What can Greece learn from Argentina's default experience?

- Published

A Greek exit from the eurozone could have far more negative consequences than many analysts realise, warns Domingo Cavallo, Argentina's Minister of the Economy at the time of that country's default in 2001.

Having been at the heart of government in Buenos Aires during the slow, inexorable slide to financial collapse, Mr Cavallo is attuned to the magnitude of the perils now facing the Greeks.

"Defaulting not only on the foreign debts but also on the domestic debts and all foreign contracts at the beginning of 2002 was really a tragedy for Argentina," he told the BBC's Newshour Extra programme.

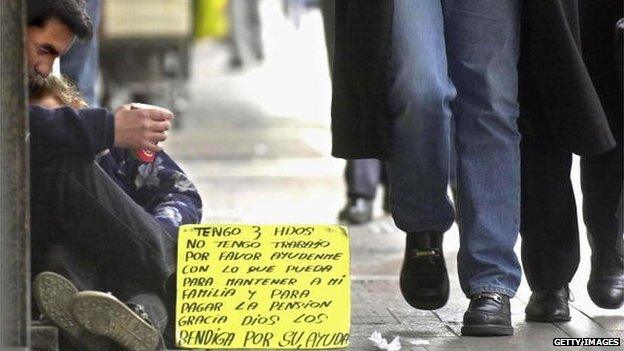

For many Argentines, the period following the default was ruinous: unemployment nearly doubled to more than 20%. Inflation, which had been vanquished in the 1990s, came back into the economy with a vengeance.

In the year after default, the country's gross domestic product (GDP) declined by 11%. And the poor economic performance had real consequences. The proportion of Argentines living in poverty rose above 50%.

Unemployment soared following Argentina's default

As it tried to balance the books, the government decreed that bank deposits be converted into pesos. In effect, the government had confiscated people's savings. Many people found themselves unable to pay bills such as their mortgage payments because they were denominated in dollars.

Powerful financial players also lost out. Private companies that had purchased utility companies on the basis that customers would pay their bills in dollar values found themselves out of pocket. Some took legal action that remains unresolved to this day.

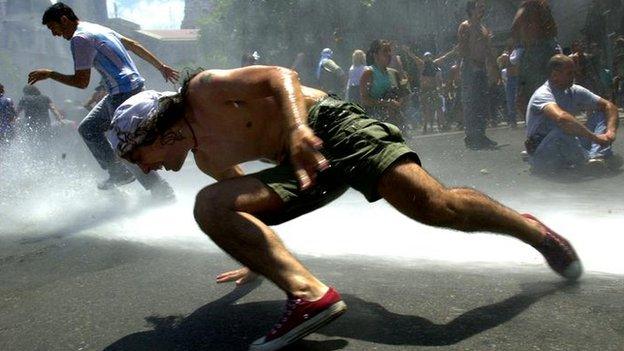

The turmoil on the markets spilt out onto the streets. Lost savings and fears for the future led to violent riots in which lives were lost. The consequent political instability led a whole series of senior politicians to resign.

Anti-government protesters took to the streets in Buenos Aires

But in some ways it could have been worse for Argentina. The country's traditionally vibrant agricultural sector was able to take advantage of the devalued currency.

And, by good fortune, the period after 2001 saw global agricultural prices shoot up, spurred on by Chinese demand. Argentine exports more than doubled between 2002 and 2006.

"Argentina recovered because of the huge improvement in the terms of trade that came from mid-2002 on," Mr Cavallo says. "The price of soya went up from $120 [£76] per tonne to $600 per tonne."

Argentina's economic struggles

Argentina is one of South America's largest economies. But it has also fallen prey to a boom-and-bust cycle.

A deep recession foreshadowed economic collapse in 2001, which left more than half the population living in poverty and triggered unrest. The country struggled with record debt defaults and currency devaluation.

By 2003 a recovery was under way and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed to a vital new loan. Since then, Argentina has restructured its massive debt, offering creditors new bonds for the defaulted ones, and has repaid its debt to the IMF.

But although the economy has been on the mend since 2001, Argentina again defaulted on its international debt in July 2014.

While some suggest Greece could experience a similar post-default recovery, there are reasons for believing that, in fact, it would not manage to emulate Argentina's export-led growth performance. Greece lacks a strong export sector that could take advantage of a devalued currency.

"Greece does not have a very strong or competitive manufacturing sector," says Dr Jill Hedges, of the research group Oxford Analytica. "Greece is not a trading nation."

While a return to a weakened drachma might encourage more foreign holidaymakers to go to Greece, it is far from clear that an improved and more vibrant tourism sector would be enough to produce a general economic recovery.

Furthermore, without pressure from Brussels and the IMF, Greece might be tempted to dodge some of the structural reforms that its creditors maintain are necessary for long-term growth. A lack of such reforms could reintroduce inflation into the Greek economy.

"How many years before they would see the light at the end of the tunnel?" asks financial expert Paul Blustein.

Mr Blustein, who wrote a book on the Argentine default, is now writing one on the crisis in Athens. "Greece would go through a horribly wretched period," he says.

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.