Greek debt crisis: What next for the European Union dream?

- Published

The flags of all the member countries reflected in the European Parliament building

In a European Union that's currently dominated by eye-popping debt figures, last-minute debt talks and sharp-tongued insults, some people are wondering what happened to the idealism behind the European project: the "European idea"?

Or, at least, some of those with a long memory have been wondering. For the past few years, as the EU has grappled with economic and migration crises, even the idea of a European idea has been largely absent from the debate, apart from often vague-sounding calls for solidarity.

In fact, many younger Europeans probably can't remember a time when the EU was anything other than a study in sustained crisis management.

"United in diversity" remains the EU's official motto. "United in adversity" may be a more appropriate one.

Not that there has seemed to be a great deal of unity of late.

'Discontented journey'

If the so-called Franco-German motor is still powering the continent (as the prominence of the Merkel-Hollande partnership in everything from the Greek crisis to the Ukraine ceasefire talks suggests), the car is filled with passengers with their own, distinct ideas about which direction to take.

To cope with the large scale arrival of migrants, an external barrier is being built in Hungary, while internal measures have been taken on France's border with Italy. It doesn't look like a roadmap for harmony.

If you rewind to the birth of the EU, the original idea behind it - the European idea, if you like - was a tightly focused one.

By pooling their coal and steel production - and placing those industries under a higher authority - wartime rivals France and West Germany (joined by Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy) would build a foundation for peace.

European Union's ideal

The EU promotes economic and political integration of Europe through:

A common currency

Freedom of movement between member states

Trading market without frontiers

Enlargement

Development of common foreign, security policy

Profile: European Union

They succeeded in preventing wars between EU countries, but, by introducing the idea of a supranational authority, they also sowed the seeds for future disagreements; between those in favour of a federal Europe and those who want to retain the maximum national sovereignty.

Also contained in the 1950 Schuman Declaration, external, the basis for the EU's forerunner, the European Coal And Steel Community, external, was a set of principles from which future members chose to emphasise certain priorities.

As the organisation grew, becoming the European Economic Community (EEC) and then the EU, sovereign countries brought their own perspectives about what membership meant.

Romantic v pedantic

While a country like Britain was attracted to a common market of goods and services, Central and Eastern European nations were most keen on belonging to a unified Europe, no longer separated by an Iron Curtain.

In fact, for the former Warsaw Pact countries, joining the EU was never simply an opportunity to improve their economic prosperity (which it clearly did), or increase their national security (for Eastern Europeans, EU and Nato membership were two sides of the same, post-Soviet coin), but the righting of a historical wrong.

Poland, where I was based in the late 1990s, felt strongly that decades under Communist rule had robbed it of its European destiny.

And that sense of injustice had consequences, as the practicalities of reintegration began. A romantic Europe of memory ran up against a pedantic Europe of rules.

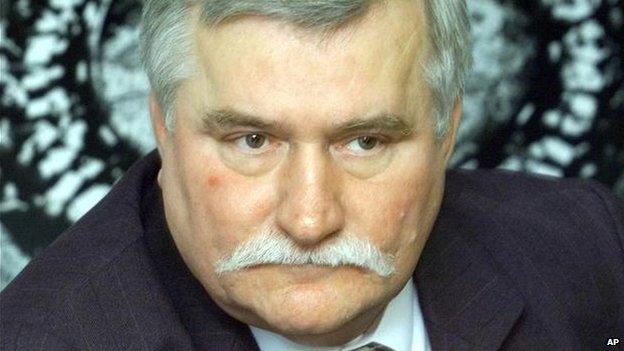

Lech Walesa in 2000

During my time in Warsaw, officials would often express their frustration at the hoops through which their country was being asked to jump.

Specifically, the hoops of the dreaded "acquis communitaire", the long list of EU laws and policies which new members are required to implement.

Bureaucratic wranglings

I remember speaking to former Polish President Lech Walesa in his modest office in Gdansk.

His famous bushy moustache - already grey by then - twitched angrily as he told me that the long, bureaucratic process of accession was an insult to those Polish workers who were the first Europeans on the barricades, in the fight against communism.

To emphasise his point, he gestured through his window at the shipyard, where he made his name as the leader of Solidarity, the Communist Bloc's first independent trade union.

The democracies of Western Europe, he insisted, should be welcoming Poland with open arms, not forcing it to implement standards, which many of them would struggle to meet.

In the end, things worked out well for the Poles. They were among the 10 new members, who officially joined the EU at the beginning of 2004.

Eight countries of central and eastern Europe — the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia — joined the EU, finally ending the post-war division of Europe. Cyprus and Malta also become members in what has been the EU's biggest enlargement

In retrospect, that moment - the EU's single biggest expansion - seems like a political high watermark.

The following year, plans for a constitutional treaty - one of the Federalists' dreams - had to be abandoned, after voters in two original member states - France and the Netherlands - rejected the proposals.

While it's true that many of the ideas reappeared in a reform treaty signed in Lisbon, the public rejection of the EU Constitution exposed the growing scepticism of the governed.

And the new, enlarged Union inevitably brought with it new tensions, in areas such as immigration and jobs.

Southern European countries, whose lower costs and cheaper labour had previously been attractive, found themselves undercut by new members in the east.

How the EU Council works

As businesses moved away, work became more scarce in Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece. Eastern expansion wasn't the only reason for the problems in the European job market, but, a decade later, youth unemployment remains one of the EU's biggest challenges.

One of those playing a key role in meeting those challenges is a former Polish Prime Minister, Donald Tusk, external. Lech Walesa might gain some satisfaction from the fact that a student activist with his Solidarity trade union is now President of the European Council.

Like everyone at the centre of European power, Mr Tusk finds himself in the eye of the Greek storm; struggling to keep the eurozone - and possibly the EU - together. Ironically, his home country hasn't adopted the single currency and seems to have done pretty well without it.

What next?

And here is another historical contradiction; proof, some would argue, of the dishonesty of certain parts of the European project.

At the same time as the EU was insisting that Poland and other prospective members met the exhaustive accession criteria, the founders of the single currency were taking on trust Greece's overly optimistic economic figures and, in some cases (notably, Germany and France) breaking their own, supposedly strict, fiscal rules.

So, one of the key questions now is what kind of European idea will prevail in the Greek negotiations? Will it be a rules-based one or a more pragmatic variation?

The answer has profound consequences for the eurozone, the wider EU - and the countries looking in from the outside.

- Published24 September 2015

- Published16 July 2014

- Published25 February 2014