Migrant crisis: The volunteers stepping in to help

- Published

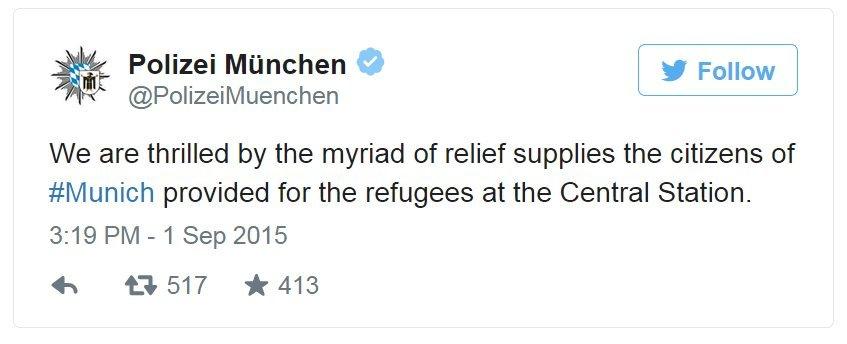

Volunteers are giving their time to sort food donations for refugees at Munich's Central Station

George Chertofilis was an ordinary physics teacher looking forward to a long summer holiday when the dinghies began to arrive, one after another, on the Greek island of Kos. Before long, hundreds of migrants were landing on the island every day.

In sight of Turkey's coast, Kos has become one of the first ports of call for the mainly Syrian and Afghan migrants fleeing through Turkey to Europe. A member of the coastguard told the BBC that 750 people arrived on the island in the first few hours of daylight on Thursday morning alone.

Aid workers estimate that there are about 7,000 migrants on the island - which ordinarily has just 30,000 citizens. And with no support forthcoming from local authorities, it is the island's citizens who have stepped in to help those arriving by sea.

"We have no choice," says Mr Chertofilis. "People are starving, we cannot leave them like this. We cannot do that."

So the physics teacher's summer holiday has been spent fundraising, cooking, and distributing food and clothes to the thousands of desperate people arriving on the island. His Kos Solidarity Project now has 50 volunteers and collects donations from many more.

Led by Mr Chertofilis, ordinary men and women on Kos are working for hours before and after their day jobs, often from the break of dawn until late into the night, in an attempt to stem the humanitarian disaster unfolding on their doorsteps.

Thousands of migrants have landed on Kos after fleeing Syria and Afghanistan via Turkey

Mr Chertofilis works for about nine hours every day after he finishes teaching.

"We have to help them," he says. "They don't have clothes, they don't have shoes, they don't have food. If we don't help them, what will happen?"

Kos residents have allowed migrants into their courtyards to sleep and into their homes to wash, he says. Many have donated food, clothes, and medicines and bought items to order on their weekly food shops.

Taking the initiative

The people of Kos are not alone - stories are emerging of citizens around Europe taking the initiative to help.

Diana Henniges is a social worker in Berlin who could see first hand that not enough was being done to help, so she offered her time. She is working for a volunteer group called Moabit Hilft, answering the phone to people across the city who want to help.

"People are calling from all over the city to help, to offer money, clothes and food," she says. They are also offering their homes - five people called in the first 15 minutes of Ms Henniges's shift on Thursday to say they will take someone in.

"The refugees here need food, they need money and they need places to stay overnight," she says. "The people are trying to help where the state can't manage."

An apple is handed out by a volunteer in Berlin

Germany is the main destination for migrants arriving on the EU's eastern borders and German authorities say they are expecting about 800,000 asylum seekers in 2015, four times the number last year. The country has not committed to accepting a specific number, but has said it will no longer return Syrians to their first port of entry in the EU.

Elsewhere in Berlin, a couple say they have been overwhelmed with offers after creating a website called Refugees Welcome, external, to match migrants and refugees with people willing to take them in.

Described as an "Airbnb for refugees", the initiative has helped find homes for people fleeing Afghanistan, Liberia, Mali, Iraq, Somalia, Syria and many other countries.

The site's two founders, Jonas Kakoschke, 31, and Mareike Geiling, 28, have taken in Bakari, a 39-year-old refugee from Mali, and they say a further 122 migrants have already found homes across Germany though their initiative.

In Munich, volunteers have gathered at the city's Central Station to meet migrants with cheers of welcome and supplies of bottled water, bread, nappies, fruit and sweets. Banners were displayed with messages of welcome, echoing those held aloft at football matches across Germany last weekend.

Hundreds of people in Munich have come every day to the station to offer their time, said Colin, a volunteer coordinator. So much was donated that police politely asked the volunteers to stop for the day.

And the desire to help stretches beyond Germany. In the Spanish cities of Madrid and Barcelona, so many families offered to help that city authorities are creating an official register to match them with migrants.

In the French port city of Calais, people have donated books and food and a family took in a 20-year-old Syrian boy who knocked on their door asking for water.

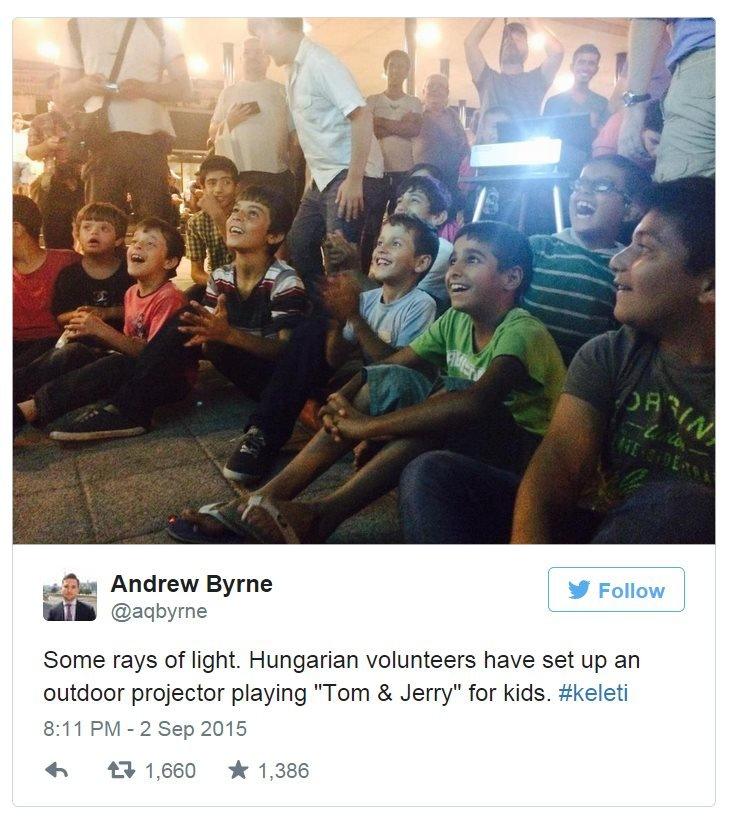

In Hungary, where migrants were last week sprayed with tear gas by police, some locals set up a projector to screen Tom and Jerry for the children. An image of the boys, laughing brightly at the cartoon, was shared widely on Twitter on the same day a young Syrian boy drowned trying to make it to Kos.

Citizen to citizen

As the image of that young Syrian boy appeared on the front pages of all the UK papers, Elinor Mountain, from Kilkenny in the Republic of Ireland, arrived on Kos.

She and her husband had already booked a holiday to the island when the images of its migrant influx hit the news. The Mountains starting raising money in Kilkenny with events and collections.

"There was a huge desire to help," she says. "Somebody I just met at the leisure centre gave me a cheque for €250 (£180; $280)." The couple flew to Kos with €2,200 to give to the island's volunteer groups, including Kos Solidarity.

"People are feeling helpless and they want to do something," says Ms Mountain. "They want to take action, citizen to citizen. They want to change the debate from one about fear to one about human beings helping human beings."

The cash Ms Mountain took with her will be spent on tents, food and soap. The volunteers on Kos are a lifeline for refugees, she says. "There is a sense of humanity, people reaching out to these refugees with support."

But ultimately, volunteers are not a solution to the problem, says Ms Henniges in Berlin. "The local authorities need to do more," she says. "There is so much more they could do, and they should but they don't. And volunteers are having to fill the gap."

And from where George Chertofilis is standing, these individual stories, though heartwarming, simply don't match the scale of the crisis unfolding across the continent. "There are just too many people," he says.

More than 350,000 migrants are known to have entered the EU between January and August 2015, compared with 280,000 for the whole of 2014. And that figure - an estimate from the International Organization for Migration - does not include the many who entered undetected.

"We have solidarity but we are not the answer," says Mr Chertofilis. "We have not had any help from the authorities, not the municipality or the government. The mayor of Kos says the people will help the refugees."

No one from the mayor's office was available to talk to the BBC, and Mr Chertofilis says he has had no response to his own inquiries for weeks.

"The Greek authorities have to provide a solution," he says. "The European Union has to provide a solution. We are waiting until this day."

But how long can you wait, I ask. "I don't know, I don't know," he says. "We will keep trying until the end."

- Published31 May 2015

- Published16 June 2015

- Published8 June 2015