Migrant crisis: Hungary crossings echo 1989 and 1956

- Published

In 1989 it was East Germans pouring across the Hungarian border into Austria

The BBC's Nick Thorpe on the Hungarian border compares the huge movement of people 25 years ago, when thousands of East German refugees were allowed into Austria, with the mass migration of today.

The logo on the side of the locomotive of the 0905 Budapest to Munich Intercity train could not have been more ironic: "Pan-European Picnic - 25 years of Open Borders."

The Pan-European Picnic was the remarkable event on the Hungarian-Austrian border in August 1989, when the border guards of Communist Hungary defied orders and stood aside and allowed hundreds of East German refugees to run across the border into Austria.

The green carriages of the train to Munich on Thursday morning soon filled with Syrians, Afghans, Iraqis and a host of other nationalities.

Thousands of East Germans streamed across the border after Hungarian authorities lifted travel restrictions in 1989

Hungarian government officials insist that there is no parallel between 1989 and 2015

Many Hungarians have personal memories of having to run for their lives

They were trapped in Hungary by the decision of the Hungarian government to block their route to Germany.

But the train did not go to Munich. The gates of the station had opened at 08:20, closely followed by a stampede of refugees.

At 08:52 the government spokesman, Zoltan Kovacs, informed me that the refugees would be taken to refugee camps instead.

At 11:00 the train left, and at 12:00 it arrived in Bicske, the site of a refugee camp, 37km (23 miles) west of Budapest. The refugees refused to leave, and a 28-hour standoff with police developed.

Razor wire fence

I spoke to local people, who wandered down to the tracks to see world news unfolding on their doorstep.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has warned that millions, not hundreds of thousands of migrants will flood Europe

When people see the refugees in Hungary today, they are torn between an official rhetoric which often demonises "illegal migrants", and their own experience of expulsion and charity

Many Hungarians, especially those fed a diet of anti-migrant vitriol on state radio and television, are suspicious of the thousands of people from other cultures now traipsing through their country.

So I was surprised when one woman said quietly to me: "You should remember that many of us, Hungarians, were refugees too".

She belonged to the Hungarian minority in Romania, and fled to the country in the 1980s, to escape the terrifying regime of Nicolae Ceausescu, she said.

Hungarian government officials insist that there is no parallel between 1989 and 2015.

Or between the Iron Curtain which once split Europe, and the razor wire fence they are still reinforcing along their southern border with Serbia.

Or between the 1956 revolution, when a quarter of a million Hungarians escaped across the same border into Austria, to escape Soviet tanks, and current events.

But the fact is that many Hungarians, Slovaks, Czechs, Poles, Serbs and Romanians, not to mention Germans and Austrians, have personal memories of having to run for their lives.

Some remember those stories from their parents and grandparents. And when they see the refugees in Hungary today, they are torn between an official rhetoric which often demonises "illegal migrants", and their own experience of expulsion and charity.

One big difference between 1956, 1989, and 2015 is cultural. Many of the new arrivals are Muslims. Some are Africans. These are not Europeans fleeing within Europe.

Walk the streets of Budapest, Prague or Bratislava, and the faces are more homogenous.

Only the Chinese and Vietnamese are here already in large numbers.

This is largely the result of the mass murders and forced population movements of the Second World War and its immediate aftermath.

'Defending Christian Europe'

Another problem is a genuine resentment in eastern Europe at being talked down to by west European leaders.

For the Hungarians, the sheer numbers now are also an important factor.

By Saturday night, 175,000 asylum seekers had been registered by the Hungarian authorities this year - 50,000 in August alone.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has warned that millions, not hundreds of thousands of migrants will flood Europe.

Nobody knows if that is true, not even Mr Orban, but only one year ago two million Hungarians trusted his word enough to vote him into office for four more years.

There is also now a sort of rearguard action by the governments of Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic to defend what they regard as "Christian Europe" from those it regards as "aliens".

Robert Fico's Slovak government only reluctantly agreed to accept 200 asylum seekers from Syria, awaiting processing in neighbouring Austria, on condition that they are Christian.

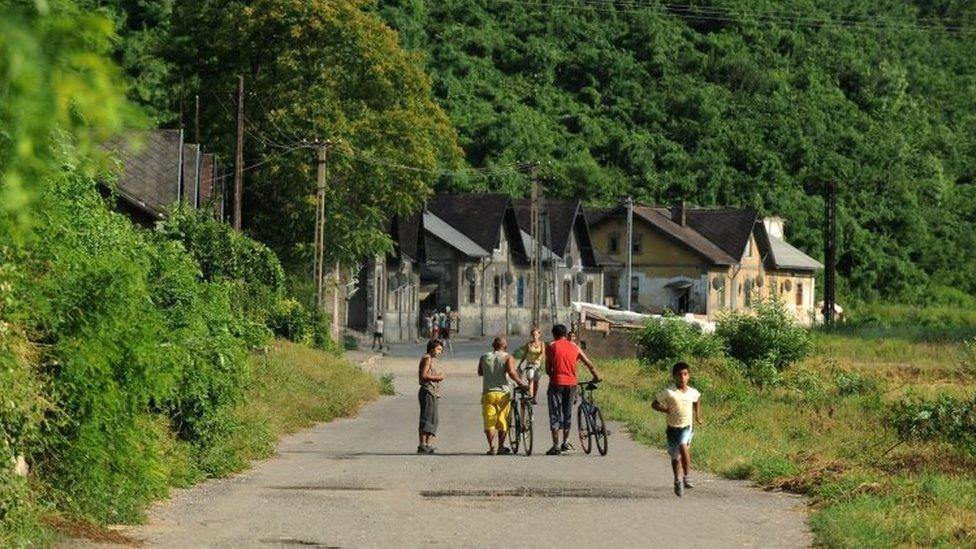

Yet another factor in the migration equation is the large ethnic Roma population in eastern Europe.

Hungarian ministers argue that they cannot cope with an influx of refugees when it already has 800,000 Roma to integrate

The mass migration of people out of and into Hungary is not unprecedented

Hungarian Justice Minister Laszlo Trocsanyi caused a stir recently by suggesting that Hungary could hardly help so many refugees, when it already has 800,000 Roma to integrate.

Some criminal gangs from the Roma clans of eastern Hungary stand accused of muscling in on the lucrative business of trafficking migrants from the Serbian border to Austria.

But most Roma are watching the current crisis from the sidelines.

In Budapest, a man begging outside the East Station claimed to be Syrian. "Don't believe him", shouted a woman from the doorway of a shop - "he's a local". For local, read Roma.

East station has now been re-Christened "the Middle East station", in popular parlance, because of the sheer number of Syrians and Iraqis around it.

And the "pan-global picnic" continues, on every platform.