Power struggle in Macedonia

- Published

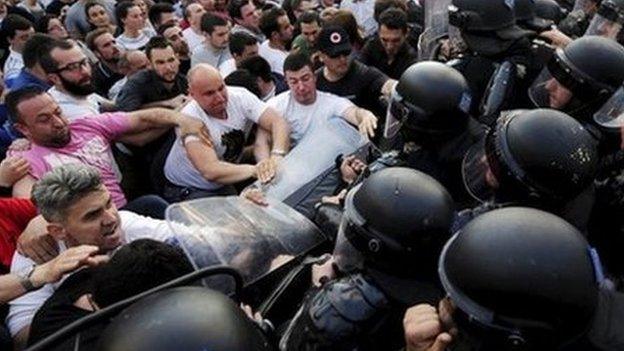

Riot police clashed with thousands of protesters in Skopje over the alleged cover-up of the death of a man in 2011

Outside the Balkans, Macedonia is rarely on the radar. But the violence that erupted outside government buildings has brought home the scale of the country's crisis.

Dozens of people were hurt as protesters took to the streets on Wednesday amid claims of a government cover-up.

Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski took power in 2006. Three elections since then, most recently in 2014, have returned his VMRO-DPMNE party to power in a succession of coalition governments.

Wire-taps

Mr Gruevski has certainly made his mark - most visibly on the capital, Skopje. A policy of "antiquisation" aimed to recast the city as the cradle of civilisation has resulted in a frenzy of construction.

Dozens of neo-classical buildings and scores of statues were erected in just a few years, transforming the city.

Critics accuse the government of being heavy-handed with those who oppose building projects in Skopje

But a difference in aesthetic preferences was not the only thing which upset critics. They also accused the authorities of being heavy-handed towards opponents of the construction projects.

Now the political opposition is accusing Mr Gruevski and his government of intolerance towards all forms of dissent. The allegations include vote-rigging, bribery and making illicit recordings of more than 20,000 people.

Since February, opposition leader Zoran Zaev has been releasing leaked recordings which he says were provided by members of the intelligence services alarmed by the government's apparently authoritarian leanings.

'Foreign intelligence'

"After nine years of leading the country, they need to control everything," he told the BBC. "They're targeting the opposition, journalists, businesses and ambassadors. We need help from the EU and international friends."

Several MEPs have brokered talks in Brussels between the government and the opposition, while the US has called for a "credible" investigation into the wire-tapping allegations.

Nonetheless, Mr Zaev has found himself facing criminal charges in Macedonia for releasing the recordings.

The government says that Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski has also been a victim of wire-tapping

Foreign Minister Nikola Poposki admitted that the affair had damaged the country's international image. But he insisted that Mr Gruevski was a victim of the secret recordings rather than the person behind them.

"Why would Gruevski tap himself?" he asked the BBC.

"There is foreign intelligence in this scheme. There is no proof of who the foreign power is - but the people in the affair have admitted that a foreign power is involved," he said, referring to Mr Zaev's comments during a conversation with the prime minister.

The opposition leader is certainly no angel. He was given a presidential pardon in 2008 after being arrested over a land scandal, although he insisted the charges were politically-motivated.

His current actions could easily be interpreted as an attempt to overturn a democratic election for personal gain.

But, at least in Skopje, it is not hard to find people who appreciate his challenge to the government.

Opposition leader Zoran Zaev is facing criminal charges in Macedonia for releasing the secret recordings

"I don't like Zaev, but I like what he's doing for my country," one civil society activist told the BBC.

Among long-term Balkan-watchers, the response is more of a resigned shrug.

Eric Gordy, a senior lecturer at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London, says recent events amount to local business as usual.

"It's something to be worried about if it escalates to the use of violence to stay in power - which is not impossible, but also not likely. But having corrupt governments in the region that abuse people's rights - that's the normal situation."

- Published10 June 2024

- Published6 May 2015

- Published10 February 2015

- Published6 October 2014