Harsh Greece deal leaves European vision tainted

- Published

Alexis Tsipras may face a snap election

Athens has been offered a third bail-out. Bankruptcy, the spectre of a failed state, has been avoided, and Greece will stay inside the euro.

But the deal, hammered out over 17 hours, has left many Greeks humiliated.

It is not just the ranks of the left that are using the word "surrender".

Europe has avoided the worst crisis in the EU's history.

"The European project was on a knife edge, external," said one of its leaders. Its reputation, however, has been damaged.

It has shown solidarity with Greece, but divisions have been exposed and it was prepared to see the departure of one of its member states from the single currency.

It struck a deal but only by making Greece accept conditions the majority of Greeks are likely to find unacceptable.

The Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras will return to Greece.

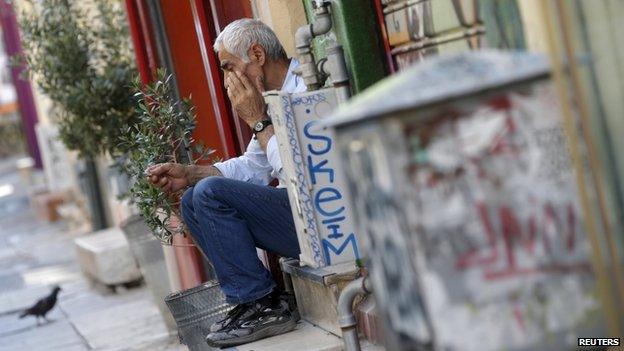

There will be no celebrations, just a weary sigh of relief the uncertainty, for the time being, is over.

Many people were scared Greece outside the euro would descend into bankruptcy and chaos.

Bruising process

Greece, said Mr Tsipras, had fought a tough battle and now faced difficult decisions.

He will have to rush key measures on pension reforms, tax increases and a debt repayment fund through parliament in 48 hours. It will be a bruising process.

European Parliament President Martin Schulz warned the European project was on a knife edge

Only then will bridging loans be released that will enable Greece to meet a payment to the European Central Bank next Monday.

In the election campaign in January, I heard Mr Tsipras tell an ecstatic crowd that tomorrow would mark the beginning of the end of austerity. Tomorrow never came.

Greece remains a laboratory of austerity - with the country back into recession.

The long months of negotiation have ended with Greece's debt on the agenda.

Mr Tsipras said: "We managed to win debt restructuring."

But French President Francois Hollande perhaps put it more accurately when he said: "There will be a profiling of Greek debt by extending the maturities."

Germany has been shown to be unbending - it was prepared to see Greece removed from the single currency.

It clearly did not trust Mr Tsipras and would have preferred to see him out of office and replaced by a technocratic government.

Snap election

It is a lesson for other countries that the eurozone wanted to reshape the Greek government even though it was democratically elected.

As it is, the deal will almost certainly lead to snap elections.

Mr Tsipras will reshuffle his cabinet and discard those cabinet ministers who opposed his latest proposal.

There will be little celebration in Greece

There may not be a national unity government - but he will be dependent on opposition parties who will have an eye on the elections.

Mr Tsipras may win an election, but a portion of the electorate will be unforgiving towards a leader who asked them to vote against more austerity but then signed up for even tougher measures.

Nothing, perhaps, underlined the weakness of his hand as much as when he relented and accepted the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would stay involved in monitoring Greece's actions.

For Europe, the single currency has changed.

It used to be said it was "irreversible". That is no longer the case.

On the table at the summit was a document which contained the words "in case no agreement could be reached, Greece should be offered swift negotiations on a time-out from the euro area, with possible debt restructuring".

European divisions

Economic and monetary union now looks more like a group of countries with a fixed exchange rate system.

The crisis has exposed Europe's divisions. Already, leaders are claiming the Franco-German engine is purring smoothly.

Angela Merkel has taken a hard line

Paris and Berlin ended up on the same side, but there were real tensions.

Chancellor Angela Merkel was furious to discover French technical experts had been advising the Greeks on their final proposal.

Germany was ready to see Greece leave the euro. France was not.

There is now a fault-line in Europe. On one side are Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Slovakia, Belgium, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania.

They were prepared to see Greece leave the euro.

On the other side are France, Italy, Spain and others clinging to their idea of a Europe of solidarity.

For the Germans - whose parliament must meet this week to authorise Mrs Merkel to open talks on a new loan - the union is about sticking to rules and offering help only in exchange for conditions.

Hard road

So will the deal work? If the negotiations succeed, Greece will receive a third bailout and, for a period, it will be off the critical list.

The country is almost certainly back in recession and yet having to accept structural reforms and tax increases - a policy that has failed in the past. Capital controls will stay in place for several months.

Access to money has been tight in Greece

It will be a long, hard road back to growth.

The facts remain. Greece has €320bn in debt. Its debt to gross domestic product ratio is above 180%.

What is missing is the means by which Greece will return to growth.

The deal brings to an end a long period of pretending.

The figures used for Greece to join the single currency were massaged. In 2009, their accounts were proved to be as good as fakes.

Reforms were never fully implemented. Paying taxes was a lifestyle choice.

Many middle-class and wealthy Greeks have their funds in London.

Greece in numbers

€320bn

Greece's debt mountain

€240bn

European bailout

-

177% country's debt-to-GDP ratio

-

25% fall in GDP since 2010

-

26% Greek unemployment rate

The best and the brightest are queuing up to move to Australia and Canada.

As for Europe, it has presided over the economic collapse of a member state. Greece's economy has shrunk 25% in just five years.

The Germans and others will argue they loaned Greece €240bn.

But it was an experiment. Even the IMF conceded it had miscalculated the effects of austerity.

Political union

What will Europe do now? When the dust has settled, it will convince many Europe must move beyond economic and monetary union and embrace fiscal union.

That will require another step towards political union.

Eventually, there will have to be a common treasury and shared debt.

But the Germans will ensure even with deeper integration, the European Union will not become a transfer union with funds flowing from north to south.

With the Greek crisis, the European project has lost some of its vision, its idealism, its hope.

It is a project in need of revival.