MH17 crash: My revealing fragments from east Ukraine

- Published

Firefighters put out flames in the main fuselage of flight MH17

When a journalist investigates a crime scene something is wrong. It is not his job. We leave the search for evidence in the hands of the police for a good reason.

But on 17 July 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 exploded over eastern Ukraine and the remains of 298 passengers and crew fell in a warzone with frontlines instead of police lines.

I visited the site several times and, after months of seeing evidence lying at the scene undisturbed, I decided to take some small fragments with me. At least three of them were later linked to a surface-to-air missile by forensic analysis and experts.

360 degree view of fragment linked by analysts to warhead used by Buk missile launcher

Men with guns

The victims came from several countries; 196 were Dutch citizens and my country was in shock.

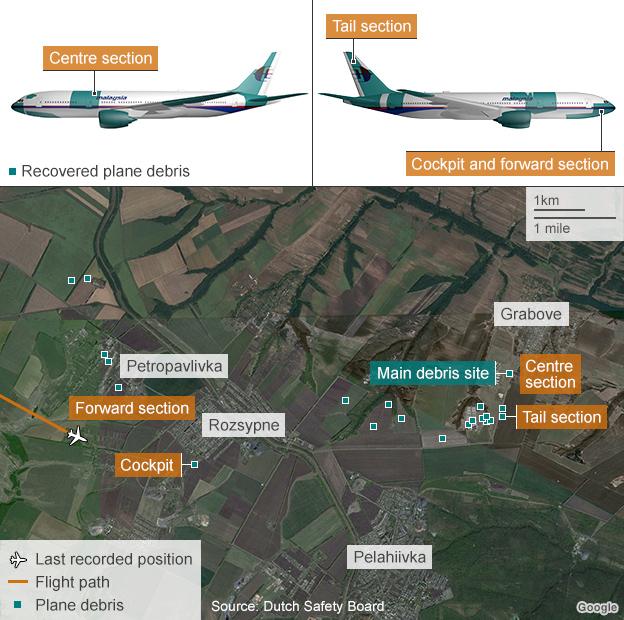

The wreckage of MH17 was spread over more than 35 sq km (13.5 sq miles) and, when I first arrived, flags had already been put in place locating where the body parts were.

There was no order, just men with guns. But nobody stopped us entering and filming what was dubbed "the biggest crime scene in the world".

Everywhere lay desolate parts. It was a scene of war; death; hell.

I took pictures of serial numbers, holes and craters in an attempt to understand the magnitude of it all.

Russian-backed separatists had been fighting the Ukrainian army for control of the MH17-zone and the entrance to the area was obstructed by roadblocks manned by armed rebels.

Part of the front of the plane landed in the main street of Petropavlivka

Investigators from the Netherlands arrived four days later.

By the time of their arrival, Ukrainian firemen had retrieved most of the bodies and body parts from the burning sun, put them in plastic bags and on to a waiting train with refrigerated carriages.

Soon the Dutch investigators were pulled out. Dutch authorities considered the warzone too dangerous for collecting evidence.

Nevertheless the Netherlands was asked to take over the investigation from Ukraine.

Initially the Dutch saw it as a logical and necessary step.

When lines of coffins were flown back and driven by hearse to an army barracks, our small country was in tears.

It felt as if everyone knew a passenger on board MH17.

The Dutch expected nothing less than swift conclusions from their investigators. But the investigators' hands were tied by commitments to Ukraine - even though its army had not been ruled out as a suspect - and by a formal refusal to negotiate with separatists.

A preliminary Dutch report suggested the plane was downed by a large number of high-velocity objects

The delay in collecting the wreckage and reports of body parts still at the scene left a population in mourning increasingly angry and frustrated.

In September 2014 a preliminary report, external indicated MH17 was brought down by a great number of objects piercing the plane with high velocity; there was no evidence of human or technical failure.

It was criticised as too little, too late.

Personally, I saw the report as a clue that many of these objects might still be in the wreckage.

But three months after the crash, still nobody had collected possible evidence.

No investigators. No police lines.

Jeroen Akkermans with some of the fragments from the crash scene in eastern Ukraine

Early in November, on my third visit to the MH17 zone, I took the decision to search for fragments that could not belong to a Boeing or the cargo. I picked up around 20 "suspect" small pieces.

My main suspect was a fragment that looked to me like cluster ammunition: rusty, heavy metal with sharp edges.

I recognised this kind of ammunition from other warzones.

A couple of days after I had left the area, Dutch investigators finally started transporting the first parts of wreckage to the Netherlands.

Getting my fragments out of the country was one thing, getting it analysed was another.

Parts of the plane were found 8km (5 miles) from the main debris site

Forensic back-up

The theory about the downing of MH17 is divided into two camps.

One side is convinced a Ukrainian SU-25 fighter jet shot MH17 down.

The opposing side believes it must have been a Russian surface-to-air missile launched from separatist-held territory.

I spoke to many experts in different countries on possible air-to-air and surface-to-air weaponry and showed them the fragments.

All ruled out air-to-air ammunition. Instead, they were convinced at least three of the pieces I had taken had the markings of a surface-to-air missile. Fired from a Russian Buk missile launcher, perhaps?

Forensic back-up is both essential and expensive.

I was allowed to witness forensic analysis of a piece where the time-consuming peeling of the coating revealed the Cyrillic letter Ц.

Extensive forensic analysis was required to remove the coating from one fragment

Eventually the Russian letter Ц and number 2 became clear

'Pure mathematics'

The rusty fragment - my main suspect - indeed turned out to consist of the heavy metal you would expect for this kind of ammunition, with damage typical of a fragment that had pierced another metal-object with high velocity.

Forensic analysis and experts from British defence analysts IHS Jane's linked the damaged, hour glass-shaped fragment to a 9N314 warhead, which arms at least one type of the Buk system's missiles.

German missile expert Robert Schmucker went through all the data.

"Looking at the damage, the velocity, the height and the fragments, it all adds up to a Buk missile, to me it is pure mathematics," he told me.

After four months of investigation, for the first time we were able to present the public with physical evidence of a Buk.

Far bigger steps to the truth about MH17 still need to be taken. Who is responsible and will they be brought to justice? Quite frankly, I am not optimistic.

But was I entitled to do what I did?

Since my work was broadcast, there has been a public debate in the Netherlands about whether or not a journalist can take evidence from a crime scene.

Some have called me a thief obstructing the rule of law.

I see it instead as my journalistic obligation.

The search for truth is my job. Many agreed.

Unexpected backing came from Dutch Vice Prime Minister Lodewijk Asscher, who told a news conference: "RTL News and Jeroen Akkermans are free to pursue their own investigation."

I have since handed the fragments over to the Dutch authorities. It will be part of their investigation.

298 victims from 10 countries

Netherlands: 196

Malaysia: 42

Australia: 27

Indonesia: 11

UK: 10

Belgium: 4

Germany: 3

Philippines: 3

Canada: 1

New Zealand: 1

Jeroen Akkermans, external is a correspondent for Dutch RTL News. His extensive collection of photographs covering the MH17 disaster can be found on Flickr, external.

- Published10 November 2014

- Published8 September 2014

- Published30 March 2015