Greece crisis: Cancer patients suffer as health system fails

- Published

After arriving at the Theageneio specialist cancer hospital in Thessaloniki, Betty Semakoula was distraught to learn that her CAT scan was not going to happen that day.

"The machine is not working," hospital staff told her.

"You should come back in four months."

But Betty did not have that long.

"I had no choice but to get a private screening," she said. "I paid €600 (£390) out of my own pocket."

The 35-year-old, who founded an NGO that helps poor and homeless people in Thessaloniki, says her experiences suggest Greece's health system is increasing comparable to those she witnessed while working in the developing world - rather than that of an EU country.

And from speaking to other patients and healthcare workers here, it is clear her story is broadly typical.

Betty Semakoula has struggled to get the care she needs

As Greece careers towards another election later this month, the country's healthcare system is continuing to crumble.

Funding for state-run hospitals has been cut by more than 50% since the debt crisis started in 2009.

They suffer from severe shortages in everything, from sheets, gauzes and syringes, to doctors and nurses.

By 2011, supplies were critically low, says Athena, a former nurse in a haematology unit.

"We did not even have the most basic of materials [such as] surgical spirit."

Public health spending in Greece is expected to shrink to 4% of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of 2015, one of the worst levels in the EU. The average spend is 6.9%, according to the Panhellenic Medical Association.

The National Organisation for Healthcare (EOPYY) is running a deficit of €1.5bn. Allocated hospital funding, which has slowed to a crawl since March, will fall this year by more than 22% to €1.18bn.

A new bailout agreed with Greece's creditors by the former coalition government headed by the left-wing Syriza party will do little to address the situation, experts say, as it dictates a prolongation of austerity and spending cuts.

'Go private'

Greeks who have the financial means are increasingly turning to the private sector.

A 77-year old woman, named Nikki, recently suffered a stroke at 03:00 in the morning.

The paramedics who arrived at her house in Kalamaria, an affluent Thessaloniki suburb, told her panicking son that his mother should be seen by a doctor as soon as possible.

But they warned him not to take her to the local public hospital that night.

"The hospital is overcrowded. It may take hours for her to see a doctor. You'd better get her to a private clinic," they said.

Elderly patients are often hit hardest by the funding crisis

The son immediately drove his mother to the nearest clinic.

There were no queues, but rather an abundance of medical staff to help her.

But all this came at a price. She paid €800 for her screening and three-day hospitalisation.

Not everyone is so lucky. Most Greeks, even those who have jobs, cannot afford private healthcare.

The situation is even worse for the estimated 2.5 million uninsured Greeks.

Having lost their jobs and health coverage, getting access to healthcare is a huge challenge.

Syriza acknowledges as much. The party's manifesto unveiled ahead of the 20 September election warns that the health crisis hurts primarily the country's poor and vulnerable.

Massive understaffing

Few patients blame the medical staff - they know they are overworked and underpaid.

"We are short on doctors and nurses. We work almost non-stop to provide for them as best we can," says Athina Grammatikopoulou, a nurse at Theageneio hospital where Ms Semakoula was turned away.

"For example a single nurse has to care for 20 or 25 patients during night shifts."

Greece healthcare crisis

Decline in government spending

10%

of GDP went on healthcare in 2009

4%

of GDP is the expected spend for 2015

-

22% decline in allocated hospital funding in 2015

-

5,000 more doctors needed

-

15,000 more nurses needed

According to the government, the system requires 4,500 extra doctors and other medical and paramedical staff.

But Michael Vlastarakos, President of the Panhellenic Medical Association, says the Greek healthcare system is 5,000 doctors and 15,000 nurses short.

The understaffing is getting worse because of a mass exodus of doctors and nurses, who have seen their salaries cut and work hours increase.

"In the past three years, more than 15,000 doctors have left the country, mainly for the UK, Germany, Cyprus and Sweden," says Mr Vlastarakos.

"The dramatic understaffing means, for example, that in Sparta, my hometown, the pathology clinic is no longer operating."

Bribes

Doctors working at public hospitals in Greece earn on average about €1,200 to €2,000 a month - and payments are often seriously delayed.

Mr Vlastarakos says low pay is one reason why the problem of the infamous "fakelaki", or illegal bribes, is still rife.

"A patient who is told that he can only be operated in three months' time has two options: go to a private clinic or pay his way up the waiting list," he says.

Cancer patients are particularly vulnerable.

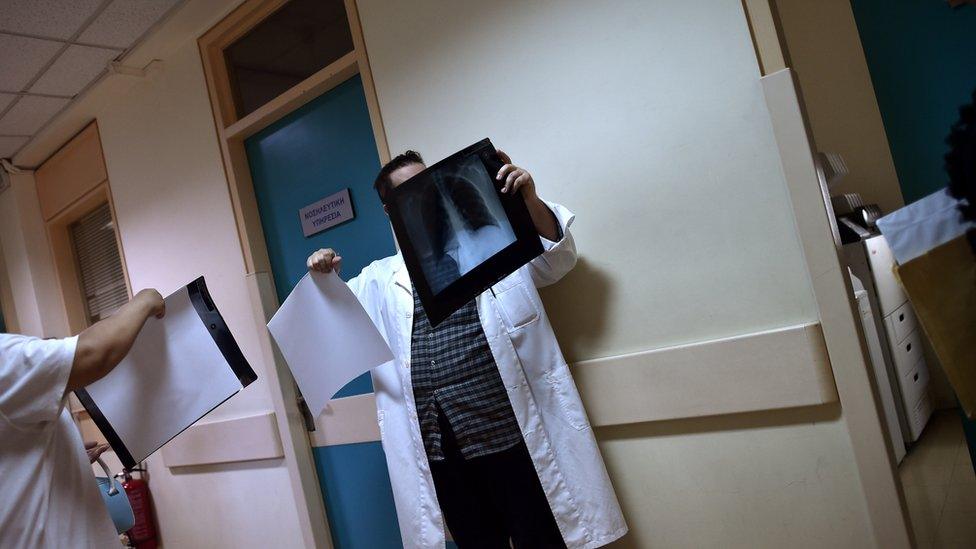

Many doctors and nurses have left the country leaving Greek hospitals badly understaffed

Persefoni Mitta, head of the Association of Cancer Patients in Macedonia and Thrace, spends her days trying to help the 6,500 members of her organisation in their fight against the disease.

"Some are sent away from the hospitals because the machine may not be working, or chemotherapy is impossible," she says.

"Others come crying because they were discharged from the hospital right after an operation."

Spitting mad

What they all have in common is their outrage towards politicians.

"They spit at politicians. And rightfully so. They should be ashamed of themselves," says Ms Mitta.

"The only thing they know how to do is hold new elections every couple of months, while people out there are suffering".

Persefoni Mitta was diagnosed with multiple forms of cancer herself and now helps other access the right care

Another problem is drug shortages. Commercial pharmacies are owed more than €0.5bn by the government, according to the Panhellenic Pharmaceutical Association (PFS), so many request payment from patients up front.

Iosif Vaena, a pharmacist in Thessaloniki, says shortages are real, with some drugs including insulin running low, and others becoming simply unavailable, like the polio vaccine.

And even in the case of medicines that are theoretically available, patients need to pay out of their own pocket to get them.

'Give up'

Then there are medicines that are essential but so cheap that no company will import them. These are covered by emergency imports, but the government agency responsible has no funds to pay for them and has stopped placing orders.

Cancer drugs are vital, but often inaccessible.

"It is one thing to ask a patient to bring his own blanket to the hospital. And quite another to deny him a drug that means the difference between life and death," Ms Mitta says.

Sometimes doctors tell cancer patients to give up, she adds.

"A doctor will say, 'He is 70 years old, there is no point in spending money and resources on him'. But who are they to decide?"

She says she faced the same attitude when she was diagnosed with multiple forms of cancer 28 years ago.

"They said I only had three months to live... But here I am, still breathing."