do this for the missing family member.

"Then there is also finally an anti-phobic thing, you overcome your fear by doing something with others. There is this cohesion, this sense of mutuality, and on the site you can carry out some symbolic rituals."

Even if relatives of the Germanwings plane disaster choose to remain in Seyne-les-Alpes and not inspect any debris, Prof Weiseth says it may help them. They will have a sense of doing something.

Emergency workers holding up flags representing the nations of the victims of the Germanwings crash

Guillaume Denoix de Saint Marc visited the crash site of his father's plane 17 years after the event. He had been on board UTA flight 772, which was blown up above the Sahara Desert in 1989.

It took years of negotiations to arrange the visit, but when Mr Denoix de Saint Marc, his wife and two other victims' relatives finally saw the wreckage in March 2007, he remembers the group being stunned into silence.

They walked about the debris, not conscious of the hot sun or their thirst. Finally Mr Denoix de Saint Marc was overcome by a sense of rage at the murder of his father. He went on to oversee the construction of a memorial at the site.

"It brings reality to the thing," he says of the trip. "[To begin with] we just had information that the plane was cancelled on the boards but there was no physical link with the plane."

The physicality of the debris was, for him, a vital aspect of his trip to the disaster site. He salvaged a UTA security belt which he still carries with him.

Denoix de Saint Marc was staggered by the sight of the wreckage that still lies in the desert

Relatives rarely need to travel to see debris from air crashes or other disasters - they are visible in newspapers, on the internet and on TV. That can be part of the problem, says Mr Denoix de Saint Marc. The day after his father's plane crashed, he was sitting in a burger restaurant watching a man eating a meal while reading a news story about the crash. "And he was eating a burger and there was ketchup falling on the pictures," he says. "For me it was completely insane. I had to leave."

In the long term it will be important for the families of the Germanwings victims to organise themselves into a cohesive group, he says. Not only will this help them support one another, but it will allow them to take the lead on future discussions, for example about a suitable memorial.

But right now, the authorities have a duty to give them as much information as they can - before everyone else.

"It's our story. As victims, it's our story. Psychologically it's very important but also from a moral point of view.

"It's our event, and we should be treated in a way that we have access to more information. But in fact, it's often the opposite because journalists have more information than the victims themselves. That is shocking."

It's important that relatives get information before the public, says Mr Denoix de Saint Marc