The problem with insulting Turkey's President Erdogan

- Published

With US President Barack Obama, they focus on his ears. For UK Prime Minister David Cameron, it's his cheeks; French President Francois Hollande, his stature. And for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the cartoonists go for the downturned mouth, a jowly look that Penguen, arguably Turkey's most famous cartoon magazine, loves to play on.

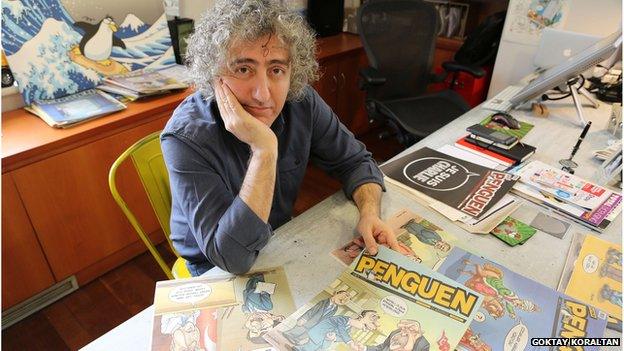

"He provides us with plenty of material," admits Selcuk Erdem, one of Penguen's editors, scribbling an image of Mr Erdogan in seconds.

The problem is that Turkey's president isn't laughing.

Under Recep Tayyip Erdogan's 12 years in office - first as prime minister, now as president - Penguen has been sued a number of times, including by Mr Erdogan himself for portraying him as different animals.

The latest case came over a recent front cover.

The president is depicted in front of his new, controversially extravagant palace.

"We could at least have sacrificed a journalist for the inauguration," says Mr Erdogan, with connotations of an Islamic ritual.

The man welcoming him is shown buttoning a suit jacket with a gesture that was deemed to suggest Mr Erdogan is homosexual.

A complaint was filed with the prosecutor, backed up by Mr Erdogan's lawyers, on the basis of "insulting the president".

The two Penguen cartoonists were sentenced to 14 months in prison.

It was reduced to 11 months for "good conduct" and then commuted to a fine of 14,000 Turkish lira ($5,350; £3,630).

'No sense of humour'

"We were very sorry - sad actually," says Selcuk Erdem, "not as cartoonists but as citizens, because someone going to court due to a cartoon is a very sad thing."

He insists that the gesture was misinterpreted and that his liberal publication would never joke about sexuality.

Selcuk Erdem says Penguen will carry on as before

Mr Erdogan and his government "don't have a sense of humour", says Mr Erdem.

"They don't want - or like - freedom of speech or criticism. We'll carry on drawing cartoons. We don't insult anyone - and worrying about court cases will lead to censorship in your mind, which is something we don't want."

Turkey's hard line on insults:

Between August 2014 and March 2015, 236 people investigated for "insulting the head of state"; 105 indicted; eight formally arrested

Between July and December 2014 (Recep Tayyip Erdogan's presidency), Turkey filed 477 requests to Twitter for removal of content, over five times more than any other country and an increase of 156% on the first half of the year

Reporters Without Borders places Turkey 149th of 180 countries in the press freedom index

During Mr Erdogan's time in office (Prime Minister 2003-14, President from 2014), 63 journalists have been sentenced to a total of 32 years in prison, with collective fines of $128,000

Article 299 of the Turkish penal code states that anybody who insults the president of the republic can face a prison term of up to four years. This sentence can be increased by a sixth if committed publicly; and a third if committed by press or media

In seven months over 230 people have been investigated for insulting the Turkish President, as Mark Lowen reports

Penguen is just one of a growing number of such cases.

Between Recep Tayyip Erdogan's election as president last August and March this year, 236 people were investigated for insulting him, according to figures from the Ministry of Justice. Of those, 105 were formally indicted.

The cases are initiated by individuals or lawyers, not by the president, but are often backed by his legal team.

A wide range of people have been hit by the charge, from writers to artists, journalists to protesters.

A 16-year-old boy was indicted earlier this year for calling the president a thief during a demonstration. He could be jailed for up to four years if convicted.

Even a former Miss Turkey has faced the charge, external, for posting a poem deemed to insult the president on her Instagram account.

Twitter 'menace'

Since 1926, Turkey's penal code has contained the article - number 299 - outlawing insulting the head of state. But in practice it was rarely used before Mr Erdogan's time in office.

Turkish authorities are sending out the message to be careful criticising the president, says Murat Onok

Murat Onok, a law professor at Istanbul's Koc University, believes pressure is being exerted on the judiciary to fall in line.

"Judges and prosecutors are appointed by a board on which the government has members," he says. "There's the feeling that if you adopt unpalatable decisions, you may be appointed elsewhere.

"The European Court of Human Rights states that members of the press enjoy the greatest protection," he says, "and the extent of tolerable criticism is very wide.

"Turkish authorities are either unaware of that, which isn't likely, or are choosing to ignore it. The message conveyed is: be careful with criticising Erdogan. And without freedom of speech, we cannot talk of a democracy."

Many of the cases are now sparked by Twitter, which the president has called "a menace".

Last week, the site was temporarily blocked by the Turkish government until photographs of a prosecutor taken hostage were removed - the second such block in a year.

Those targeted for their tweets include a former television journalist, Sedef Kabas. In one, she made reference to a massive corruption probe against the political establishment, including Mr Erdogan, which had been shelved by a government-appointed judge.

"Never forget the name of the judge who dropped the investigation," she wrote on Twitter.

The following day, police turned up at her house, confiscated her laptop and phone, and she was charged.

She could face a sentence of up to five years for her tweet and another four years for making police wait at her front door.

Former television journalist Sedef Kabas could face a prison sentence

Criticism v insults

"Those who back the governing party are free to insult and use defamatory language, while those critical of what's happening are suffering," she tells me.

"They're trying to polarise people as religious and non-religious, pro- and anti-Erdogan - and are embedding hatred in people. He's passing the message to his supporters: if you hate them, you'll support me more adamantly. War is being used as a tool to receive more support."

We asked the governing AK Party for interviews but were refused. There is the sense of a nervous balance in the run-up to June's general election.

But Ismail Caglar from the pro-government think tank Seta says it is correct that the head of state is protected in this way.

"In a democracy, people have the right to criticise - but there must be a line between criticising and insulting. We can discuss if the line is in the right place. But Mr Erdogan is by far the most insulted head of state in Turkey," he says.

"That's why public prosecutors are using the law more regularly for him."

Politics everywhere is a rough game: insults fly, reputations fall.

But, it seems, in today's Turkey, some skins are thicker than others.

- Published6 April 2015

- Published26 December 2014

- Published10 August 2014