Greek debt crisis: Tsipras may face impossible choice

- Published

Alexis Tsipras and his party are suspicious of Greece's creditors

Red lines - everyone has them, including Greece and its creditors.

Lines they can't cross. Commitments they say they can't break. But suddenly the red lines are everywhere.

A counter-proposal put forward by the creditor institutions, in response to Greece's offer of budget reforms, is full of them.

Put simply, Greece has offered to meet its budget targets mainly by raising taxes rather than cutting spending.

But the creditors - and the IMF in particular - say that is unacceptable.

They see it as a squeeze of a different kind, snuffing out any hope of economic growth.

So there is still pressure for more cuts in the pension system, and the abolition of a larger number of subsidies.

The Greek government may think it has given significant ground in its latest proposal. The creditors appear to be saying think again.

If the Greek parliament rejects a deal with Europe then Tsipras may have to consider his position

So the mood goes from bad to good and back again. In terms of absolute numbers, the distance between the two sides isn't huge. But the political gulf is significant.

And Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is caught between a rock and a hard place - between the promises he made to his voters back home, and the commitments the creditors insist he must respect.

But these negotiations aren't just about budget targets. The Greeks are also demanding that there has to be serious discussion of debt restructuring.

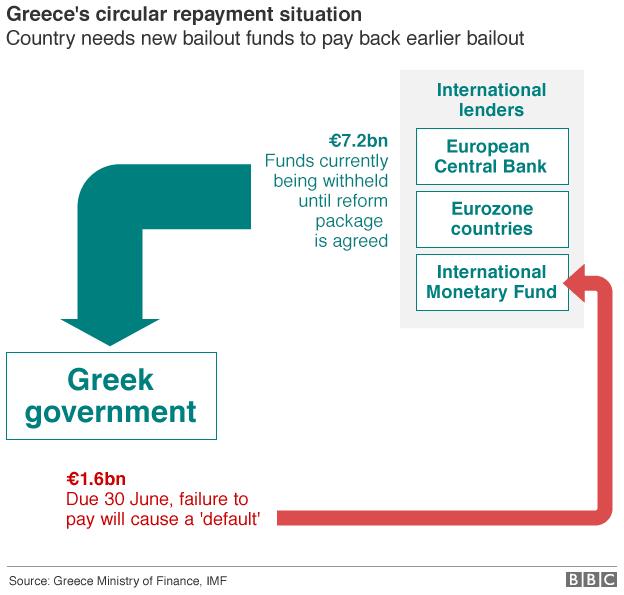

On that issue there is more sympathy from the IMF. But there is less from the European Central Bank and several eurozone countries.

'An impossible position'

One proposal is to transfer €27bn ($30bn; £19bn) of debt that Greece owes to the ECB into the ESM, the eurozone's permanent bailout fund.

It has a more gentle long-term repayment schedule, and lower rates of interest.

If Mr Tsipras can go home with a deal which feels terribly tough, but which includes promises to reduce the suffocating embrace of the debt burden, he has a chance of selling it.

But he's now saying publicly that perhaps the creditors don't want a deal, or that they are pandering to specific interests inside Greece.

That speaks to the suspicion within Syriza that the creditors are determined to put the prime minister in an impossible position.

If he puts an agreement to the vote in parliament and loses, he will have to resign.

And the EU's only government of the radical left would go with him.