Russians reel from economic crisis

- Published

Sanctions are hitting many people hard

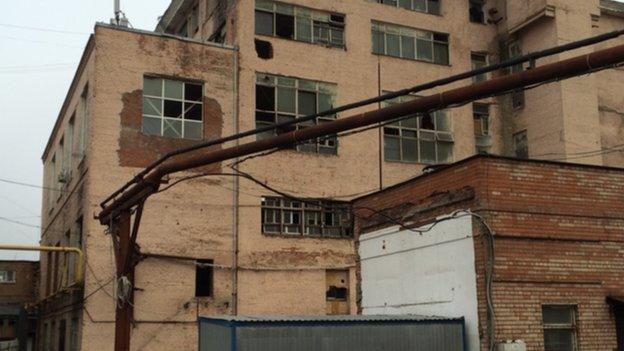

The weed-filled belt of abandoned industrial plants in south-east Moscow looks like a war zone.

In fact, this is indeed where Moscow film-makers come when they need to film a fire fight - it is the perfect backdrop: huge derelict factories with collapsing walls, gaping holes instead of windows and rusty corrugated fencing to keep the drunks out.

In among the ruins there are a few small warehouses and offices.

From one of them, workmen in overalls are clearing out stock and loading crates into a van.

"We've cleared the Chinese stock. Almost 70% of the business has gone.

"We had to fire 15 people. I had to let one lady go who'd worked here for 12 years. You can't imagine how hard it was."

It's not just Finikov whose business is in trouble.

Shrinking economy

Drive down any shopping street in Moscow and you'll see the For Rent signs.

Dmitry Finikov has had to lay staff off

Some enterprises have announced they are cutting back to a three-day week.

In places there have even been workers' strikes.

"It's the problem of the whole economy," says Finikov. "It's shrinking. The retail sales, the wholesale…

"I have a friend who has a business selling fish aquariums. Last year, he was selling four a week. Since the start of this year he's only had two or three customers."

The Russian government is also slashing spending, external.

"Basically everything except military spending is cut by 10%, every budget item… in government agencies, in universities, everything," says Konstantin Sonin, professor of economics at the prestigious Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

"Almost everything related to education and healthcare in Russia is state-controlled or owned, so the staff are state employees. All of them are finding their salaries are being cut."

And the main reason, says prof Sonin, is the global drop in oil prices, which caused the rouble to plummet (though it has rallied somewhat since) and squeezed consumer spending.

Sanctions impact

Western sanctions, external also played a role, in cutting access to credit, discouraging foreign investment and undermining business confidence at home too .

But Sonin says the sanctions also helped mask the fact that the Russian economy was not growing even before the crisis over Ukraine. So in fact, sanctions have given the Kremlin an alibi.

Maxim Chebanov has been doing well

Not everyone is complaining. Some producers have found a way to turn the crisis to their advantage.

On a small dairy farm some 30 miles (50km) from Moscow, 15 cows munch contentedly on hay in their gleaming new barn.

Maxim Chebanov has just moved premises to make room for expansion.

A former manager in a brewery, he switched to farming a couple of years ago to provide high-quality milk and cheese for his young family, selling the rest at farmers' markets.

Then the crisis started and demand escalated.

He has increased his herd five fold in just 18 months due to Kremlin "counter sanctions" which blocked the import of European dairy products and other fresh food.

Chebanov is a perfect example of what President Putin calls "import substitution". He even offers his buyers an "anti-sanctions" discount on his website.

"Sanctions have invigorated people to respond in a more patriotic way," he says. "The longer they last, the better."

But while a handful of dairy farmers may have profited, the main impact of the Russian government's counter sanctions has been negative: a drastic rise in food prices, hitting poorer parts of the population above all.

The cost of medicines also has shot up. The official inflation rate in March was nearly 17%, external.

Provinces suffering

In Moscow, many shoppers said they were coping: either their income was big enough, or they were getting help from relatives. But in the provinces there is much more angst.

One woman in Oryol, a small town south of Moscow, said: "Many people went from here to Moscow in search of work when the old Soviet factories went bankrupt.

"Now those jobs in Moscow are folding and they are coming home. But there are no spare jobs here and prices keep going up. How are they supposed to live?"

She added that she knew many people who had stopped buying meat- too expensive for those with a family to feed.

Russia inflation rate:

March 2015: 16.9%

February 2015: 16.7%

January 2015: 15.0%

December 2014: 11.4%

November 2014: 9.1%

October 2014: 8.3%

Year-on-year figure

But the downturn does not necessarily translate into pressure on the Russian government from its own consumers.

Many people seem to blame the West for all Russia's economic woes.

Maxim Chebanov has expanded his farming operation to cater for increased demand

"It's sanctions that are behind it all," said a shopper outside one Moscow supermarket. "After all, you are the enemy."

And many Russian political analysts conclude that Western sanctions have, in fact, been counter-productive.

"Sanctions may have hurt the Russian economy," says Evgeny Minchenko, an independent political consultant who names the Kremlin among his clients.

"But politically they unite people against the West. Recent polls show the highest level of anti-Western feeling in recent history. It won't be easy to reverse."

At the Higher Economics School - an elite university set up in part to help formulate Russian economic policy - economists say that they are being ignored by a Kremlin inner circle which focuses on imagined enemies rather than economic realities.

Evgeny Minchenko warns that sanctions could be counter-productive

"I cannot imagine a sane economist could be happy with what is going on," says prof Sonin.

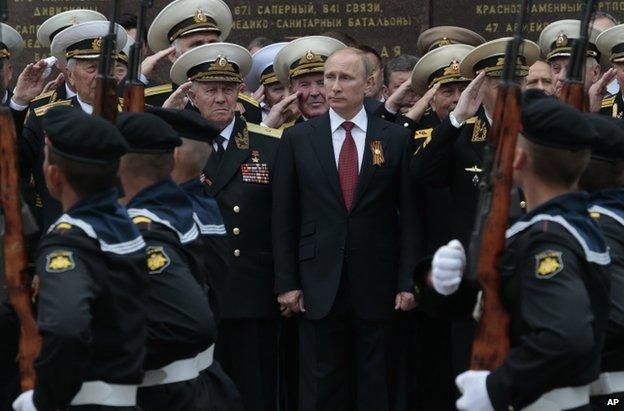

"Economic decision-making is being done by those who work in the military and the security services.

"They invest a lot in military production, because at the top they feel that Nato is close to the walls of the Kremlin and Russia is under siege.

"I think they live in a pretty strange world. They live in an information bubble with their own monsters and nightmares - and the economy is not a major concern."

Struggling for ideas

Kremlin consultant Evgeny Minchenko takes a different view.

He thinks the Kremlin is concerned about the economic downturn, but simply cannot find effective ways to counter it.

His reading is that the attempt to "pivot" to Asia has not yet compensated for the loss of Western business and credit lines; there is only a 20% chance of EU sanctions being lifted in the short-term and repairing relations with the West in the current climate looks unlikely.

Oil prices have been hit

So instead, the Kremlin is focusing on import substitution and other measures to try to make the internal market work better - by cracking down on corruption, and giving tax breaks to small and medium-sized enterprises.

Whether it will work is another matter. Reports on a recent Cabinet meeting suggest President Putin was agitated and frustrated at the lack of young Russians willing to risk opening new businesses.

In theory, Dmitry Finikov is doing exactly what President Putin wants.

He has switched from importing to producing his own lower-quality, Russian-made guns and ammunition.

But it is only out of necessity, not choice.

He explains why small businessmen like him remain pessimistic.

"I used to plan for five years. Now I can only plan for two or three weeks. The Russian economy has been so globalised over the last 20 years, that it cannot survive like this.

"Sooner or later the oil price will go down again, then the rouble will drop again.

"For the moment we are eating into our reserves. But when they are used up, then the economy will drop immediately like it was in 1992.

"You remember: hyperinflation, people losing their jobs and not getting paid for six months or a year, and everyone going out to the suburbs to plant potatoes to feed themselves from the ground."

Gloomy prognosis

The prognosis of prof Sonin is less dramatic but still gloomy.

He compares Russia's likely future to that of many Latin American countries in the second half of the 20th Century: a slight contraction, or growth so slow that it amounts to stagnation, lasting for 10 or even 20 years; and exit from the crisis only possible when the Russian government stops sacrificing the economy to foreign policy goals.

"I do not foresee the lifting of sanctions under the current regime. I think it will be the next government, maybe in 20 years, which will negotiate a solution."

The Kremlin has cut back on spending

Meanwhile, farmer Maxim Chebanov has "Napoleonic" plans- to expand to more than a hundred cows and open a mini-dairy and farm shop.

He thinks the crisis will blow over.

'We Russians have survived crises worse than this. And anyway it's all temporary.

"Sooner or later we'll have money again and foreign investment will return.

"And meantime while sanctions continue, the stronger we will become."

Hear Bridget on the Today programme here.