Why Ireland's holding a same-sex marriage referendum

- Published

Voters in the Republic of Ireland will go to the polls on Friday to decide whether to enshrine marriage equality in the constitution.

Ireland will be the first country to use a national referendum to extend marriage rights to gay couples.

The signs are that voters will take the opportunity to move towards a more open and pluralistic society.

Many question the wisdom of putting the rights of a minority up to a vote of a majority.

Furthermore, there is some dispute about whether a referendum is legally necessary; after all, other countries have simply changed the law.

But Ireland has quite an extensive written constitution and it can be amended only by process of national referendum.

The constitution does not define marriage as being between a man and a woman, but there is uncertainty over whether any legislation extending marriage rights could be open to legal challenge in the Supreme Court.

It is likely that a cautious government opted for direct engagement with the electorate by referendum rather than running the gauntlet of producing legislation on marriage equality, which could have been struck down by the courts and then would have needed to be put to a referendum in any case.

In 2010, the government enacted civil partnership legislation, which provided legal recognition of the partnerships of gay couples.

But there are some important differences between civil partnership and marriage, the critical one being that marriage is protected in the constitution while civil partnership is not. It could be removed through the same legislative process by which it was introduced.

'Our generation'

This referendum has been in the pipeline since the Fine Gael-Labour coalition government took office in 2011, when the Deputy Prime Minister, or Tánaiste, Eamon Gilmore called it: "The civil rights issue of our generation."

A constitutional convention established by the government considered the specifics of the proposal on extending marriage rights.

The convention voted in favour of the proposal and the date for the referendum was agreed earlier this year.

The No vote uses traditional family models in its campaigning

All political parties in parliament have endorsed the marriage equality proposal, with just five of the 226 members of parliament publicly announcing they will vote against.

Opinion polls are also predicting a vote in favour - a year ago, they pointed to a Yes vote of close to 80%.

Since then, the margin has tightened but three weekend opinion polls indicated that the proposal should still pass with a reasonable margin of support - probably in the region of 60%.

The referendum campaign has been slightly more respectful than some of the deeply divisive and nasty social policy referendums on divorce and abortion in the 1980s and 1990s, but many of the same campaigners are still on the field, particularly on the No side.

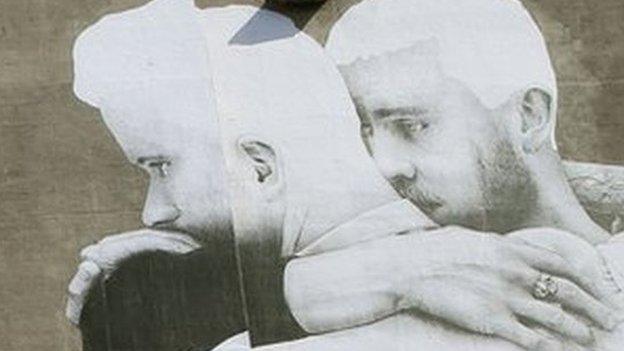

A Yes vote campaign poster in Dublin

The Yes campaign is led by an active, crowdfunded and very effective referendum umbrella group, Yes Equality, and is joined by all of the political parties.

Church's declining influence

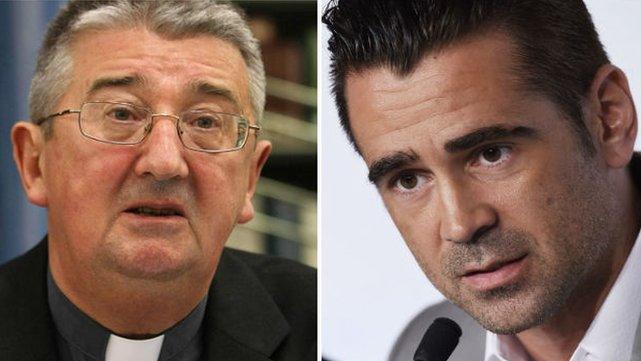

The No campaign has been spearheaded by a number of Catholic lay civil society groups, with the institutional Catholic Church playing a relatively low-key role in the background.

The Catholic Church, once a dominant player on the political scene, has seen its role and influence diminished greatly by decades of child abuse scandals.

In a poll last weekend, we found that some 35% still rely on the Church as a source of influence in their vote.

This figure may seem high by international standards, but it marks a significant diminution of the influence of the Catholic Church.

The No side relies heavily on traditional models of the family and in common with referendums that touched on family issues in the past, it speaks to the grave societal dangers of moving away from family values and a society built on the core, heterosexual married family unit with children.

In contrast, the Yes campaign has concentrated on equality as the central plank of its argument and has used personal testimony from high-profile gay citizens and children of gay parents to great effect in the many radio and TV debates.

Irish society has become more secular over the past few decades and indeed constitutional changes have often lagged overall attitudes on social and moral issues.

Contentious debates on divorce in the 1980s and 1990s faded very quickly when divorce was passed by referendum in 1995. Indeed, successive surveys have demonstrated that divorce is now a largely uncontroversial issue.

Gay marriage timeline: Years that same-sex marriage approved

Netherlands (2001)

Belgium (2003)

Canada (2005)

Spain (2005)

South Africa (2006)

Norway (2009)

Sweden (2009)

Argentina (2010)

Iceland (2010)

Portugal (2010)

Denmark (2012)

Brazil (2013)

England & Wales (2013)

France (2013)

New Zealand (2013)

Uruguay (2013)

Luxembourg (2014)

Scotland (2014 )

Countries where same-sex marriage legal in some jurisdictions

United States (2003)

Mexico (2009)

There has been movement in attitudes to abortion although it is still contentious. However, voters have twice rejected referendum proposals (1992 and 2002) aimed at making abortion provision stricter.

Eventually, a brave government will have to run the gauntlet of the vocal but increasingly minority conservative right and offer a referendum proposal on abortion, which would liberalise it, rather than restrict it.

Ireland has long been seen as a conservative Catholic country - after all homosexuality was decriminalised only in 1993 after a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights.

However, the country has experienced rapid social and political change since the 1970s and all the indications are that it will take a further step away from its conservative past on Friday.

Dr Jane Suiter, external is director of the Institute for Future Media and Journalism at Dublin City University and Dr Theresa Reidy, external is a lecturer in the department of government at University College Cork.

- Published21 May 2015

- Published1 May 2015

- Published1 September 2014

- Published11 June 2013

- Published28 March 2014

- Published13 December 2013