German muscle threatens European solidarity

- Published

Greece feels it has been harshly treated

This is not the end of the drama for the European Union. Perhaps, the passion play we are witnessing is just the prologue to tragedy.

Tragedy, after all, depends upon the blossoming of flaws that undermine an otherwise noble character.

In this case, it makes the Europe Union wrestle with the central conundrum behind its existence.

The European dream was conjured out of a nightmare - it was, in origin, a project to exorcise the family ghost: the vast power of one country, Germany.

There are many other, more obvious, flaws to be examined.

With Greece treated not far short of a satrapy of permanent recession, the climax to the crisis raises one of the most serious charges against the European Union - that it overrides national democracy.

That the International Monetary Fund (IMF) regards the plan as all but pointless, external adds to the angst.

Germany's interests are central to the other big question - if the euro is not fit for purpose, external, what new rules could make it function better?

For this and other reasons, this is a pivotal point for modern Germany.

Search for stability

So, a bit of history.

In the common imagination, at least on the Continent, if not in the UK, the European project is about "peace".

In the aftermath of the World War Two, the driving impetus was how to avoid Europe ever going to war again.

That is putting it politely -it was how stop Germany ever again doing violence to a continent.

Germany now has a powerful military

Behind this simple desire was a much more difficult and complex problem.

How to have stability on a continent where one nation had the potential to dominate - economically, politically, and militarily.

Dismember and demilitarise Germany was one solution. That has long gone: there is now a united Germany with a powerful if a rather under-resourced Bundeswehr, external.

The other solution was called the European Coal and Steel Community.

It is still very much with us, in the shape of the EU.

The ECSC put the materials of war under supranational control, external, incidentally creating a common market into the bargain.

The prosaic details of the evolution of the common market, and the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Community (EC) and then the EU disguise a vast intellectual leap, one never taken before by any country.

Chancellor Konrad Adenauer signed the Treaty of Paris

European Coal and Steel Community:

proposed by French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman on 9 May 1950, as a way to prevent war between France and Germany

formally established in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris as the first international organisation to be based on the principles of supranationalism

created a common market for coal and steel among member states

founder members were Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Luxembourg

Merged with other similar subsequent organisations to form the European Economic Community in 1967, a precursor to the European Community

In its post-War guilt, Germany accepted it would put the interest of peace and harmony in Europe before its national interest, that its selfish and strategic interests, to coin a phrase, were to be subordinated to the needs of Europe as a whole.

This was never stated of course, never in any treaty but it was understood, particularly by the Germans themselves.

European solidarity is now as much a part of the German soul as blood and iron ever were.

But no-one should expect Germany to forever jump at its own shadow, remain ever subject to the fear of ghosts.

Over the past few years, Germany has been coming out of its shell, cautiously enthusiastic about exercising more power on the world stage.

But when I was looking at this in Berlin at end of last year, two things became very clear.

When it comes to diplomatic or military clout, the exercise of greater power would be done in a European context.

The second thing was the fear of a reaction.

When I asked: "Why not do more?" policymakers raised the reaction of Greece to imposed austerity - cartoons of Chancellor Angela Merkel as Hitler, the swastika there in the background in street demonstrations.

Perception of bullying

Germany is far more confident about using economic clout than diplomatic or military influence. Nevertheless, it has a deep aversion to being seen as a hectoring bully.

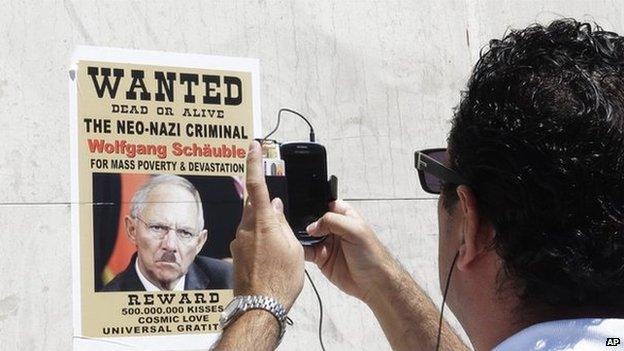

Which is why it is almost incredible that the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, external has single-handedly resurrected a perception, external of his country that was deservedly buried long ago - the promoters of a brutal, remorseless, logic riding roughshod over compassion.

After the bailout summit, a Schaeuble "Wanted" poster appeared in Athens

It is certainly ridiculous to make comparisons with a dark past, external. But it is pretty clear that many Greeks see Germany as the author of their misfortunes and will still hark back to an era long gone.

Both the solutions on the table last weekend, Greek exit or the current deal, were German creations.

Recently resigned Greece Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, while not a neutral observer by any means, is probably right that German attitudes "completely and utterly" control the Eurogroup, external.

He said of Mr Schaeuble: "It is all like a very well-tuned orchestra, and he is the director."

It is this growing German ambivalence between the national and European interest that makes this moment so pivotal.

It is fair enough to point out that other smaller countries almost certainly sheltered behind Germany, happy not to be in the spotlight.

And some think when it really mattered the old stuttering Franco-German engine roared into life at the very last moment to secure a deal.

You can also argue that this was a French victory, because the Germans perhaps chose their second option - possibly against their own interests but perceived as less damaging to Europe as a whole.

But they still got their way.

The German insistence on the cloak of the spirit of solidarity is why Mrs Merkel's Chief of Staff, Peter Altmaier, tweeted ever so humbly, ever so modestly that the deal was good for the collective.

"Europe has won," he wrote. "Commanding and strong. Germany was part of the solution - from the start to the finish."

Angela Merkel and Peter Altmaier are keen to promote an image of European solidarity

Germany was also part of the problem, from the start to the finish.

But the real point is, after a lot of bluster, Germany's leaders once again put what they saw as the needs of European unity before a policy that might be more pleasing to the German people, external and parliament.

Fat lot of good that will do them.

The imposition of what looks suspiciously more like punishment than fiscal common sense does look a lot like Germany - and its allies - imposing their will on another country.

Germany has decided, for the moment, that it wants the eurozone to remain intact.

If this holds, it will inevitably lead to calls for closer political union to manage the currency in lines with German interests - the former Belgium Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt has told me the 19 countries need a single treasury and central taxation otherwise they might as well abandon the euro.

There is a logic here - but it pulls counter to the mood of the times.

As memories of Europe's terrible past fade and Germany hesitates to shoulder the burden of a continent for evermore, "solidarity" may become and increasing rare and precious resource.