Greek debt crisis: Tsipras and his Greek gamble

- Published

Alexis Tsipras became prime minister in January

In making his calculations, the Greek Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, should be under no illusions - the rest of the eurozone wants him out.

When he unexpectedly sprung a referendum on his European partners, they were outraged and quickly ended negotiations.

Now, in places such as Berlin, Madrid and Helsinki, they spy an opportunity to rid themselves of a troublesome leader.

In Sunday's referendum, the rest of the eurozone are not bystanders - they intend to shape and influence the outcome.

It is a game they have played before.

In 2011, the then Greek Prime Minister, George Papandreou, announced he would put the bailout package to a referendum.

'Depressed madman'

He was summoned to a G20 meeting in Cannes and told by the other European leaders: "We cannot accept that."

President Nicolas Sarkozy referred to Mr Papandreou as a "madman" whose acts were those of a depressed man.

But anger soon turned to calculation.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel began redefining what the vote should be about.

The question, she said, should be: "Do you want to be in the euro or not?"

Mr Papandreou's downfall followed shortly after.

Five graphs that explain Greek crisis

In the current crisis, European leaders are lining up to define next Sunday's referendum.

"The Greeks don't have to say whether they love the PM more than [European Commission President Jean-Claude] Juncker," said the German Vice-Chancellor, Sigmar Gabriel, "but whether they want to stay in the single currency or not... it's 'Yes' or 'No' to staying in the euro."

The French Finance Minister, Michel Sapin, who has been conciliatory to the Greek government, said: "If Greece votes 'No', there is a risk of sliding towards a Greek exit from the euro."

The Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, said the referendum was "about the drachma versus the euro".

Rising tension

Alexis Tsipras believes a resounding 'No' vote will strengthen his hand.

He says it will be a "continuation of negotiations" by other means.

He and his colleagues in Syriza are trying to shape the poll as a vote on austerity.

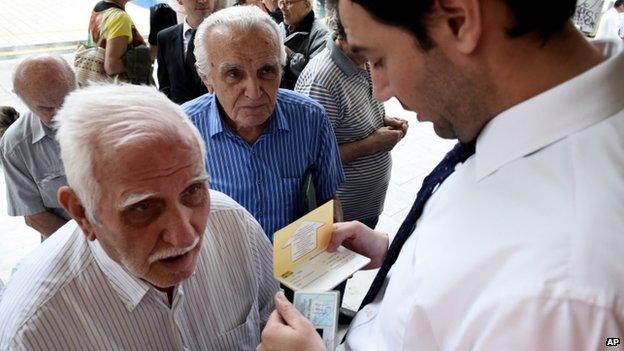

Pensioners were allowed to withdraw a one-off payment of €120

So when, on Tuesday, he requested a third bailout from the European Stability Mechanism, it was interpreted in Brussels as an indication of weakness, of increasing anxiety in Athens.

Mrs Merkel was quick to say: "Before a referendum, as planned, is carried out, we won't negotiate on anything new at all."

It almost seemed that the German chancellor now wanted the referendum.

Other European leaders believe that the queues at the cash machines, the confusion of pensioners awaiting their weekly payments, the fears that there will be a levy on deposits will all strengthen the hand of the 'Yes' campaign.

Inside the prime minister's office, at Maximos Mansion, there are reports of disputes and sharp arguments.

There is a growing awareness of the size of the gamble, of the high risks they have embraced.

Career on line

That is why it was not entirely unexpected when, on Wednesday, it was revealed that Mr Tsipras had sent a letter to Brussels accepting the bailout offer of 28 June with relatively minor conditions.

In recent days, Mr Tsipras seemed to understand his political future was on the line.

He said: "If the Greek people want to proceed with austerity plans in perpetuity... we will respect it, but we will not be the ones to carry it out."

There is much that remains, however, on Alexis Tsipras's side.

It would be foolish to underestimate just how many people's lives have been devastated by austerity and an economy that has collapsed 25% in five years.

There is also a defiant strain in the Greek character.

There are many Greeks who savour "resistance" and believe, as Mr Tsipras does, that the creditors have "asphyxiated" the Greek economy, that Greece was used as a kind of laboratory for austerity.

And then there is the continuing disdain for the previous government of Antonis Samaras, which lacked popular appeal.

But Brussels and Berlin will have been heartened by Tuesday's demonstration, with protesters holding banners that read: "Yes to Europe, Yes to the Euro."

What happens next?

1 July - Eurogroup - the finance ministers of the eurozone - holds a telephone conference to discuss new proposal from Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras

5 July - Referendum on creditors' proposals, which many say is effectively a vote on Greek membership of the eurozone

20 July - Greece must redeem €3.46bn of bonds held by the European Central Bank. If it fails to do so, the ECB can cut off Greece's access to emergency loans

They know the polls suggest that a strong majority of Greeks wants to stay in the eurozone.

That is precisely what Brussels wants this struggle to be about.

The president of the European Commission accused Mr Tsipras of playing "liar's poker" with the future of Europe.

In this game, either the Greek government has to back down or Europe will do everything it can to defeat him in the referendum on Sunday.