Greece debt crisis: Why should I care?

- Published

After months of often bitter talks, the Greek debt crisis could finally reach a resolution this weekend, after Athens submitted fresh proposals aimed at securing a third bailout and averting a possible exit from the euro.

But with Greece making up just 2% of the eurozone economy, would a "Grexit" even matter? Here are five reasons.

1. 'Grexit' could be disastrous for Greece

Could a Grexit boost the far-right Golden Dawn party?

There are no guarantees that a Greek economy freed of the eurozone shackles would flourish.

The Bank of Greece has painted a very bleak picture of what Grexit might mean - a deep recession, with soaring unemployment and slumping incomes.

Ordinary Greeks would find their savings devalued. Greece would find itself an outcast on international credit markets, making a swift recovery even more unlikely.

It would have to introduce a new currency, bringing further instability.

Greece has a history of coups and there are fears leaving the euro could prove politically debilitating.

Voters turned to Syriza amid dissatisfaction with traditional parties. If Syriza leads Greece out of the euro, or gets a deal deemed unacceptable, voters may turn even further from the mainstream, and towards parties like the Communists or far-right Golden Dawn.

2. Whatever the outcome, it will have a knock-on effect in other countries

Other anti-austerity parties could profit from any Syriza gains

European politics is so intertwined it is hard to imagine a scenario that cannot be spun to the advantage of at least one of its actors.

The progress of Greek Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, is being closely watched by other anti-austerity parties like Spain's Podemos.

The party made gains in local elections in May, and success for Mr Tsipras would be a fillip for it ahead of general elections later this year.

If Germany agrees to a write-down of Greek debt, German Chancellor Angela Merkel could face a backlash from voters unhappy about Greece being let off the hook.

And for anti-EU parties such as France's National Front, or Britain's Ukip, the crisis strengthens their argument that European integration is ultimately doomed.

Another factor is that Greece, along with Italy, has borne the brunt of the surge in numbers of migrants from the Middle East and North Africa.

A Greece out of the euro would be less able - and less inclined - to co-operate on this issue. Greek Defence Minister Panos Kammenos has invoked this possibility by threatening to "flood" Europe with migrants if Greece was allowed to go bust.

3. The US is worried

Could a Grexit hand an advantage to Russia?

The US has largely sat on the sidelines of the crisis, but has still made its influence felt - some saw Washington's hands on the release of an IMF report backing Greek calls for debt relief.

While the US has expressed concern about the effects of a Grexit on the global economy, it also fears the growth of Russian influence on Europe.

Leaving the euro could force Greece to seek Russian aid - but it is not clear what Moscow's price may be.

Mr Tsipras has already threatened European unity over Russia's actions in Ukraine by calling for an end to sanctions.

Greece is also a Nato member, and the organisation has warned of "repercussions" if Greece leaves the euro.

"If Greece leaves, I'll bet you that in Moscow, this will be seen as confirmation of the Russian theory that the European Union is in decline and about to fall apart," Wolfgang Ischinger, a former German ambassador to the US told Bloomberg, external.

4. If Greece goes, others could follow

First Greece, next Portugal?

A key worry is that if Greece were to leave, it would start an irreversible domino effect.

Unlike the last Greek crisis, there are reasons to believe this would not happen - the EU has taken steps to isolate financial difficulties of one member state from the rest.

If Greece were to leave, it would be at a time when the European economy is recovering, softening the blow.

But given the inevitable uncertainty that would follow a Greek exit, as US Treasury Secretary Jack Lew put it, it would be a "mistake" to think there would be no contagion. Countries like Ireland and Portugal, previous recipients of bailout money, could be dragged back into crisis.

A Greek exit would change how the common currency project is seen.

The EU commission once described eurozone membership as "irrevocable," but Greece leaving would show that is no longer the case.

Louka Katseli, chair of the National Bank of Greece, said that would give the green light for the markets to attack weaker members of the currency grouping.

5. The global economy won't like it

Stock markets have been rattled by questions over Greece

Greece makes up a tiny part of the world economy - Jim O'Neill, former head of economics at Goldman Sachs, once calculated that China created an economy the size of Greece every three months.

But Greece's role in one of the world's major currencies means its exit is unlikely to be shrugged off.

Stock markets have slid and risen in line with speculation about whether a deal can be reached and are likely be further spooked by a Grexit.

Greece's creditors such as the European Central Bank and other European countries would also face immediate losses.

Even if Greece strikes a deal, its problems will not be solved overnight. Nor will all the criticisms of the single currency be answered. Further uncertainly seems unavoidable.

"The marriage may endure," says the Economist magazine, external - "but even more unhappily than before".

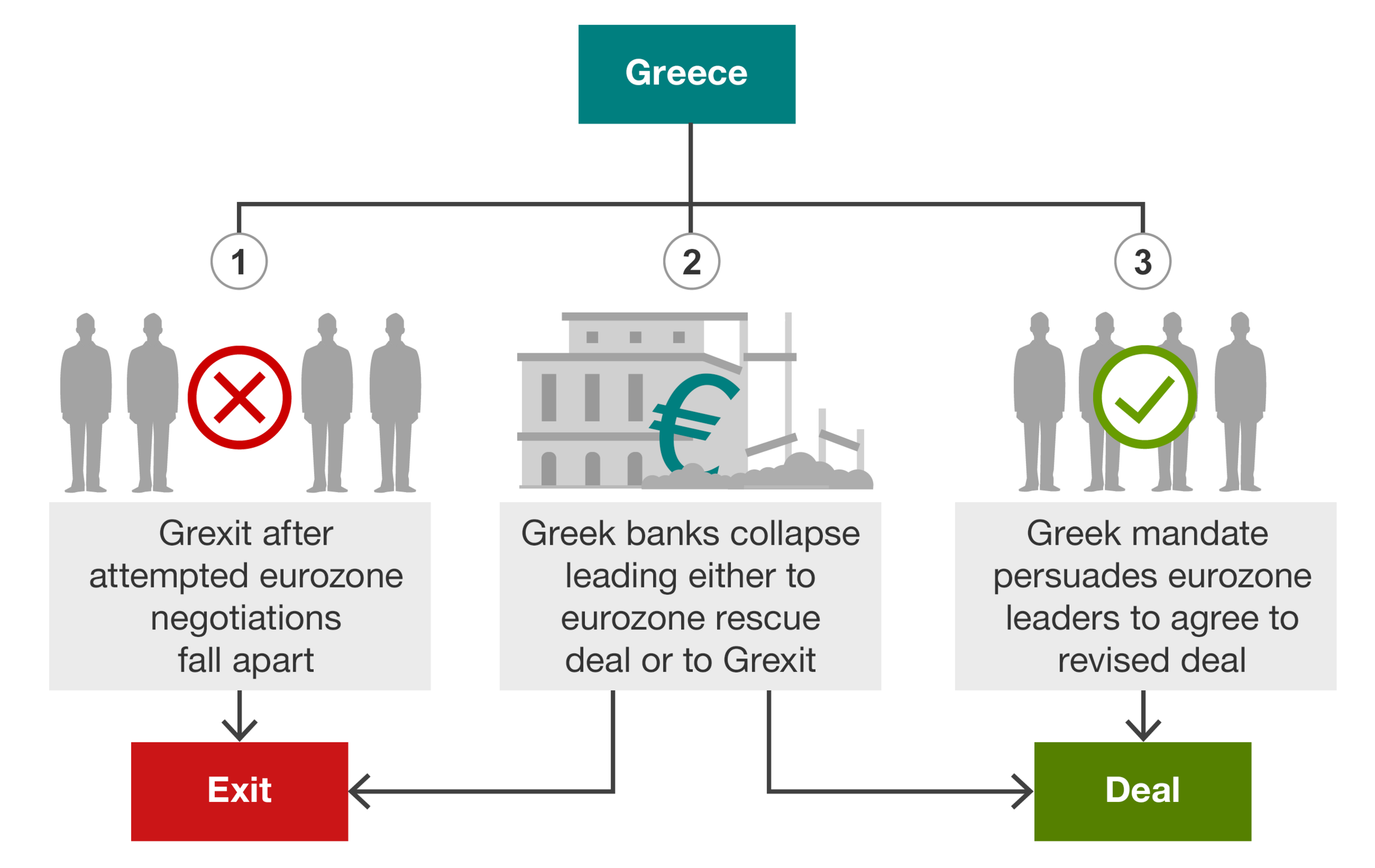

What could happen now?

There are at least three scenarios - but at the heart of each of them is what will happen to Greek banks and to the emergency cash funding provided by the European Central Bank (ECB).