How bad are things for the people of Greece?

- Published

The people of Greece are facing further years of economic hardship following a Eurozone agreement over the terms of a third bailout.

The deal included more tax rises and spending cuts, despite the Syriza government coming to power promising to end what it described as the "humiliation and pain" of austerity.

With the country having already endured years of economic contraction since the global downturn, just how does Greece's ordeal compare with other recessions and how have the lives of the country's people been affected?

The long recession

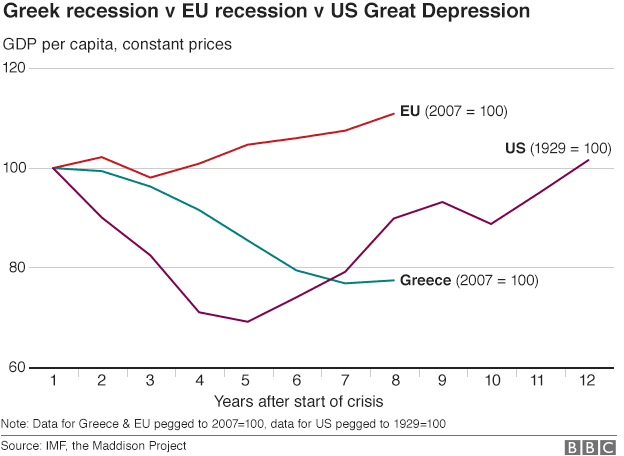

It is now generally agreed that Greece has experienced an economic crisis on the scale of the US Great Depression of the 1930s.

According to the Greek government's own figures, the economy first contracted in the final quarter of 2008 and - apart from some weak growth in 2014 - has been shrinking ever since, external. The recession has cut the size of the Greek economy by around a quarter, the largest contraction of an advanced economy since the 1950s.

Although the Greek recession has not been quite as deep as the Great Depression from peak to trough, it has gone on longer and many observers now believe Greek GDP will drop further in 2015.

Dwindling jobs

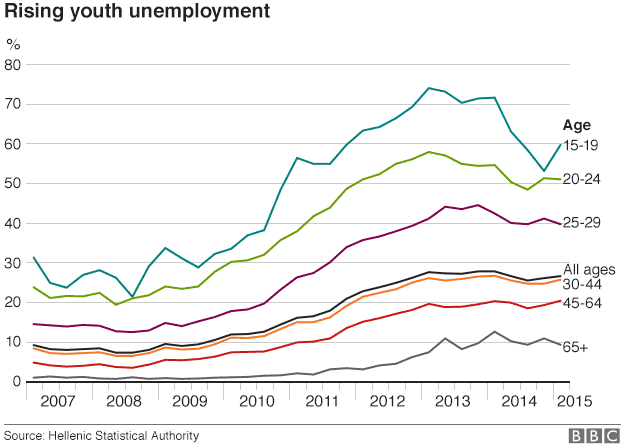

Jobs are increasingly difficult to come by in Greece - especially for the young. While a quarter of the population are out of work, youth unemployment is running much higher.

Half of those under 25 are out of work. In some regions of western Greece, the youth unemployment rate is well above 60%.

To make matters worse, long-term unemployment is at particularly high levels in Greece.

Being out of work for significant periods of time has severe consequences, according to a report by the European Parliament., external The longer a person is unemployed, the less employable they become. Re-entering the workforce also becomes more difficult and more expensive.

Young people have been particularly affected by long-term unemployment: one out of three has been jobless for more than a year.

After two years out of work, the unemployed also lose their health insurance.

This persistent unemployment also means pension funds receive fewer contributions from the working population. As more Greeks are without jobs, more pensioners are having to sustain families on a reduced income.

According to the latest figures from the Greek government, 45% of pensioners receive monthly payments below the poverty line of €665.

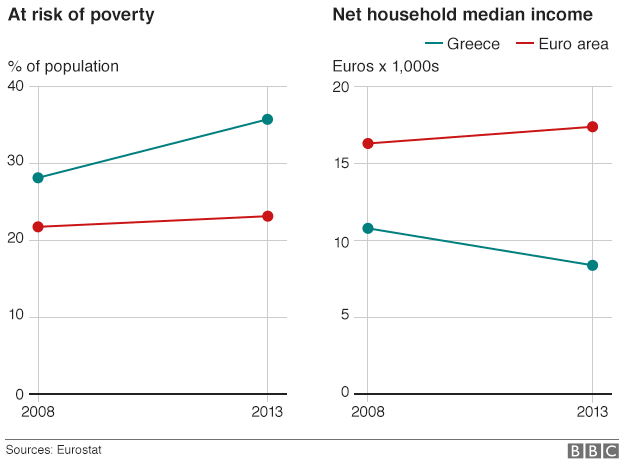

Plummeting income

The Greek people are also facing dropping wages.

In the five years from 2008 to 2013, Greeks became on average 40% poorer, according to data, external from the country's statistical agency analysed by Reuters. As well as job losses and wage cuts, the decline can also be explained by steep cuts in workers' compensation and social benefits.

In 2014, disposable household income in Greece sunk to below 2003 levels.

Rising poverty

Like during all recessions, the poor and vulnerable have been hardest hit.

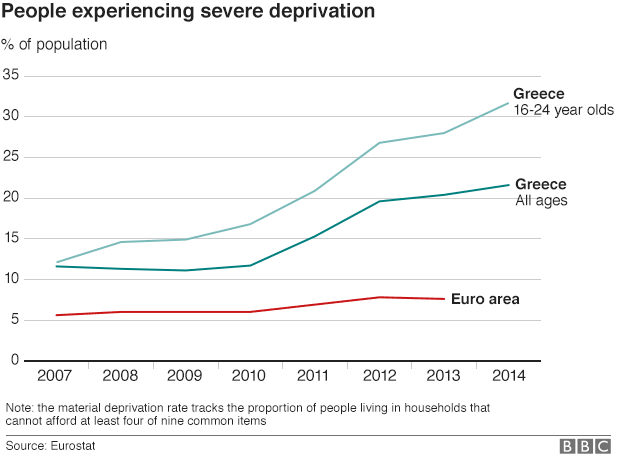

One in five Greeks are experiencing severe material deprivation, a figure that has nearly doubled since 2008.

Almost four million people living in Greece, more than a third of the country's total population, were classed as being 'at risk of poverty or social exclusion' in 2014, external.

According to Dr Panos Tsakloglou, economist and professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business, the crisis has exposed Greece's lack of social safety nets.

"The welfare state in Greece has historically been very weak, driven primarily by clientelistic calculations rather than an assessment of needs. In the past this was not really urgent because there were rarely any particularly explosive social conditions. The family was substituting the welfare state," he told the BBC.

Typically, if a young person lost his or her job or could not find a job after graduating, they would receive support from the family until their situation improved.

But as more and more people have become jobless and with pensions slashed as part of the austerity imposed on Greece from its creditors, ordinary Greeks are feeling the impact.

"This has led to many more unemployed people falling into poverty much faster," Dr Tsakloglou said.

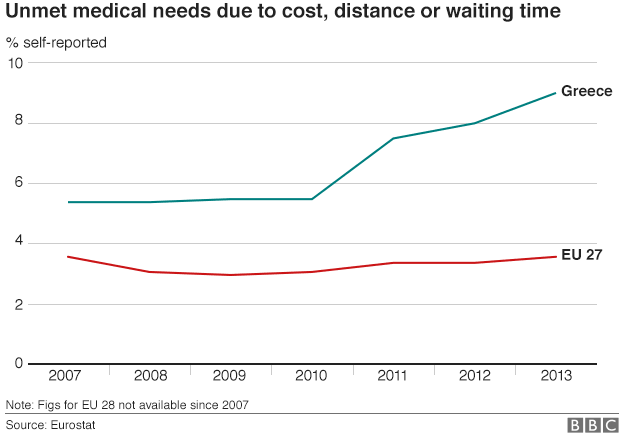

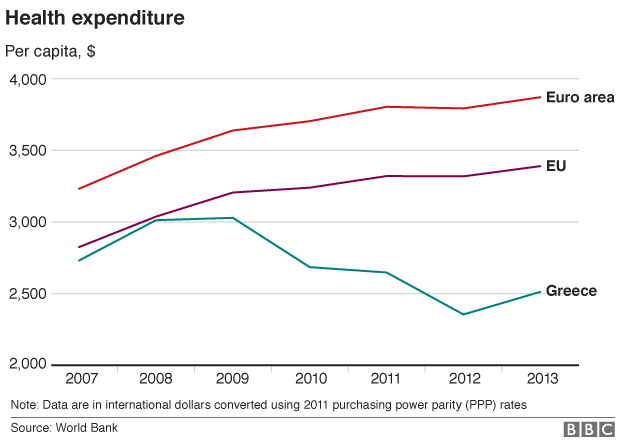

Cuts to essential services

Healthcare is one of the public services that has been hit hardest by the crisis. An estimated 800,000 Greeks are without medical access due to a lack of insurance or poverty.

A 2014 report , externalin the Lancet medical journal highlighted the devastating social and health consequences of the financial crisis and resulting austerity on the country's population.

At a time of heightened demand, the report said, "the scale and speed of imposed change have constrained the capacity of the public health system to respond to the needs of the population".

While a number of social initiatives and volunteer-led health clinics have emerged to ease the burden, many drug prevention and treatment centres and psychiatric clinics have been forced to close due to budget cuts.

HIV infections among injecting drug users rose from 15 in 2009 to 484 people in 2012.

Mental wellbeing

The crisis also appears to have taken its toll on people's wellbeing.

Figures suggest that the prevalence of major depression almost trebled from 3% to 8% of the population in the three years to 2011, during the onset of the crisis.

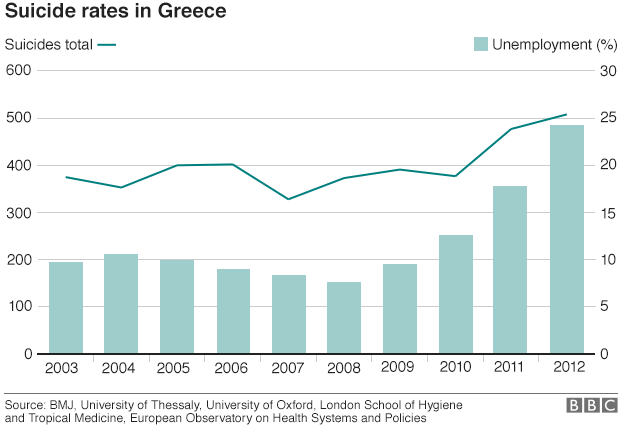

While starting from a low initial figure, the suicide rate rose by 35% in Greece between 2010 and 2012, according to a study published in the British Medical Journal., external

Researchers concluded that suicides among those of working age coincided with austerity measures.

Greece's public and non-profit mental health service providers have been forced to scale back operations, shut down, or reduce staff, while plans for development of child psychiatric services have been abandoned.

Funding for mental health decreased by 20% between 2010 and 2011, and by a further 55% the following year.

The brain drain

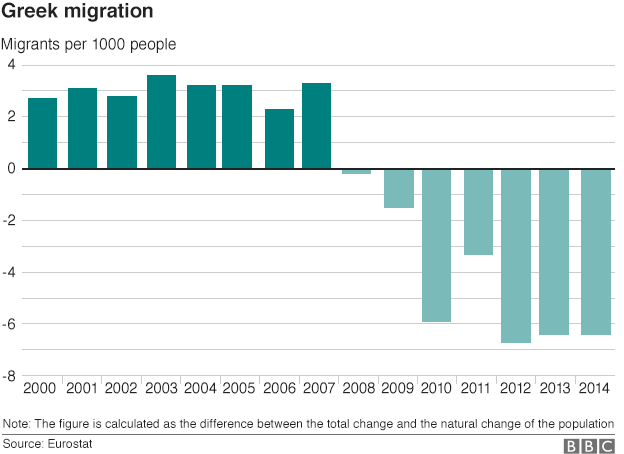

Faced with the prospect of dwindling incomes or unemployment, many Greeks have been forced to look for work elsewhere. In the last five years, Greece's population has declined, falling by about 400,000.

A 2013 study, external found that more than 120,000 professionals, including doctors, engineers and scientists, had left Greece since the start of the crisis in 2010.

A more recent European University Institute survey, external found that of those who emigrated, nine in 10 hold a university degree and more than 60% of those have a master's degree, while 11% hold a PhD.

Foteini Ploumbi was in her early thirties when she lost her job as a warehouse supervisor in Athens after the owner could no longer afford to pay his staff.

After a year looking for a new job in Greece, she moved to the UK in 2013 and immediately found work as a business analyst in London.

"I had no choice but leave if I wanted to work, I had no prospect of employment in Greece. I would love to go back, my whole life is back there. But logic stops me from returning at the moment," she said.

"In the UK, I can get by - I can't even do that in Greece."

- Published14 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published10 July 2015