Cars and shoe boxes: How Greeks cope with economic crisis

- Published

Greeks rich and poor have turned to unorthodox ways of preserving their wealth

As the race to solve Greece's debt crisis struggles on, the uncertainty of what is to come has hit ordinary Greeks.

With billions of euros withdrawn from Greek banks this week alone, the BBC found out how people are handling their money, and what they predict for the future.

"My in-laws are saving gold sovereigns. We are going back to the 1940s," says Ilia Piatroo, a part-time translator.

Many people in Greece still have memories of World War Two. Some of the actions they took to survive it, Ms Piatroo says, are being repeated.

"My parents grew up during the occupation and at the time the only things that had value were food and gold. Now food has no value, so now they invest in gold."

Greek pensioners have been hit particularly hard by the crisis

Ms Piatroo is leaving her money in the bank. She says that few of the younger generation have money left to transfer abroad or hide.

Nevertheless, she says that she can understand why people are pulling money out of their banks and hiding it under their mattresses.

"We are afraid and we don't trust anyone to protect us anymore," she says.

'Panic effect'

"If people have money in the banks, it makes sense individually to take money out of the banking system," says Vassilis Monastiriotis, an expert in political economy.

"If you have 1,000 or 2,000 euros in the bank, some people will think that they might as well take it out."

He says that the "panic effect" becomes a kind of self-fulfilling prophesy: "It becomes, as we say, individually optimal for people to do it."

"We normally see pensioners queuing at the bank when pensions are being paid but it is out of the ordinary to see them queuing on days in the middle of the month. It is a visible sign," says Platon Tinios, a lecturer in economics at the University of Piraeus.

Greek banks - like this one in Athens - have seen a surge of withdrawals

He says that most people with larger deposits have removed their money already.

"The smarter money has gone. What we are witnessing now are the small savers and people whose links with the banks are to do with their monthly pay checks."

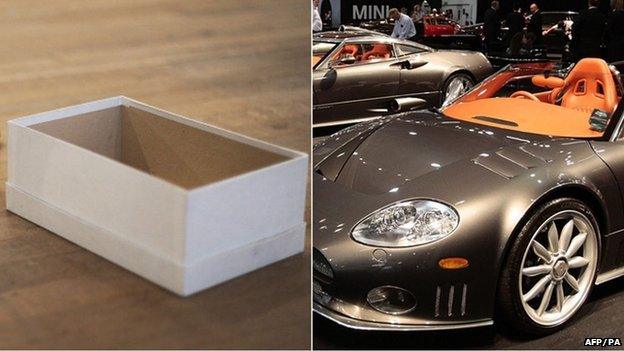

Shoe boxes

Some of these people are preparing to take the same risks they did in previous economic scares.

"I know people who took a fair amount of money, put it into two shoe boxes and buried them in an olive grove. They went back and found one but are still digging to find the other," he says.

As Ms Piatroo says, gold is a traditional investment for those who can afford it but Greeks are also choosing to spend their money on other assets.

"Over the past few months there has been an increase of new cars in circulation," says Mr Tinios.

Mr Monastiriotis thinks that some people are being driven by fear that capital control measures could be introduced.

A mural called Death of Euro. Will Greece bid goodbye to the single currency?

This is despite the fact that the banks will have tested their systems in preparation.

"If it's implemented, basically there will be big sections of society that will be largely unaffected. But small business would suffer because they would not be able to do day-to-day transactions."

Panos Tsakloglou, an economist at Athens University, says Greeks are afraid their government will not strike a deal with its creditors.

"People are moving their currency abroad, keeping at home or buying foreign bonds and assets."

If the negotiations fail completely, he says, the "days of EU membership are numbered".

And he warns that the rushed withdrawals from the banks may only be the first indications of a real bank run still to come.