Do fascist links discredit architect Le Corbusier?

- Published

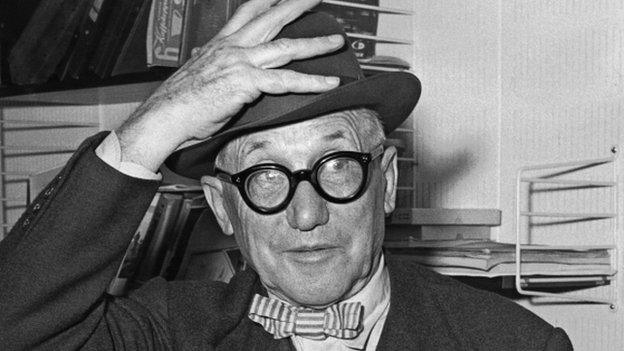

Le Corbusier is both an influential and controversial figure

Two new books on the modernist architect Le Corbusier have accused him of fascist and anti-Semitic views.

The publications coincided with the opening of a new exhibition, external profiling the artist at Paris's Pompidou Centre this week.

The timing has highlighted a long-running tension colouring the legacy of some of France's 20th Century heroes.

It is the kind of declaration guaranteed to grab headlines here.

One of France's best-known creative minds; the man credited as a pioneer of modern architecture was, says author Xavier de Jarcy, an "outright fascist".

New evidence from the artist's personal records, says Mr de Jarcy, led him to conclude in his new book (Le Corbusier: A French Fascism) that the architect's sympathies for fascism were much stronger than previously thought.

"Personally I was very shocked," he told me.

"I found it hard to accept. You need time to absorb that kind of information."

Deeper ties

Le Corbusier, born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret in 1887, moved to France from Switzerland at the age of 20 and later became a French citizen.

Some links to France's war-time government are well-known, but Mr de Jarcy says the new research shows much deeper ties.

Corbusierhaus in Berlin: one of the architect's signature works

"I discovered he was a member of a militant fascist group," he says.

"And he published around 20 articles which were clearly fascist in nature, where he declared himself in favour of a corporatist state on the model of Mussolini.

"There are also several witness statements from other group members, from his doctor who was a close friend, and from other militants."

Le Corbusier's artistic legacy is currently being celebrated in a big new exhibition at France's Pompidou Centre, which has come under fire for not fully reflecting the debate around his political views.

Frederic Migayrou, one of the curators of the exhibition, says the show was three years in the making, and the lack of discussion about Le Corbusier's politics has nothing to do with censorship, or avoidance of the issue.

The new books, he says, are acting "like tabloids - surfing on the 50th anniversary of the artist's death".

"They're just trying to create a media event," he told me.

"All the quotations on racism or fascism came from extracts of his private correspondence - he never published anything, nor made any public declaration against Jews.

"It's absurd. Le Corbusier was also in contact with many architects close to communism [and] people thought he was a communist in exactly the same way."

Ambiguous politics

So what is the truth about Le Corbusier?

Dr Caroline Levitt from Britain's Courtauld Institute says the commonly accepted fudge is that Le Corbusier had "ambiguous politics". And in some ways, she says, they were just that.

The High Court building in Chandigarh

"His politics tended to shift," she told me.

"He was more of an ideologist than a politician. He was interested in the potential of architecture - what it could do."

And it wasn't unusual for artists from that period to be labelled both communist and fascist, she says, and what made Le Corbusier so easily appropriated by both sides is his insistence on purification and classicism.

"He was trying to wipe out the troubled art of a troubled era, and suggest a life of order and clarity," she said.

"That's very appropriable by the Right. But it was also about shaking up the established ideas of the bourgeoisie, which is more akin to ideas of the Left."

What isn't often talked about - or is consigned to a couple of lines - says Dr Levitt, is the work done by Le Corbusier for France's Vichy government in the early 1940s, drawing up city plans for Algiers.

France's art establishment is often criticised for its close-door elitism, but it was the Pompidou Centre that covered Le Corbusier's association with the Vichy regime in an exhibition 25 years ago.

"Since then," says author Xavier de Jarcy, "Le Corbusier has become a marketing product, and he needs a presentable image. There are lots of shadowy areas when it comes to the actions of certain French artists from that period, but people don't really talk about it."

Art and politics

The BBC's Arts Editor Will Gompertz says these kinds of political tensions in the French art world can be traced back at least as far as the mid-19th Century, to the scandal surrounding the Dreyfus affair, when a Jewish soldier in the French army was made a scapegoat for a crime he didn't commit.

"There's a famous incident around the Dreyfus Affair, which split the avant-garde art world down the middle," he says, "with Degas and Cezanne taking an anti-Semitic line, and Pissaro and Monet siding with Dreyfus.

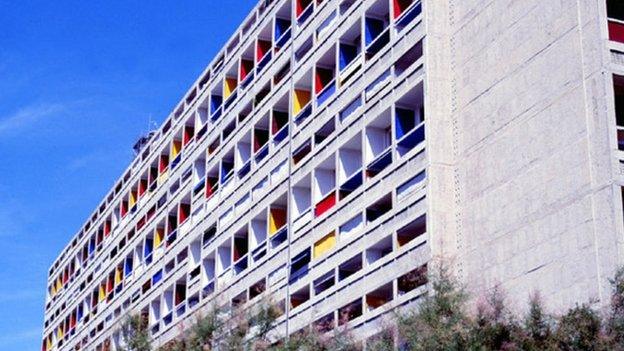

La Cite Radieuse, Marseille: An iconic work

La Cite Radieuse, Marseille

Le Corbusier developed a residential housing principle called Unité d'Habitation.

He thought the tower block was the solution for rehousing the masses that had been displaced during World War Two.

The most famous example was La Cite Radieuse (Radiant City) in Marseille, which is often credited for inspiring the Brutalist style of architecture prevalent in the 1960s.

The building, made of rough-cast concrete, has 337 apartments over 12 floors, all suspended on large pillars, and arranged around the concept of "internal streets". It also has sports, medical and educational facilities, a hotel and a restaurant.

It is pending designation as a World Heritage site by Unesco.

"It was an issue which rumbled through World War One and Two."

And when it comes to the issue of Le Corbusier, he says, there is a much wider relationship between the worlds of art and politics.

"Modernism as a concept has an awkward relationship with fascism. If you look at Brutalist, Fascist and Modernist architecture, there's a clear relationship.

"Although Hitler and the Nazi high command vilified modern art, they also drew a great deal of their aesthetic from it."

Frederic Migayrou from the Pompidou Centre vehemently disagrees.

"This is a manipulation," he says.

"We can't assimilate the work of Le Corbusier, and Modernism, and Totalitarianism - it's absolutely a false idea."

As for the charge that his institution is helping to draw a veil over Le Corbusier's political activities, Mr Migayrou says the Pompidou Centre is planning a major symposium next year, specifically to debate the issue.

"Things are changing," Xavier de Jarcy concedes.

"It's a step forward."