Surveillance law prompts unease in France

- Published

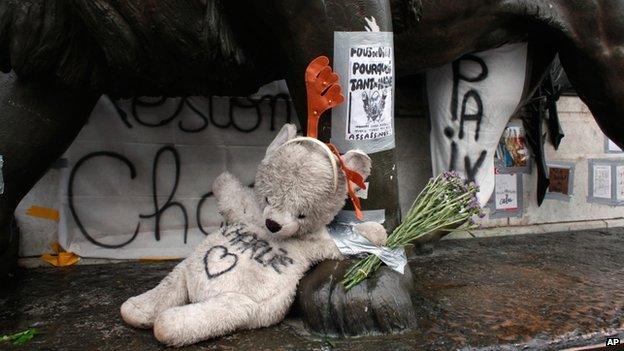

The Charlie Hebdo attack has left a lasting legacy in France

A new French law to beef up intelligence-gathering in the face of Jihadist violence is being opposed by an alliance of internet operators, defenders of civil liberties, journalists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

They say it is a dangerous extension of government power that authorises mass surveillance and threatens the independence of the digital economy.

One place the law does not face opposition - at least not in any significant measure - is the French parliament.

On Tuesday, the text goes to a vote in the National Assembly, where it is assured of a comfortable majority.

Most members of the opposition UMP have said they are in favour, and among the ruling Socialists there are few discordant voices.

Thanks to a fast-track procedure chosen after the Paris attacks in January, the law will go quickly before the Senate and should be on the statute books by July.

The political consensus is what remains of the "spirit of 11 January" - the mass demonstration of national unity triggered by January's Islamist terror.

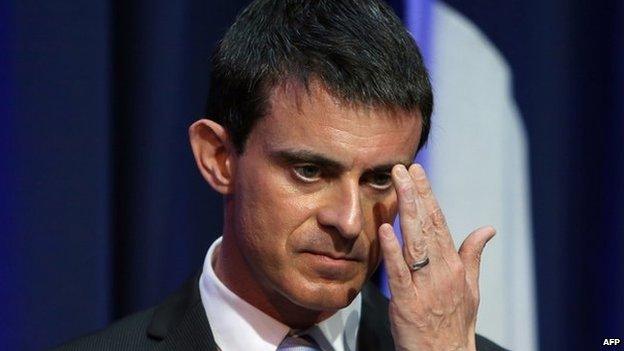

When Prime Minister Manuel Valls assured that the new law "has no resemblance to the Patriot Act, external" in the US and "offers concrete guarantees for our compatriots such as they have never had before in the matter of intelligence-gathering", MPs showed little inclination to argue.

Increasing doubts

Only a handful of deputies aired the doubts that are increasingly being heard in the extra-parliamentary sphere.

Manuel Valls has tried to reassure doubters that the new law would not be misused

One dissident Socialist, Pouria Amirshahi, warned that the context - the aftermath of the Charlie-Hebdo and HyperCacher killings - made it impossible to debate the law with due objectivity.

"Today if you express the slightest reserve over the text, you are practically accused of abetting terrorism," he said.

And it was left - oddly - to the Front National's Marion Marechal Le Pen to make the case for civil liberties.

"I cannot vote for this law because I cannot tell the French that their security comes at a cost to their freedom," she said.

The new law is officially intended to update the legislative framework inside which the security services do their work, taking account of the latest changes in technology.

Main provisions of the new law:

Define the purposes for which secret intelligence-gathering may be used

Set up a supervisory body, the National Commission for Control of Intelligence Techniques (CNCTR), with wider rules of operation

Authorise new methods, such as the bulk collection of metadata via internet providers

But on all three main points of the new law, the voices of concern are increasingly loud.

The text of the law lays out a series of areas in which France's six different security agencies may act.

Some of these are uncontroversial, such as "prevention of terrorism" and "national defence".

Confused implications

But what, say critics, of "major foreign policy interests"? Does that allow spying on opposition movements in other countries?

Or "industrial and scientific interests"? Would that allow agents to eavesdrop on journalists investigating major French companies?

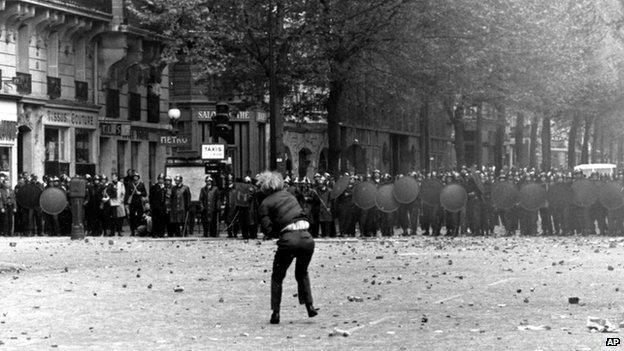

Could the law have been used against the 1968 student protesters?

The biggest confusion is over the nebulous expression "Prevention of attacks on the Republican form of institutions".

Pierre Lellouche - one of the few UMP deputies to oppose the text - says this could in theory have been used against the students in May 1968 or protesters in the general strike of 1995.

As for the new CNCTR, it will - according to the government - have extra powers to control electronic eavesdropping and act for aggrieved citizens.

It will have the right to launch investigations with access to classified documents and take cases of abuse to the State Council (France's highest administrative court).

But sceptics say these powers are meaningless.

Though intelligence agencies will have to present plans for approval to the CNCTR, its advice is non-binding because it can be over-ruled by the prime minister.

In addition, there are provisions in the law for emergency surveillance that bypass the CNCTR altogether, while citizens who want to go to court will in practice find it almost impossible to establish grounds for action.

There are worries about new listening devices such as IMSI-catchers, the briefcase-sized computers that by replicating a relay-station sweep up all mobile calls in the vicinity.

But by far the loudest opposition - because it comes from commercial interests as well as rights groups - is over internet-based data collection.

The law will allow intelligence-gatherers to install so-called "black boxes" on internet service providers (ISPs).

Pierre Lellouche is concerned at the language used to draft the law

Using a computer algorithm, these can trawl through billions of communications in search of suspicious activity that can then be analysed more thoroughly.

Government insistence that there is no mass intrusion of privacy because the information initially gleaned is all "metadata" - ie dates, times and places rather than actual content - has failed to convince opponents.

The internet company Mozilla is the latest to join the campaign.

In a statement, it said the government proposals "threaten internet infrastructure, user privacy, and data security".

A group of digital start-ups called NiPigeonsNiEspions (Neither suckers nor spies) has warned that some companies could relocate outside France because of the loss of credibility among foreign partners.

"Putting the internet under massive surveillance will undermine France's digital future, along with its jobs and hope for the French economy," it says.

No distinctions

And defenders of civil liberties say in a petition that the new system would "hoover up without distinction everything which appears on the French web".

"Contrary to the denials of the government, it is indeed generalised surveillance," the petition says.

Adrienne Charnet, of the group La Quadrature du Net (Squaring the Net), said: "The whole population will be profiled and then according to some unknown criteria - Do I encrypt my mail? Do I know the wrong person? Is my behaviour abnormal? - I can be declared suspect.

"It is also ludicrous to say the metadata is not private. These days metadata can say as much about my habits as the inside of a message does."

President Francois Hollande has now said that the text will be brought before the Constitutional Council (the august body which rules on the constitutionality of laws), which may well insist on some changes.

It is an odd initiative because as head of state he chaired the cabinet meeting where the text was first approved and so presumably believed back then that it was in order. Normally it is parliamentary opponents who challenge aspects of a new law.

But it is a sign that the campaign is having an effect.

Parliamentary opposition may have been hushed by the post-Charlie urge for consensus.

But in the land, the doubters are taking the lead.