How a UN intern was forced to live in a tent in Geneva

- Published

David Hyde said life in Geneva was "way more expensive than I imagined"

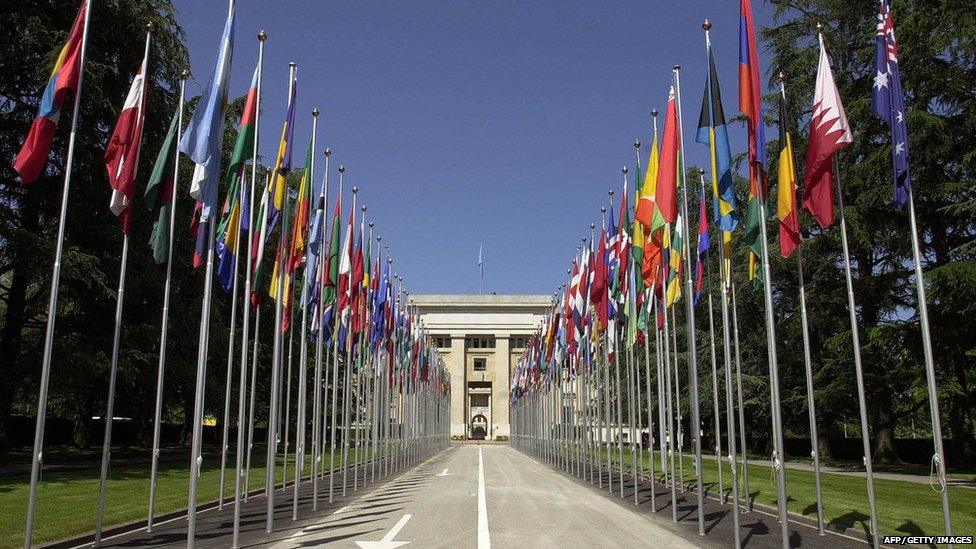

The case of a United Nations intern found sleeping in a tent on the shores of Lake Geneva has drawn attention to the United Nations practice (one it shares with big business and some European Union institutions) of employing interns on an unpaid basis.

David Hyde, a 22-year-old from New Zealand, was delighted when he was accepted as an intern with a UN agency. He had hoped for a paid position, because, he says: "I think my work does have a value."

But he was happy to take the UN offer because of the prestige attached to working for such a renowned organisation.

He admits that, during the interview process, the UN told him quite clearly that Geneva was an expensive town, and wanted reassurances that he would be able to fund his internship himself.

"I guess my budget was not realistic in the end," he says. "It was way more expensive than I imagined. I thought I could find a really budget way to live, but to be honest I've ended up living in a tent."

He is, he says, not keen to be seen as a victim, and points out that camping on the shores of Lake Geneva during the summer months is not actually "all that bad".

He had not spent too many nights there before he was noticed, and soon his story was on the front pages of the Geneva newspapers.

Genevans were shocked that the famous and much-loved institution should be connected to such a case.

But inside the United Nations itself, there was little astonishment.

"It doesn't surprise me at all," says Sabine Matsheka from Botswana. Sabine is chair of the Geneva Interns Association. "We get desperate calls and emails from interns asking for couches, air mattresses, just a place to stay."

Sabine, who is interning with the United Nations Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), says she too has had difficulty making ends meet.

"The unpaid element has influenced my internship," she says.

"I had to plan very carefully with my funds and that's why I had to stick to three months because that is what I could be supported by my family and my own funds.

"I wish I could stay longer."

UN officials have been taken aback by the huge attention now being paid to David's case.

"Interns get a lot of experience," says Ahmad Fawzi, head of the UN's information service in Geneva. "First-hand knowledge about how the international system works: it's invaluable for them, and they have fun."

Mr Fawzi also points out that the policy of not paying interns comes not from the UN agencies themselves, but from the UN General Assembly which, some years ago, passed a resolution allowing the recruitment of interns, but prohibiting their payment.

And, he insists, the UN does its best to offer a few perks, negotiating cheaper rates for interns on Geneva's public transport system, and offering discounts at the UN cafeteria.

Those, however, will hardly compensate for the sky-high rents which confronted David when he arrived.

"I feel this young man may not have done his research," says Mr Fawzi.

Sleeping in the basement

Unpaid internships are commonplace these days, and they can be good experience for young people hoping to gain experience in a possible future career field.

But Ian Richards, who heads the UN staff trade union in Geneva, believes the United Nations is the one organisation that should not be using unpaid labour, however valuable the experience.

"It does make this organisation look terrible," he says.

"Here's the United Nations, it's supposed to set the standards when it comes to labour standards, reaching out to the young, reaching out to people in developing countries, and it doesn't seem to be able to do that."

What's more, he points out, UN agencies employing unpaid interns are in danger of violating the very principles, such as the abolition of slave labour, which they exist to promote.

"A few years ago at the International Labour Organisation, they found an intern sleeping in the basement," he remembers.

"That created a lot of noise in the press and, as a result, the ILO decided to pay its interns."

Meanwhile Sabine Matsheka points that continuing with the policy of unpaid interns simply ensures that only candidates with personal funds can apply. At the moment, of the 34 interns in Sabine's section alone, she is one of just two from Africa.

"I am from a developing country," says Sabine, "and I know of many people from my university who would have loved this opportunity but could probably not afford to do it."

But if the ILO can find a way to get around General Assembly rules and pay its interns, surely other UN agencies can do the same?

As ever with UN bureaucracy, it is not quite as simple as that.

All agencies attached to the UN Secretariat, among them OCHA, UN Human Rights, and the UN Conference on Trade and Development, remain bound by that old General Assembly vote forbidding the payment of interns.

"I personally, everyone here agrees," says Ahmed Fawzi. "They should be paid.

"But the only way to change it is for a member state to draft a resolution and submit it to the General Assembly and put it to the vote. I have no doubts it would be accepted immediately.

"It's not up to us, the civil servants, it's up to member states to change the rules."

Drafting, adopting and introducing UN policy can, as with any legislative body, take years. So any change will not affect today's interns, and certainly not David, who is now rolling up his tent.

The expense of Geneva, the unpaid status, and now the pressure of media attention have all been too much and he has decided to resign, although he is keen to stress that his UN colleagues in Geneva are not to blame.

"The United Nations has done nothing to try to stop me talking about this subject," he says.

"They have been nothing but supportive, they don't want to see me in this situation. But on a structural level, there is a kind of missing link in terms of support.

"I'm not sure what I'll do moving forward."