Europe migrant crisis: How are countries coping?

- Published

Many migrants were blocked earlier in June at the French-Italian border

Europe's migration crisis affects EU member states in different ways - so it is proving difficult to agree on common rules.

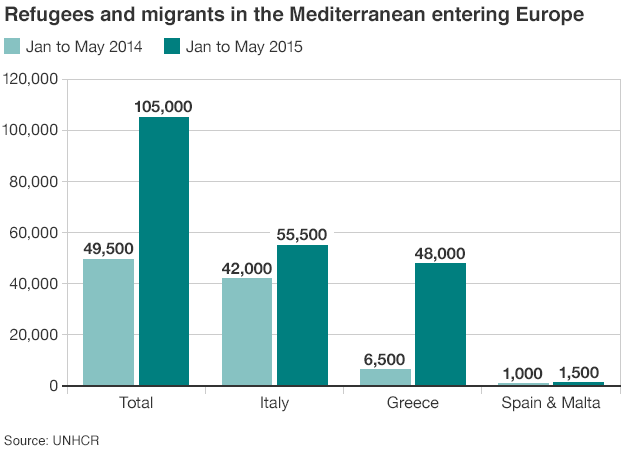

The influx of migrants into southern Europe has escalated, driven by the wars in Syria and Iraq, as well as conflict in many parts of Africa. More than 150,000 have arrived this year - far more than in the first half of last year.

The EU is struggling with shifting migration patterns, creating particular problems for individual countries. How are they coping?

Italy

Migrants pray as they arrive at a Belgian rescue boat off the coast of Sicily

For months Italy has been on the frontline of the crisis, as boatloads of desperate migrants risk their lives trying to reach Lampedusa or Sicily.

Last year Italy controversially reduced its naval patrols off war-torn Libya, telling its EU partners that they must contribute to efforts to stop the migrant boats coming.

After hundreds of migrants drowned off Lampedusa this year, the EU agreed to launch a joint naval operation to rescue migrants in distress. But aid agencies say patrols ought to cover a wide area on the high seas - not just the EU's territorial waters.

Italy says its EU partners must also share the burden of housing migrants and processing asylum claims.

Prime Minister Matteo Renzi voiced anger at East European leaders who rejected an EU plan for mandatory quotas to distribute migrants across the 28-nation bloc.

Recently France blocked hundreds of migrants at Ventimiglia, on the Italian border.

Many migrants staying at makeshift camps in Italy are desperate to move on to northern Europe.

Greece

How can EU address its migrant issue?

The boatloads of migrants heading for Greek islands have increased sharply this year.

Lesvos is a particular pressure point. Many of the migrants are Syrians, and many of them will be entitled to refugee status, having fled the civil war.

But Greece's reception centres are overcrowded and some are in a deplorable state.

Heavily indebted Greece, already unable to pay its bills, cannot cope with the influx. It has a massive backlog of asylum claims to process.

There is much hostility in Greece towards non-EU migrants, and many of them quickly try to move north via the Balkans to reach other EU countries.

In the current economic crisis many Greeks fear competition from foreigners for scarce jobs.

France

In recent years France has sent many poor Roma (Gypsies) back to Romania and Bulgaria, after they entered France illegally.

But now the French focus is on the growing numbers of migrants entering Europe from the Mediterranean. They include many sub-Saharan Africans, some of whom have camped out on the streets of Paris.

The latest pressure point is Calais, where about 3,000 irregular migrants are sleeping rough, getting little local help. They want to get to the UK - and pictures of them jumping on to UK-bound lorries triggered fresh British criticism of lax security at the French port.

France says the UK must provide more help to solve the Calais crisis.

UK

Migrants continue to try and board lorries bound for the United Kingdom in Calais

The UK's emphasis is on breaking up the people-smuggling networks - trying to tackle the problem before the migrants turn up in Europe.

UK politicians point out that the UK spends more than many other EU countries on development aid, which can help stem the flow of economic migrants from poor countries.

The UK and some other EU countries also want stronger EU efforts to send failed asylum seekers back. Last year the rate for sending migrants back was just 39%.

But the British debate has tended to focus on the Conservatives' ambition to reduce immigration from EU countries. The government wants to tighten the rules on migrants' social benefits, as a disincentive for would-be immigrants from the EU.

The UK is involved in the Mediterranean naval operation, but has opted out of the EU plan to relocate 40,000 asylum seekers from overcrowded migrant centres in Italy and Greece.

Germany

Germany will need immigrants to fill labour market gaps in the future

Germany has more asylum seekers than any other EU country. Its strong economy is a magnet for migrants desperate to start a new life.

But like other EU countries, Germany wants much better screening of migrants, to determine who has the skills that the German economy needs.

The birth rate in Germany, as in Italy, is low - so both countries will need immigrants to fill labour market gaps in future.

Germany has a tradition of welcoming migrants - after all, Turks, Yugoslavs and some other nationalities contributed greatly to Germany's post-war economic boom.

Germany and Austria support the EU plan for resettling asylum seekers. That contrasts with the reluctance of most East European countries to take in more migrants.

Germany has been the preferred destination of many Chechens, who fled Russia's bloody crackdown against separatist fighters.

Partly the East Europeans are worried that they could see an influx from Ukraine, where fighting continues between government troops and pro-Russian rebels.

But apart from Hungary and Bulgaria, the other eastern countries have relatively low rates of immigration.

Hungary

There has been a sharp rise in the number of migrants trying to enter Hungary

Tensions have risen between Hungary and neighbouring Austria recently, since Hungary announced that it would not take back migrants who had moved elsewhere in the EU.

Hungary now says it is a temporary measure, because of a sudden influx - not a violation of the EU's Dublin Regulation. That rule says the country where a migrant first arrives is responsible for handling the migrant's asylum claim.

This year Hungary has experienced a surge of migrants trying to enter from Serbia. It has announced plans to fence off the Serbian border.

Many of Hungary's recent immigrants are escaping dire poverty in Kosovo, and many of their asylum claims are likely to be rejected.

Hungary and Bulgaria are exempt from the new EU plan to relocate asylum-seekers across the EU.

Bulgaria, like Hungary, says it cannot cope with any more, as its reception centres are overcrowded.